Decreasing incidence of knee arthroscopy in Sweden between 2002 and 2016: a nationwide register-based study

Lukas BERGLUND 1, Cecilia LIU 1, Johanna ADAMI 3, Mårten PALME 4, Abdul Rashid QURESHI 2, and Li FELLÄNDER-TSAI 1

1 Department of Clinical Science Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC), Division of Orthopaedics and Biotechnology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm; 2 Division of Renal Medicine, Karolinska Institutet and Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm; 3 Sophiahemmet University, Stockholm; 4 Department of Economics, Stockholm University, Sweden

Background and purpose — Several randomized trials have demonstrated the lack of effect of arthroscopic lavage as treatment for knee osteoarthritis (OA). These results have in turn resulted in a change in Swedish guidelines and reimbursement. We aimed to investigate the use of knee arthroscopies in Sweden between 2002 and 2016. Patient demographics, regional differences, and the magnitude of patients with knee OA undergoing knee arthroscopy were also analyzed.

Patients and methods — Trends in knee arthroscopy were investigated using the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register (SHDR) to conduct a nationwide register-based study including all adults (>18 years of age) undergoing any knee arthroscopy between 2002 and 2016.

Results — The total number of knee arthroscopies performed during the studied period was 241,055. The annual surgery rate declined in all age groups, for males and females as well as patients with knee OA. The incidence dropped from 247 to 155 per 105 inhabitants. Over 50% of arthroscopies were performed in metropolitan regions.

Conclusion — We showed a dramatic decline in knee arthroscopy. There is variability in the surgery rate between males and females and among the regions of Sweden.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2023; 94: 26–31. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2023.7131.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Submitted: 2022-02-26. Accepted: 2023-01-01. Published: 2023-01-25.

Correspondence: li.fellander-tsai@ki.se

LB, LFT, and JA designed the study. CL and TQ were responsible for the collection of the data. CL and TQ performed the statistical analysis in collaboration with LB. LB, CL, JA, MP, and LFT participated in the interpretation of data. LB, CL, and LFT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing, editing, and approving the final version of manuscript.

The authors thank Dr Alejandro I Marcano for excellent help with data handling.

Handling co-editors: Søren Overgaard and Philippe Wagner

Acta thanks Michael Krogsgaard and Jonas Thorlund for help with peer review of this study.

Several randomized controlled trials have shown that knee arthroscopy as a therapy for osteoarthritits (OA) did not yield better results than placebo in the form of sham surgery (1-4). This has caused a change in reimbursement regarding use of arthroscopic intervention of knee OA in many countries, including Sweden. The procedure was removed from Swedish National Guidelines in 2012 in accordance with the National Board of Health and Welfare (5).

After the publications by Moseley et al. and Kirkley et al. in 2002 and 2008, the number of arthroscopies undertaken for degenerative knee disease and traumatic meniscal tears in Finland and Sweden changed (1,3,6). In Sweden there was an initial increase during the first part of the 2000s with a peak in 2008 and a subsequent decline (6). Similar results can also be found in other countries (7,8), making it a global change.

Regarding cost and effect, the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden has estimated a cost reduction for avoiding arthroscopic lavage of OA knees to be approximately SEK 25 million per year (5). Although there have been continuous quality improvements in arthroscopic surgery and healthcare, surgical procedures, even though arthroscopic, are still not without risk of postoperative complications such as wound infection, hematoma, and deep vein thrombosis (10-13). Treatment of these types of diagnoses also contributes to indirect costs not included in the above-calculated cost reduction.

Our study investigated the incidence of knee arthroscopy in Sweden between 2002 and 2016 in the adult population, including patient demographics, diagnoses, and regional differences.

Patients and methods

This study is a nationwide population-based register study using data from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register (SHDR). The register has been reviewed and validated (14). The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare established the national register in 1964. The SHDR includes inpatient care since 1987 and outpatient appointments since 2001 with data on personal identification number, age, sex, domicile of the patient, length of hospital stay, primary and secondary diagnoses, and surgical procedures during the hospital stay (14). Annual population data between 2002 and 2016 was retrieved from Statistics Sweden (SCB) to calculate surgery rate (incidence per 105 inhabitants). The incidence of knee arthroscopy was based on the entire adult population.

All adult patients from 18 years of age were included. The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) was used to identify surgical procedures. Patients with an ICD-10 procedure code indicative of any knee arthroscopy surgery between 2002 and 2016 were included in the study (Table 1).

To analyze the rate of knee arthroscopy among OA patients, ICD-10 diagnosis codes M17.0–9 were used to identify patients with an underlying primary and secondary OA disease of the knee followed by knee arthroscopy.

The data has been sorted to match the 21 regions in Sweden to simplify comparison. The annual surgery rate for each region was assessed.

To give an overview of the difference in densely populated areas versus less densely populated areas, the 3 regions with the highest population density (population per square kilometer, PD) were compared with the 3 regions with the lowest PD. According to SCB population data, the 3 most densely populated regions in 2017 were: Region Stockholm (PD 348), Region Skåne (PD 121), and Västra Götalandsregionen (PD 70). The 3 least densely populated regions in 2017 were: Region Västerbotten (PD 5), Region Jämtland Härjedalen (PD 3), and Region Norrbotten (PD 3). They were grouped into 2 groups for comparison: metropolitan regions and rural regions. Data on the number of arthroscopies performed and incidence were compared for each year in the study period.

Outcomes

Primary outcome was the number of knee arthroscopy performed, both during hospitalization and in an ambulatory care setting, in Sweden.

Secondary outcome was the number of knee arthroscopy performed in patients with ICD-10 coding for knee OA.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for each year between 2002 and 2016 were produced using the statistical software SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA), and SAS 9.4 level 1 M7 (SAS, Campus Drive, Cary, NC, USA). The frequency of knee arthroscopies performed in Sweden is presented, as well as the surgery incidence, calculated per 105 inhabitants, sorted by region, sex, and the following age groups: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥ 70. Separate analysis has been carried out for OA patients and presented in the same categories as for the general study population.

Ethics, data sharing, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Ethical approval from the institutional review board was granted for the study (Ref nos 2013/581-31/5 and 2016/2251-32). Data sharing is possible through SHDR. The study was fully financed by research grants from Region Stockholm (ALF Re No 20170479, 20180462, and 20200305). The authors report no conflict of interest. Completed disclosure forms for this article following the ICMJE template are available on the article page doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.7131

Results

The total number of knee arthroscopies in Sweden reported to SHDR between 2002 and 2016 was 241,055, comprising 218,082 performed in an ambulatory setting and 22,973 performed as in-hospital care (Table 2). The absolute number of yearly knee arthroscopies in Sweden decreased by 29% during the study period. The incidence also decreased, going from 247 to 155 knee arthroscopies per 105 inhabitants during the study period. The mean age of the patients was 41 and remained steady during the study period (Table 2).

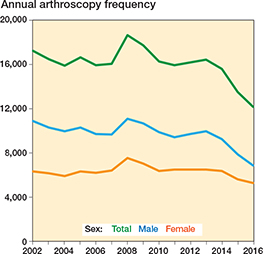

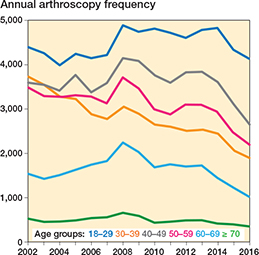

More men (60%) than women (40%) underwent knee arthroscopy with the difference slightly decreasing towards the end of the study period (Figure 1). The age group 18–29 years underwent most knee arthroscopies and the age group > 70 the least (Table 3). The incidence per 105 inhabitants decreased in all age groups. The biggest change was seen in the age groups 30–39 and 60–69, which both decreased by 50%. A peak was seen in all age groups in 2008 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Annual surgery frequency by sex.

Figure 2. Annual surgery frequency by age groups.

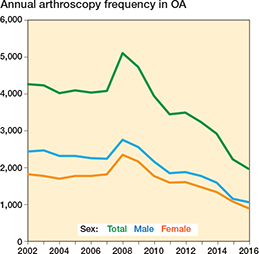

Figure 3. Annual surgery frequency in OA patients by sex.

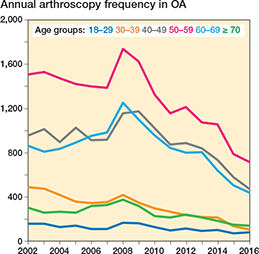

Figure 4. Annual surgery frequency in OA patients by age groups.

There was a big difference between the absolute number of knee arthroscopies in metropolitan regions and rural regions (Table 4). Over 50% of total knee arthroscopies were performed in a metropolitan region. The difference was at its peak during the beginning of the study period, 2002–2004, and was less evident during 2006–2009, only to increase again towards the end of the period. In total, 4,048 knee arthroscopies were excluded from this analysis as specific hospital data was missing. The mean value for all regions was 157 arthroscopies per 105 inhabitants. In the Capital Region of Stockholm, the mean incidence was 285. In general, there has been a decrease in all regions (Table 5, see Appendix).

The total number of knee arthroscopies performed on patients with knee OA has decreased since 2002 (Table 6). In 2002, 4,277 operations were done on OA indication and in 2016 the number had dropped to 1,970 operations. The maximum amount occurred in 2008 (n = 5,116). The incidence per 105 inhabitants has also decreased in this patient group. In 2002 it was 61, in comparison with 25 in 2016. More male patients with knee OA were treated with knee arthroscopy than females (Table 6). The difference decreased over time. The largest age group undergoing knee arthroscopy for OA diagnosis was 50–59 (Table 6).

Discussion

The main finding in this nationwide population-based register study is that the absolute number of knee arthroscopies performed each year in Sweden decreased between 2002 and 2016 even though the population as a whole increased. This includes all age groups, men and women, as well as patients with OA of the knee. The same change can also be seen in the incidence per 105 inhabitants. This does not mean that the total amount of knee surgeries in a broader sense has decreased. A study performed in Florida, USA, demonstrated that the rate of knee arthroscopies declined between 2002 and 2015 (15).

The Swedish National Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Diseases, published in 2012 (5), excluded arthroscopic lavage and debridement as treatment for OA, but the most cited studies on its ineffectiveness had already been published in 2002 and 2008 (1-4). Since then, there has been a consensus in Sweden that arthroscopic lavage and debridement should not be used for treating knee OA (16). The change of practice can be seen in the results, as patients in the older age groups are being operated on less frequently today. The arthroscopic surgery rate on patients with knee osteoarthritis decreased during the study period. Other studies have shown similar results up to 2012 (6) and it is noteworthy that there is a further decrease up to 2016. Evidence thus suggests that high-quality studies on the effectiveness of knee arthroscopy has, together with national guidelines, impacted healthcare on a global scale resulting in higher precision for the indication of knee arthroscopy, thus avoiding unnecessary complications. Taken together it is clear that change in practice requires time despite available evidence.

The mean age of patients undergoing knee arthroscopy has, in general, remained the same. Most of the patients are young, in the age group 18–29, and the change in incidence among them is small compared with the other groups. The result could speculatively be explained by the fact that these patients are treated with knee arthroscopy because of injuries occurring during sports or physical activity, with specific symptoms of knee injury compared with degenerative knee disorders. Recommendations regarding arthroscopic knee surgery for younger patient groups have remained the same although studies suggest that, even without OA, degenerative meniscus injuries may not be a future indication for surgery (9).

There was a notable increase in the number of arthroscopies performed from 2006 to 2008, followed by a rapid decrease. This reduction occurred before the guidelines were changed (in 2012). Despite the publication of studies on the ineffectiveness of arthroscopy as general treatment for OA in 2002 and 2008, the magnitude of the reduction in surgeries was considerable (Table 6). The reason for this rapid change is not clear. A connection between health, healthcare services, and macroeconomic conditions might play a role regarding behavior. A study in the United States by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons showed that the demand for joint reconstruction surgery and the visits to outpatient clinics decreased by around 30% following the 2008 economic crisis (17). It is possible that the 2008 financial crisis and the following recession also affected the availability and use of knee arthroscopy in Sweden. Even though some studies show higher utilization of healthcare in a recession, orthopedic surgery in general and knee arthroscopies in particular are not lifesaving and might follow a different pattern. Knee arthroscopies are usually done in ambulatory care. These clinics in Sweden, many of which are privately owned and operated, might have been affected in times of economic instability.

Furthermore, the arthroscopic surgery rate showed great variability between metropolitan and rural regions in Sweden. This reflection of inequality deserves to be pointed out as all regions share the same national reimbursement, healthcare policy, and legislation. The regional variations may reflect variations in surgeons’ opinions and beliefs concerning clinical indications for surgery, which has also been demonstrated for knee arthroplasty (18). Large regional differences have previously also been shown regarding arthroscopic meniscal procedures (19) and a recent publication demonstrated a large decrease in the incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures and other arthroscopic knee procedures from 2010 to 2018 (20).

Strengths and limitations

The size of the data set is one of the strengths of this nationwide population-based register study. Because our study is registerbased, it is not possible to know how OA was diagnosed. There is a possibility that the coding was influenced by other factors, such as physician habits, insurance policies, patients’ presentation, etc. As we included both minor and major surgical codes, we cannot rule out changes also in major procedures separate from minor procedures due to the emerging debate following several RCTs published in high-impact journals.

The division of metropolitan regions and rural regions was simplified, as we studied only regions and not specific cities. The 3 largest cities in Sweden are Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö, and they are considered as metropolitan areas (regions). However, the regions they are included in also cover a large number of smaller cities and rural areas. The difference in arthroscopy rate between the regions is suspected to be even larger if a finer analysis were to be made.

Conclusion

The incidence of knee arthroscopy in Sweden has declined in all age groups, for both male and female patients as well as patients with knee OA. There were considerable regional variations in the incidence of knee arthroscopy. Living in a densely populated area seems to increase the possibility of being treated with a knee arthroscopy.

- Moseley J B, O’Malley K, Petersen N J, Menke T J, Brody B A, Kuykendall D H, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002; 347(2): 81-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013259.

- Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan J P, Jamali A, Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(11): 994-1000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01618.

- Kirkley A, Birmingham T B, Litchfield R B, Giffin J R, Willits K R, Wong C J, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(11): 1097-107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708333.

- Herrlin S V, Wange P O, Lapidus G, Hållander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(2): 358-64. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för rörelseorganens sjukdomar 2012 Osteoporos, artros, inflammatorisk ryggsjukdom och ankyloserande spondylit, psoriasisartrit och reumatoid artrit. Stöd för styrning och ledning. 2012. ISBN 978-91-87169-32-8. Artikelnr 2012-5-1.

- Mattila V M, Sihvonen R, Paloneva J, Felländer-Tsai L. Changes in rates of arthroscopy due to degenerative knee disease and traumatic meniscal tears in Finland and Sweden. Acta Orthop 2016; 87(1): 5-11. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2015.1066209.

- Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (1): CD005118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005118.pub2.

- Harris I A, Madan N S, Naylor J M, Chong S, Mittal R, Jalaludin B B. Trends in knee arthroscopy and subsequent arthroplasty in an Australian population: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 14(1): 143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-143.

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(26): 2515-24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189.

- Ilahi O A, Reddy J, Ahmad I. Deep venous thrombosis after knee arthroscopy: a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy 2005; 21(6): 727-30. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.03.007.

- van Adrichem R A, Nelissen R G H H, Schipper I B, Rosendaal F R, Cannegieter S C. Risk of venous thrombosis after arthroscopy of the knee: results from a large population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost 2015; 13(8): 1441-8. doi: 10.1111/jth.12996.

- Abram S G F, Judge A, Beard D J, Price A J. Adverse outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a study of 700 000 procedures in the national Hospital Episode Statistics database for England. Lancet 2018; 17; 392(10160): 2194-202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31771-9.

- Friberger Pajalic K, Turkiewicz A, Englund M. Update on the risks of complications after knee arthroscopy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018; 19(91): 179. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2102-y.

- Ludvigsson J F, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim J, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11(1): 450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450.

- Howard D H. Trends in the use of knee arthroscopy in adults. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(11): 1557-8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4175.

- Roos H, Karlsson J, Svensson O, Engebretsen L, Renström P, Dahlberg L. Arthroscopy in knee osteoarthritis is one thing: surgery of the menisci another. Läkartidningen 2008; 105(42): 2950-1.

- Iorio R, Davis III C M, Healy W L, Fehring T K, O’Connor M I, York S. Impact of the economic downturn on adult reconstruction surgery: a survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(7): 1005-14. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.08.009.

- Troelsen A, Schroder H, Husted H. Opinions among Danish knee surgeons about indications to perform total knee replacement showed considerable variation. Dan Med J 2012; 59(8): A4490.

- Hare K B, Vinther J H, Lohmander L S, Thorlund J B. Large regional differences in incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures in the public and private sector in Denmark. BMJ Open 2015; 5(2): e006659. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006659.

- Lundberg M, Søndergaard J, Viberg B, Lohmander S L, Thorlund J B. Declining trends in arthroscopic meniscus surgery and other arthroscopic knee procedures in Denmark: a nationwide register-based study. Acta Orthop 2022; 93: 783-93. doi: 10.2340/17453674.2022.4803.