Change in treatment preferences in pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures: a Danish nationwide register study of 36,244 fractures between 1997 and 2016

Rasmus T HANSEN 1, Nicolas W BORGHEGN 1, Per Hviid GUNDTOFT 1,2, Katrine A NIELSEN 3, Andreas BALSLEV-CLAUSEN 4, and Bjarke VIBERG 1,5

1 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Lillebaelt Hospital Kolding, University Hospital of Southern Denmark; 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Aarhus University Hospital; 3 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Zealand University Hospital; 4 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Hvidovre Hospital; 5 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark

Background and purpose — The choice between invasive and non-invasive treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures in children can be difficult. We investigated the trends in choice of treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures over a 20-year period.

Patients and methods — This is a population-based register study with data from 1997 to 2016 retrieved from the Danish National Patient Registry. The primary outcome was choice of primary treatment within 1 week divided into non-invasive treatment (casting only or closed reduction including casting) and invasive (Kirshner wires, intramedullary nailing [IMN], and open reduction internal fixation [ORIF]). The secondary outcomes were further sub-analyses on invasive treatment and age groups.

Results — 36,244 diaphyseal forearm fractures were investigated, yielding a mean incidence of 172 per 105/year. The proportion of fractures treated invasively increased from 1997 to 2016, from 4% to 23%. The use of Kirschner wires increased from 1% to 9%, IMN increased from 1% to 14%, and ORIF decreased from 2% to 1%. The changes were evident in all age groups but smaller in the 0–3-year age group.

Conclusion — We found an increase in invasive treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures over the investigated period. A change in invasive methods was also found, as the rate of IMN increased over the investigated period and became the predominant surgical treatment choice.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2023; 94: 32–37. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2023.7132.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Submitted: 2022-05-06. Accepted: 2022-12-17. Published: 2023-02-01.

Correspondence: bjarke.viberg@rsyd.dk

All authors stood for conceptualization while BV and PG stood for methodology and formal analyses. RTH and NWB wrote the original draft and all authors performed review and editing. Acquisition of funding for the fracture cohort was BV.

Handling co-editors: Ivan Hvid

Acta thanks Vera Halvorsen and Klaus Parsch for help with peer review of this study.

Fractures during childhood are common (1), with forearm fractures being the most frequent type, accounting for 36%–41% of all childhood fractures (2,3). Diaphyseal forearm fractures comprise 6% of pediatric fractures (3) and have limited remodeling potential compared with distal forearm fractures (4). Diaphyseal forearm fractures are therefore more difficult to manage and present a risk of complications and sequelae (5,6).

The choice of treatment in children with diaphyseal forearm fractures depends on several factors, including age, the type of fracture, and the angle of displacement (7). The gold standard in the treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures has been closed reduction and casting (7). Studies suggest that there is a trend toward managing these fractures invasively, especially with flexible intramedullary nailing (IMN) (8), which was first introduced in the late 1970s and 1980s (9-12). The role of surgery in diaphyseal forearm fractures remains a topic of debate (13), and indications for surgery vary across studies (14). A study conducted in the United States demonstrated a divergence between practice and research for managing forearm fractures, revealing that most of the reviewed research does not support the tendency toward more aggressive treatment (15). Therefore, it is important to be aware of the indications for surgery when treating forearm fractures in children.

We investigated the trends in choice of treatment in pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures over a 20-year period, with a secondary aim of examining these trends in different pediatric age groups.

Patients and methods

Study design

This is a population-based cohort study of children between 0 and 15 years of age treated for a diaphyseal ulna and/or radius fracture. Data from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2016, was retrieved from the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) (16). The study is reported according to the RECORD guidelines (17).

Setting and data source

The population of Denmark is approximately 5.8 million (18). Every person in Denmark is provided with a personal identification number (PIN; Central Person Register number) (19). The Danish Healthcare Department offers free healthcare to everyone with a Danish PIN. The PIN is used in medical records and administrative databases and is linked to many registers in Denmark, providing a unique source for data acquisition (20).

The DNPR contains data from public and private hospitals nationwide since 1977 for admitted patients and since 1995 for patients receiving outpatient treatment. DNPR is linked to the Danish Central Person Register. All ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes are registered longitudinally with time and date with a 99.7% degree of completeness (16). The positive predictive value of a correct primary diagnosis in orthopedic surgery is 83% (16), but the specific rate has not been investigated in diagnostics of fractures.

Participants

All patients with fractures are initially treated in the emergency department (ED) and thereafter admitted if surgery is needed. All fractures when diagnosed are given a specific ICD-10 diagnosis code (21), the use of which is mandatory in every hospital in Denmark. If the fracture is treated in the operating theater (OT), a specific procedure code is assigned using a code from the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) (22). The diagnosis and procedure codes are then transferred to the DNPR.

We used the ICD-10 diagnosis codes for diaphyseal ulna fracture (DS522), diaphyseal radius fracture (DS523), and diaphyseal fracture of both the ulna and radius (DS524) to find eligible patients. All patients from 0 to 15 years of age who were diagnosed with a diaphyseal forearm fracture were included in the study.

Variables

The primary outcome is the choice of primary treatment, set to be within 1 week, throughout the investigated period, divided into non-invasive and invasive treatment. The secondary outcomes are further sub-analyses on choice of invasive treatment including closed reduction and analyzing choice of treatment according to age group.

Non-invasive treatment was defined as:

- Casting only: No procedure code for surgery within 1 week of fracture diagnosis or NOMESCO codes for immobilization and bandaging of extremity or immobilization of upper extremity with a circular bandage (BLPC2)

- Closed reduction and casting: NOMESCO codes for diaphyseal ulna reduction (KNCJ01), diaphyseal radius reduction (KNCJ04), and reduction of both diaphyseal ulna and radius (KNCJ06). The setup in Denmark rarely provides the means of sedation in the ED; therefore, closed reduction and casting is performed in the OT.

Invasive treatment was defined as having 1 of the following treatments within 1 week of fracture diagnosis (DS522, DS523, and DS524):

- Kirschner wires: NOMESCO codes involving Kirschner wires for diaphyseal ulna (KNCJ41), diaphyseal radius (KNCJ44), and both diaphyseal ulna and radius (KNCJ 46).

- IMN: NOMESCO codes for IMN of the diaphyseal ulna (KNCJ51), diaphyseal radius (KNCJ54), and both diaphyseal ulna and radius (KNCJ56).

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF): NOMESCO codes for plating diaphyseal ulna (KNCJ61), diaphyseal radius (KNCJ64), and both diaphyseal ulna and radius (KNCJ66).

Age groups were determined by the author group before analyses were conducted. The 4-year intervals provide a good representation of pediatric growth development during infancy (0–3 years), early childhood (4–7 years), late childhood (8–11 years), and adolescence (12–15 years).

Bias

Invasive treatment with IMN is a merge of multiple procedure codes, one of which covers treatment with Kirschner wires. Because Kirschner wires do not have a large role in the treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures (23), it is likely that most of these procedures are actually intramedullary treatments with the wire fastened cortically on both sides, or maybe due to the unavailability of an IMN in the preferred diameter a Kirschner wire is used instead. Another reason for the inclusion of fractures treated with Kirschner wires is that it could be that the fractures are incorrectly coded as diaphyseal fractures instead of distal fractures. Notably, it can be difficult to distinguish between distal forearm fractures and diaphyseal forearm fractures in ICD-10 coding. Therefore, we decided to keep fractures treated with Kirschner wires in the invasive group.

Statistics

STATA 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used to achieve descriptive statistics of the number of cases. The incidence of fractures was calculated using the background population at the given time extracted from Statistics Denmark (24).

Ethics, funding, data sharing, and disclosures

The authors of this study had full access to all data and, due to Danish legislation, the authors are not able to share the raw data but can by request provide further data. We received funding from the Research Council of Hospital Lillebaelt to establish a large fracture cohort but not directly for this study. There are no conflicts of interest related to this study. BV has, outside the study, received payment for lectures from Zimmer Biomet and Osmedic Swemac. Completed disclosure forms for this article following the ICMJE template are available on the article page doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.7132

Results

36,244 diaphyseal forearm fractures diagnosed from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2016, were included (Table 1). Thus, the mean fracture incidence was 172/105/year over the 20-year period. Of the 36,244 fractures, 5,221 (14%) were only in the ulna, 11,006 (30%) were only in the radius, and 20,017 (55%) were in both the ulna and the radius. A total of 27,224 fractures (75%) were treated with casting only, 4,846 (13%) with closed reduction and casting, 1,487 (4%) with Kirschner wires, 3,690 (10%) with IMN, and 484 (1%) with ORIF (Table, see Appendix).

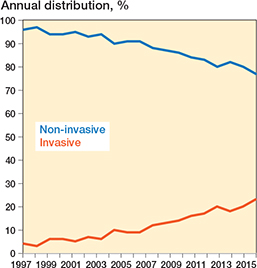

The tendency in the choice between non-invasive and invasive treatment changed over the investigated period, with the rate of invasive treatment increasing from 4% to 23% and the non-invasive thus decreasing from 96% to 77% between 1997 and 2016 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-invasive vs. invasive treatment choice over a 20-year period in Denmark

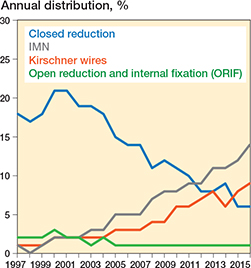

Between 1997 and 2016, the use of casting alone decreased from 78% to 70% while closed reduction and casting decreased from 18% to 6% (Table, see Appendix). Kirschner wires were used in 1% in 1997 increasing to 9% in 2016. IMN increased, constituting 1% of the treated distal diaphyseal forearm fractures in 1997 and 14% in 2016. The treatments with ORIF decreased throughout the study period, from 2% to 1% (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chosen type of invasive procedure in comparison with closed reduction.

The number of fractures in each age group was 4,911 (14%) in the 0–3-year age group, 11,429 (32%) in the 4–7-year age group, 11,539 (32%) in the 8–11-year age group, and 8,365 (23%) in the 12–15-year age group (Table, see Appendix).

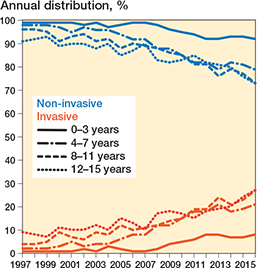

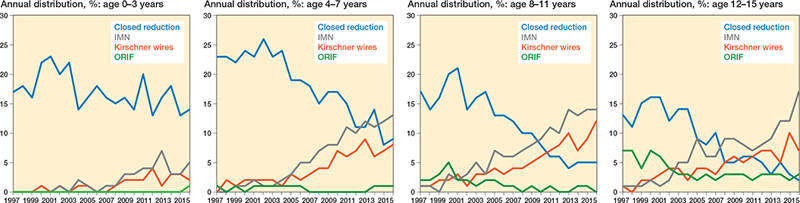

The trend in the choice between invasive and non-invasive treatment was consistent across all age groups, with invasive treatment increasing and non-invasive treatment decreasing. The largest changes were observed in the 8–11-year and 12–15-year age groups, while the smallest change was seen in the 0–3-year age group (Figure 3). The increasing invasive methods showed the same tendency in all 4 age groups as in the entire cohort, with a decrease in closed reduction and ORIF and an increase in IMN and Kirschner wires (Figure 4). The largest changes in invasive treatment were in the 8–11-year and 12–15-year age groups and the smallest change was seen in the 0–3-year age group.

Figure 3. Invasive in comparison with non-invasive method depending on age group over time.

Figure 4. Choice of invasive methods in comparison with closed reduction depending on age group over time.

Discussion

Our study showed an increase in invasive treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures throughout the investigated period. A change in invasive methods also appeared, with an over 15-fold increase in the use of IMN procedures over a 20-year period in Denmark, as well as a decrease in treatment with ORIF. We also found a decrease in the use of closed reduction and casting to less than half the number of cases per year during the study period. The same trends were found in all age groups throughout the investigated period, although the changes were small in the 0–3-year age group.

Other studies have found the same tendency (25). Although the results show a change in trends in invasive management of diaphyseal forearm fractures in children, the reason for this change is unclear. There is currently no nationwide guideline in Denmark on indications for invasive treatment of children’s diaphyseal forearm fractures. It is possible that the indications on which surgeons act have changed during the investigated period, emphasizing the need for generally accepted guidelines on this topic. We have not investigated patient records or radiographs and therefore do not know whether more complicated fractures (i.e., severe dislocated, angulated, or rotated fractures) occurred during the period that could have been treated invasively (26). It is possible that more complicated fractures have occurred, as a study suggested a correlation between a society with more screen time, more obesity in children, and a childhood culture with more extreme activities like trampoline and skating and complicated fractures (27).

This raises the question of whether the observed development with more surgery is beneficial. The objective of both invasive and non-invasive treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures should be to obtain the best functional outcome. Invasive surgery should be used when satisfactory anatomical reduction is not possible with non-surgical treatment, as it has been reported to reduce the complication of malunion by 50% compared with non-invasive treatment when managing diaphyseal forearm fractures (28). When treated non-invasively with closed reduction and casting, the risk of malunion has been reported to be up to 32% (29). Sinikumpu et al. (28) found that a third of the patients in their study had reoperations and unplanned reoperation was 2.6-fold more likely in the non-invasive group compared with the invasive, and deduced that this might be one of the explanations for the increased interest in surgical intervention with elastic stable IMN.

However, invasive treatment is not without risks. Reported complications after surgery for pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures include wound infection, hypoesthesia in the dorsal branch of the radial nerve, complaints during physical activities, malunion, osteomyelitis, and refracture (26,30,31). Antabak et al. (31) suggested that the complications are primarily due to improper choice of hardware and insertion technique.

Given these risks, why did we see an increase in invasive treatment, including a decrease in closed reduction, in our study? The increase of invasive treatment came in conjunction with the introduction of elastic stable IMN in Denmark, and we believe that it is more likely for the surgeon to choose IMN, a relatively uncomplicated surgery, over closed reduction and casting. From the surgeon’s point of view, it is better to choose elastic IMN, which is less invasive than ORIF, than risk the uncertainty of re-dislocation and yet another anesthesia for the child and parents after closed reduction and casting. We suggest that the tendency to use elastic IMN more and closed reduction with casting less results in a loss of skill and routine required to apply a satisfactory and clinically good cast. Being able to mold a good cast is an important skillset and can be supported by clinical tools such as the cast index, which can help predict redisplacement (32). Without proper training, closed reduction and casting can be an uncomfortable choice for the surgeon; this could affect the choice of treatment.

Limitations

A national database register study such as ours confers a risk of coding misclassification. This misclassification could be especially problematic if it changes over the 20-year period. Furthermore, it was not possible to extract detailed data regarding fracture classification (angulation, displacement, open, etc.) or investigate details concerning patient characteristics (sex, etc.), which limited our ability to acknowledge any patterns in terms of indication for surgery. Further, our study did not explore follow-up information on patient outcomes, making it difficult to suggest any benefits or disadvantages of the trends identified.

Conclusion

Our study showed an increase in invasive vs. non-invasive treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures over the investigated period. We also found a change in invasive methods used over the studied period: IMN increased and became the predominant choice of invasive treatment, whereas ORIF declined. Closed reduction with casting and immobilization decreased throughout the period.

This trend seems not to be based on sound evidence but more on the introduction of elastic IMN.

In the future, it is important to focus on the more evidence-based introduction of new treatment procedures.

- Cooper C, Dennison E M, Leufkens H G, Bishop N, van Staa T P. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19(12): 1976-81. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040902

- Lyons R A, Delahunty A M, Kraus D, Heaven M, McCabe M, Allen H, et al. Children’s fractures: a population based study. Inj Prev 1999; 5(2): 129-32. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.2.129.

- Rennie L, Court-Brown C M, Mok J Y, Beattie T F. The epidemiology of fractures in children. Injury 2007; 38(8): 913-22. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.01.036.

- Johari A N, Sinha M. Remodeling of forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 1999; 8(2): 84-7.

- Garg N K, Ballal M S, Malek I A, Webster R A, Bruce C E. Use of elastic stable intramedullary nailing for treating unstable forearm fractures in children. J Trauma 2008; 65(1): 109-15. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181623309.

- Landin L A. Epidemiology of children’s fractures. J Pediatr Orthop B 1997; 6(2): 79-83. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199704000-00002.

- Sinikumpu J J, Serlo W. The shaft fractures of the radius and ulna in children: current concepts. J Pediatr Orthop B 2015; 24(3): 200-6. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000162.

- Poutoglidou F, Metaxiotis D, Kazas C, Alvanos D, Mpeletsiotis A. Flexible intramedullary nailing in the treatment of forearm fractures in children and adolescents, a systematic review. J Orthop 2020; 20: 125-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.01.002.

- Lascombes P, Prevot J, Ligier J N, Metaizeau J P, Poncelet T. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing in forearm shaft fractures in children: 85 cases. J Pediatr Orthop 1990; 10(2): 167-71.

- Perez Sicilia J E, Morote Jurado J L, Corbacho Girones J M, Hernandez Cabrera J A, Gonzalez Buendia R. Ostéosyntesis percutanea en fracturas diafisarias de antebrazo en ninos y adolescents. Rev Esp Cir Osteoart 1977; 12: 321-34.

- Métaizeau J P. Ostéosynthèse chez l’enfant par embrochage centromédullaire élastique stable. Montpellier: Sauramps; 1988.

- Verstreken L, Delronge G, Lamoureux J. Shaft forearm fractures in children: intramedullary nailing with immediate motion: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8(4): 450-3. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198807000-00013.

- Flynn J M. Pediatric forearm fractures: decision making, surgical techniques, and complications. Instr Course Lect 2002; 51: 355-60.

- Wilkins K E. Operative management of children’s fractures: is it a sign of impetuousness or do the children really benefit? J Pediatr Orthop 1998; 18(1): 1-3.

- Eismann E A, Little K J, Kunkel S T, Cornwall R. Clinical research fails to support more aggressive management of pediatric upper extremity fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(15): 1345-50. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00764.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt S A, Sandegaard J L, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen H T. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015; 7: 449-90. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125.

- Nicholls S G, Quach P, von Elm E, Guttmann A, Moher D, Petersen I, et al. The REporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) Statement: methods for arriving at consensus and developing reporting guidelines. PLoS One 2015;10(5): e0125620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125620.

- Befolkningstal 2021 [Population in Denmark]. Available from: https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/emner/borgere/befolkning/befolkningstal.

- Bekendtgørelse af lov om Det Centrale Personregister 2020 [The Danish civil registration legislation]. Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2020/1297.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen H T. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014; 29(8): 541-9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm.

- NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures, 2010. Available from: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:970547/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Vopat M L, Kane P M, Christino M A, Truntzer J, McClure P, Katarincic J, et al. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures in children. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2014; 6(2): 5325. doi: 10.4081/or.2014.5325.

- Statestik D. FOLK2: Folketal 1. januar efter køn, alder, herkomst, oprindelsesland og statsborgerskab 2021 [Population by gender, age, country of origin and citizenship]. Available from: https://www.statistikbanken.dk/folk2?fbclid=IwAR0DmQMvYugUyCEVn4ipFR3COsGvnhCpcUC bhwg7SKG2qcs2c0p6rVxe4og.

- Cruz A I Jr, Kleiner J E, DeFroda S F, Gil J A, Daniels A H, Eberson C P. Increasing rates of surgical treatment for paediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures: a national database study from 2000 to 2012. J Child Orthop 2017; 11(3): 201-9. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.11.170017.

- Caruso G, Caldari E, Sturla F D, Caldaria A, Re DL, Pagetti P, et al. Management of pediatric forearm fractures: what is the best therapeutic choice? A narrative review of the literature. Musculoskelet Surg 2021; 105(3): 225-34. doi: 10.1007/s12306-020-00684-6.

- Sinikumpu J J. Too many unanswered questions in children’s forearm shaft fractures: high-standard epidemiological and clinical research in pediatric trauma is warranted. Scand J Surg 2015; 104(3): 137-8. doi: 10.1177/1457496915594285.

- Sinikumpu J J, Lautamo A, Pokka T, Serlo W. Complications and radiographic outcome of children’s both-bone diaphyseal forearm fractures after invasive and non-invasive treatment. Injury 2013; 44(4): 431-6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.032.

- Alrashedan B S, Jawadi A H, Alsayegh S O, Alshugair I F, Alblaihi M, Jawadi T A, et al. Outcome of diaphyseal pediatric forearm fractures following non-surgical treatment in a level I trauma center. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2018; 12(5): 60-5. PMID: 30202409.

- Kang S N, Mangwani J, Ramachandran M, Paterson J M, Barry M. Elastic intramedullary nailing of paediatric fractures of the forearm: a decade of experience in a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(2): 262-5. doi: 10.1302/0301620X.93B2.24882.

- Antabak A, Luetic T, Ivo S, Karlo R, Cavar S, Bogovic M, et al. Treatment outcomes of both-bone diaphyseal paediatric forearm fractures. Injury 2013; 44(Suppl. 3): S11-5. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(13)70190-6.

- McQuinn A G, Jaarsma R L. Risk factors for redisplacement of pediatric distal forearm and distal radius fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32(7): 687-92. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31824b7525.

Appendix

| Factor | Total | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 |

| Fracture incidence per 105 | – | 154 | 168 | 163 | 151 | 142 | 168 | 161 | 149 | 159 | 173 |

| Total fractures | 36,244 | 1,531 | 1,689 | 1,660 | 1,561 | 1,494 | 1,791 | 1,728 | 1,611 | 1,722 | 1,873 |

| Ulna shaft | 5,221 (14) | 217 (14) | 260 (15) | 256 (15) | 264 (17) | 232 (16) | 246 (14) | 240 (14) | 233 (14) | 251 (15) | 290 (15) |

| Radial shaft | 11,006 (30) | 351 (23) | 442 (26) | 388 (23) | 383 (25) | 362 (24) | 471 (26) | 442 (26) | 435 (27) | 485 (28) | 609 (33) |

| Ulna and radial s. | 20,017 (55) | 963 (63) | 987 (58) | 914 (59) | 1,016 (61) | 900 (60) | 1,074 (60) | 1,046 (61) | 943 (59) | 986 (57) | 974 (52) |

| Non-invasive | 32,070 (88) | 1,472 (96) | 1,624 (96) | 1,602 (97) | 1,463 (94) | 1,404 (94) | 1,699 (95) | 1,613 (93) | 1,508 (94) | 1,558 (90) | 1,706 (91) |

| Casting only | 27,224 (75) | 1,193 (78) | 1,339 (79) | 1,303 (78) | 1,139 (73) | 1,086 (73) | 1,363 (76) | 1,288 (75) | 1,221 (76) | 1,308 (76) | 1,439 (77) |

| Closed reduction | 4,846 (13) | 279 (18) | 285 (17) | 299 (18) | 324 (21) | 318 (21) | 336 (19) | 325 (19) | 287 (18) | 250 (15) | 267 (14) |

| Invasive | 4,174 (12) | 59 (4) | 65 (4) | 58 (3) | 98 (6) | 90 (6) | 92 (5) | 115 (7) | 103 (6) | 164 (10) | 167 (9) |

| Kirschner wire | 1,487 (4) | 12 (1) | 17 (1) | 18 (1) | 29 (2) | 32 (2) | 33 (2) | 40 (2) | 29 (2) | 55 (3) | 52 (3) |

| IMN | 3,690 (10) | 11 (1) | 7 (0) | 11 (1) | 24 (2) | 23 (2) | 31 (2) | 54 (3) | 49 (3) | 89 (5) | 93 (5) |

| ORIF | 484 (1) | 36 (2) | 41 (2) | 29 (2) | 45 (3) | 35 (2) | 28 (2) | 21 (1) | 25 (2) | 20 (1) | 22 (1) |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 0–3 years | 4,911 (14) | 275 (18) | 257 (15) | 259 (16) | 247 (16) | 239 (16) | 288 (16) | 269 (16) | 256 (16) | 232 (13) | 268 (14) |

| 4–7 years | 11,429 (32) | 487 (32) | 553 (33) | 595 (36) | 533 (34) | 495 (33) | 595 (33) | 577 (33) | 497 (31) | 559 (32) | 576 (31) |

| 8–11 years | 11,539 (32) | 433 (28) | 506 (30) | 503 (30) | 454 (29) | 444 (30) | 511 (29) | 519 (30) | 484 (30) | 539 (31) | 569 (30) |

| 12–15 years | 8,365 (23) | 336 (22) | 373 (22) | 303 (18) | 327 (21) | 316 (21) | 397 (22) | 363 (22) | 374 (23) | 392 (23) | 460 (25) |

| Factor | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Fracture incidence per 105 | 188 | 191 | 188 | 176 | 187 | 187 | 181 | 194 | 184 | 176 | |

| Total fractures | 2,030 | 2,059 | 2,026 | 1,887 | 1,994 | 1,973 | 1,892 | 2,009 | 1,898 | 1,816 | |

| Ulna shaft | 316 (16) | 316 (15) | 290 (14) | 241 (13) | 284 (14) | 281 (14) | 244 (13) | 266 (13) | 251 (13) | 243 (13) | |

| Radial shaft | 723 (36) | 730 (35) | 691 (36) | 680 (36) | 685 (34) | 665 (34) | 626 (33) | 694 (35) | 627 (33) | 517 (28) | |

| Ulna and radial shaft | 991 (49) | 1,013 (49) | 1,045 (52) | 966 (51) | 1,025 (51) | 1,027 (52) | 1,022 (54) | 1,049 (52) | 1,020 (54) | 1,056 (58) | |

| Non-invasive | 1,853 (91) | 1,817 (88) | 1,760 (87) | 1,618 (86) | 1,675 (84) | 1,635 (83) | 1,514 (80) | 1,645 (82) | 1,510 (80) | 1,394 (77) | |

| Casting only | 1,577 (78) | 1,588 (77) | 1,520 (75) | 1,414 (75) | 1,469 (74) | 1,480 (75) | 1,368 (72) | 1,462 (73) | 1,389 (73) | 1 ,278 (70) | |

| Closed reduction | 276 (14) | 229 (11) | 240 (12) | 204 (11) | 206 (10) | 155 (8) | 146 (8) | 183 (9) | 121 (6) | 116 (6) | |

| Invasive | 177 (9) | 242 (12) | 266 (13) | 269 (14) | 319 (16) | 338 (17) | 378 (20) | 364 (18) | 388 (20) | 422 (23) | |

| Kirschner wire | 59 (3) | 79 (4) | 91 (4) | 104 (6) | 122 (6) | 145 (7) | 147 (8) | 118 (6) | 148 (8) | 157 (9) | |

| IMN | 101 (5) | 141 (7) | 153 (8) | 148 (8) | 182 (9) | 177 (9) | 213 (11) | 224 (11) | 224 (12) | 248 (14) | |

| ORIF | 17 (1) | 22 (1) | 22 (1) | 17 (1) | 15 (1) | 16 (1) | 18 (1) | 22 (1) | 16 (1) | 17 (1) | |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 0–3 years | 268 (13) | 252 (12) | 273 (13) | 229 (12) | 254 (13) | 242 (12) | 214 (11) | 206 (10) | 207 (11) | 176 (10) | |

| 4–7 years | 608 (30) | 643 (31) | 618 (31) | 557 (30) | 591 (30) | 587 (30) | 605 (32) | 649 (32) | 531 (28) | 573 (32) | |

| 8–11 years | 649 (32) | 678 (33) | 625 (31) | 630 (33) | 628 (31) | 656 (33) | 610 (32) | 686 (34) | 751 (40) | 664 (37) | |

| 12–15 years | 505 (25) | 486 (24) | 510 (25) | 471 (25) | 521 (26) | 488 (25) | 463 (24) | 468 (23) | 409 (22) | 403 (22) |