Direct anterior and direct lateral approach in patients with femoral neck fractures receiving a total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial

John Magne HOSETH 1,2, Tommy Frøseth AAE 1,3,4, Øystein Bjerkestrand LIAN 1,3, Tor Åge MYKLEBUST 4,5, and Otto Schnell HUSBY 1,3

1 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Health Møre and Romsdal HF, Kristiansund Hospital, Kristiansund; 2 Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU, Trondheim; 3 Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, NTNU, Trondheim; 4 The Clinical Research Unit, Health Møre and Romsdal HF, Ålesund; 5 The Cancer Registry of Norway, Oslo, Norway

Background and purpose — The optimal approach to the hip joint in patients with displaced femoral neck fractures (dFNF) receiving a total hip arthroplasty (THA) remains controversial. We compared the direct lateral approach (DLA) with the direct anterior approach (DAA) primarily on Timed Up and Go (TUG), and secondarily on the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS), the Oxford Hip Score (OHS), EQ5D-5L, and the EQ5D-VAS.

Methods — Between 2018 and 2023, we conducted a randomized controlled trial including elderly patients with dFNFs treated with THA. The primary outcome was the difference in TUG at 6 weeks postoperatively. Key secondary outcomes were TUG at 2, 12, and at 52 weeks postoperatively, and FJS, OHS, EQ5D-5L, and EQ5D-VAS at 2, 6, 12, and at 52 weeks postoperatively.

Results — 130 patients with a mean age of 78.6 (standard deviation 1.2) were allocated to DAA (n = 64) or DLA (n = 66). There was no statistically significant difference in TUG times at 6 weeks postoperatively between the DAA and the DLA, 16.0 s (95% confidence interval [CI] 13.2–18.7) vs 17.8 s (CI 15.1–20.4), estimated mean difference –1.8 s (CI –5.7 to 2.0). However, patients who underwent DAA had a significantly higher FJS at 2, 6, and 12 weeks.

Conclusion — Among elderly patients with dFNF we found no difference between DAA or DLA regarding crude mobility as demonstrated with the TUG test, but patients treated with DAA showed better outcomes in the FJS in the early post-fracture period though not at 52 weeks.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2025; 96: 73–79. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2025.42847.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing – Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Nordic Orthopedic Federation. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Submitted: 2024-09-17. Accepted: 2024-12-21. Published: 2025-01-13.

Correspondence: jmhoseth@gmail.com

JMH: original idea, interpretation of data, drafting and revision of manuscript. TFA: interpretation of data, revision of manuscript. OHU: interpretation of data, revision of manuscript. TÅM: statistical analysis, interpretation of data. ØBL: revision of manuscript.

Handling co-editors: Cecilia Rogmark and Robin Christensen

Acta thanks Inari Laaksonen and Olof Sköldenberg for help with peer review of this manuscript.

The optimal surgical access to the hip joint in patients with femoral neck fractures (FNF) has been debated for decades [1]. The direct lateral approach (DLA) or Hardinge approach is easy to learn and gives low dislocation rates in the older FNF population [2]. The disadvantage of the DLA is that failure of gluteus medius can occur, which may lead to Trendelenburg gait with varying degrees of limping and discomfort [3]. The direct anterior approach (DAA) utilizes an intermuscular and an interneural interval, avoiding detachment of any muscles that could give rise to joint instability and a pathological gait pattern [4]. However, the DAA is associated with a learning curve and perioperative complications such as fractures and early femoral stem loosening [5]. Several studies have compared the DAA with the DLA in patients receiving a total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to hip osteoarthritis (OA). The general conclusion is that both groups perform equally well in terms of function, but that the DAA group may have a more rapid rehabilitation immediately after surgery, but not after 3 months [6-8]. FNF patients are usually older than patients receiving a THA due to hip OA, and they often have serious comorbidities [9]. Swift postoperative mobilization and rehabilitation is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality in the FNF population [10], and the DAA may therefore prove advantageous in the crucial immediate postoperative period. Few studies have compared the DAA with the DLA in elderly patients with FNF treated with a THA. In this study we aimed to investigate whether the DAA has superior outcomes to the DLA in elderly patients with FNF treated with a THA.

Methods

Trial design

A prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted in Kristiansund Hospital, Norway from November 2018 to February 2023, comparing the DAA with the DLA in patients with displaced FNF (dFNF) receiving a THA [11] based on the functional outcomes. The study is in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines.

Participants

Patients above 50 years with a dFNF Garden type 3 or 4 were considered for inclusion if they were able to give written informed consent and were ambulatory before sustaining the fracture. The exclusion criteria were infection around the hip, alcohol use disorder, pathological fracture, bedridden patients, multitrauma patients, patients with life expectancy below 6 months (determined by consulting an internal medicine physician or an oncologist in case of advanced cancer disease), and patients with a known diagnosis of dementia or other causes of cognitive impairment. The presence or absence of exclusion criteria was determined through prior medical records, anamnesis, physical examination, and interview with next of kin. Exclusion criteria were set to minimize the loss to follow-up.

Intervention

The DAA group was compared with the DLA group in a 1:1 ratio. All patients were treated with a THA.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was to compare the Timed Up and Go (TUG) at 6 weeks postoperatively. TUG at 6 weeks was chosen because it measures crude mobilization at an early point in the rehabilitation [12]. Secondary outcomes were differences in the TUG at 2, 12, and 52 weeks postoperatively. Further secondary outcomes were differences in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), EQ5D-5L, and EQ5D-VAS postoperatively at 2, 6, 12, and 52 weeks. As the main focus of this article is the functional outcomes, the radiological results will be discussed in a separate article.

Sample size

Given the heterogeneity in FNF patients we did sample size calculations for TUG, FJS, and the OHS to ensure that the number of patients included would give sufficient power to find a significant difference. The sample size calculated for TUG is based on 2 previous studies [12,13]. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was set to 3.4 s, and the standard deviation (SD) at 6.9. With a power of 80%, and a level of significance of 5%, 52 patients were required for each group. For the FJS we get 36 patients in each group when we set the MCID to 10 and the SD to 15 [14]. For the OHS we get 52 patients in each group when we set the MCID to 5 points and the SD to 9 [15]. Due to the high 1-year mortality in this study population, we estimated a 20% loss to follow-up (8). Consequently, the sample size is 65 patients in each group, giving a total of 130 patients.

Randomization and stratification

Sequence generation and allocation. Stratification was performed to ensure equality among the groups. Stratification was based on 3 prognostic factors: (i) pre-fracture place of residence (i.e., home or residential care); (ii) pre-fracture functional status (i.e., using a walking aid or walking independently); (iii) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class (i.e., Class I/II or III/IV/V). Further, patients were assigned to either DAA or DLA using a web-based randomization program [16]. In addition to randomization, this program stores the data prior to analysis.

Implementation

The patients were included by the orthopedic resident on duty, while the principal investigator generated the allocation sequence and assigned patients to type of intervention.

Blinding

There was no blinding of patients, surgeon, or physiotherapist.

Surgery

2 experienced hip surgeons, both considered to be beyond the learning curve (> 100 procedures) for the DAA [17], performed all surgeries. The surgical procedure has already been described in detail in a recent study reporting exploratory results from the same study population [11].

Primary outcome

TUG is a validated and reliable mobility assessment tool and measures the time that a person takes to rise from a chair, walk 3 m, turn around, walk back to the chair, and sit down [18]. TUG has good validity, responsiveness, and clinical utility when applied as a discharge measure in patients hospitalized for hip fractures, because it measures the ability to ambulate independently [19]. We standardized the walking aid to a rollator [20]. Patients first performed a test round, followed by 2 rounds where the average time was calculated.

Secondary outcomes

The FJS measures the patient’s ability to forget about the joint replacement in everyday life. The FJS consists of 12 questions that are each answered on a 5-level scale, converted to a score that ranges from 0 (worst condition) to 100 points (best condition) [21]. The FJS has been validated in the hip joint fracture population [22]. The OHS is a validated questionnaire for patients undergoing THA for hip OA and FNF [23]. It consists of 12 items related to daily tasks directly influenced by poor hip function. The generic EQ5D-5L is a validated quality of life questionnaire consisting of 5 questions related to daily activities scored on a 5-point ordinal score scale [24]. As there is no Norwegian index, the EQ5D-5L was converted into a Swedish index score ranging from –0.314 (worst) to 1 (best). In EQ5D-VAS, respondents report their perceived health status with a grade ranging from 0 (worst possible health status) to 100 (best possible health status) [25].

The TUG and PROMs were administered by physiotherapists. In cases where transportation back and forth to the hospital for assessment was deemed too strenuous for patients, the study physiotherapists trained external physiotherapists in nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities in the study protocol to enable them to perform the testing.

Statistics

Demographics and clinical parameters were analyzed as descriptive statistics using mean and SD. To analyze differences in TUG, FJS, OHS, EQ5D-5L, and EQ5D-VAS over time, we estimated repeated measures mixed-effect models (RMMEM) with random intercepts for each patient to facilitate the longitudinal structure of the data. Separate models for each of the 5 outcomes were estimated, and all models included study group, time, and the interaction between study group and time as covariates. From the estimated models, we predicted marginal means, and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), for each combination of time and study group. Pairwise differences were assessed using the Wald test. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics, registration, data sharing, funding, use of AI, and disclosures

This randomized controlled trial obtained ethical approval from the Regional Ethics Committee in Norway (ID 2018/935). Written informed consent was obtained. The study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov with ID NCT03695497, Protocol ID 2018/935. Data sharing is possible upon request, which requires fulfillment of law regulations before distribution to foreign countries. No funding was required for this study. AI was not used. Complete disclosure of interest forms according to ICMJE are available on the article page, doi: 10.2340/17453674.2025.42847

Results

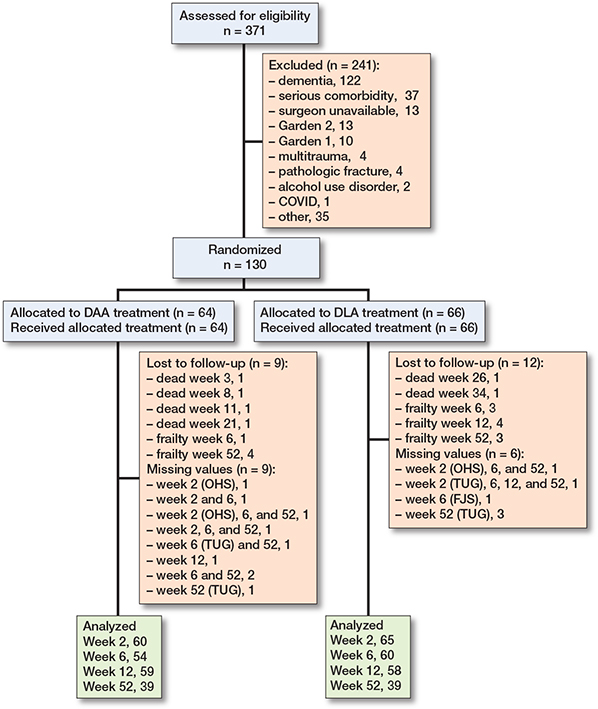

Of 371 screened patients, 130 patients were included and 64 assigned to the DAA and 66 to the DLA group, respectively (Figure 1). 6 died in the study period of 52 weeks (4 from DAA and 2 from DLA). In most instances, the reason why some patients dropped out or missed certain check-ups were because they found the study controls too cumbersome. Baseline characteristics of the 2 groups were similar (Table 1). The hip-related complications were dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, infection, and Trendelenburg gait (see Table 3).

Primary outcome

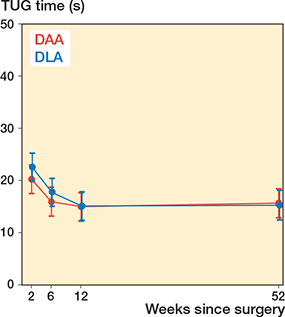

There was no statistically significant difference in TUG times at 6 weeks postoperatively between the DAA and the DLA, 16.0 s (CI 13.2–18.7) vs 17.8 s (CI 15.1–20.4), estimated mean difference –1.8 s (CI –5.7 to 2.0).

Secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference in TUG times between the groups at 2, 12, and 52 weeks post-fracture (Table 2). TUG time was unchanged in both groups from 12 to 52 weeks postoperatively (Figure 2). The TUG times at 52 weeks for DAA and DLA were 15.6 s (CI 12.9–18.4) vs 15.2 s (CI 12.4–18.0), estimated mean difference 0.4 s (CI –3.5 to 4.4).

| Factor | DAA (CI) | n | DLA (CI) | n | Difference (CI) |

| TUG (s) | |||||

| 2 weeks | 20.2 (17.5–23.0) | 62 | 22.6 (19.9–25.2) | 65 | –2.4 (–6.2 to 1.4) |

| 6 weeks | 16.0 (13.2–18.7) | 54 | 17.8 (15.1–20.4) | 61 | –1.8 (–5.7 to 2.0) |

| 12 weeks | 14.9 (12.2–17.7) | 59 | 15.1 (12.4–18.0) | 58 | –0.2 (–4.0 to 3.7) |

| 52 weeks | 15.6 (12.9–18.4) | 39 | 15.2 (12.4–18.0) | 39 | 0.4 (–3.5 to 4.4) |

| FJS | |||||

| 2 weeks | 52 (44–60) | 62 | 39 (32–47) | 66 | 13 (2 to 23) |

| 6 weeks | 62 (54–69) | 55 | 48 (40–55) | 60 | 14 (3 to 25) |

| 12 weeks | 70 (63–78) | 59 | 55 (48–63) | 58 | 15 (5 to 25) |

| 52 weeks | 76 (69–84) | 40 | 66 (58–73) | 42 | 10 (–0.1 to 21) |

| OHS | |||||

| 2 weeks | 29 (26–31) | 60 | 26 (24–28) | 65 | 3 (–0.2 to 6.0) |

| 6 weeks | 35 (33–38) | 55 | 31 (29–33) | 61 | 4 (1.2 to 7.3) |

| 12 weeks | 39 (37–41) | 59 | 36 (33–38) | 58 | 3 (0.1 to 6.2) |

| 52 weeks | 42 (40–44) | 40 | 38 (36–40) | 42 | 4 (0.4 to 7.0) |

| EQ5D-5L | |||||

| 2 weeks | 0.82 (0.78–0.87) | 62 | 0.78 (0.74–0.83) | 66 | 0.04 (–0.03 to 0.1) |

| 6 weeks | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) | 55 | 0.86 (0.82–0.91) | 61 | –0.02 (–0.1 to 0.05) |

| 12 weeks | 0.87 (0.82–0.91) | 59 | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | 58 | –0.00 (–0.1 to 0.1) |

| 52 weeks | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 40 | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) | 42 | 0.06 (–0.01 to 0.1) |

| EQ5D-VAS | |||||

| 2 weeks | 57 (52–62) | 62 | 62 (57–67) | 66 | –5 (–12 to 2) |

| 6 weeks | 64 (59–69) | 55 | 65 (60–70) | 61 | –0.7 (–8 to 7) |

| 12 weeks | 67 (62–72) | 59 | 68 (63–73) | 58 | –0.8 (–8 to 6) |

| 52 weeks | 69 (64–75) | 40 | 68 (63–73) | 42 | 1.0 (–6 to 9) |

| Baseline = 2 weeks after surgery. n = number of completed answers. For abbreviations, see Table 1 and the following: CI = 95% confidence interval; TUG = Timed Up and Go; FJS = Forgotten Joint Score; OHS = Oxford Hip Score; VAS = visual analogue scale. |

|||||

Figure 2. Least squares means for all time points by group for TUG, presenting 95% confidence interval for each group at different weeks following surgery.

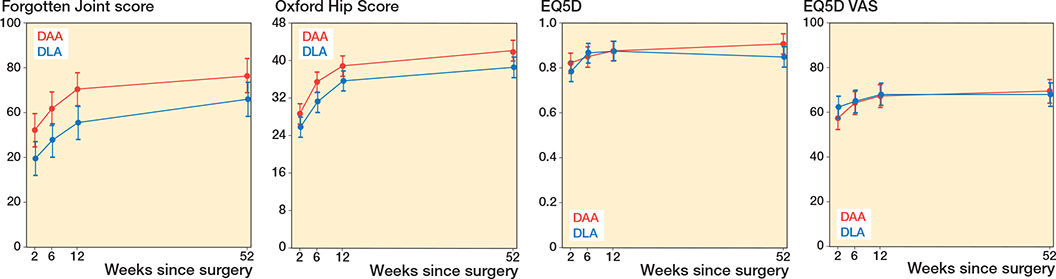

The FJS score was significantly higher for the DAA group at 2, 6, and 12 weeks postoperatively. The greatest difference was in week 12, 70 (CI 63–78) vs 55 (CI 48–63), estimated mean difference 15 (CI 5–25) (Table 2). The difference in week 6 was 62 (CI 54–69) vs 48 (CI 40–55), estimated mean difference 14 (CI 3–25). The difference at 52 weeks was 76 (CI 69–84) vs 66 (CI 58–73), estimated mean difference 10 (CI –0.1 to 21).

The OHS score was higher for the DAA group at week 6, 35 (CI 33–38) vs 31 (CI 29–33), estimated mean difference 4 (CI 1.2–7.3) (Table 2). The difference at 52 weeks was 42 (CI 40–44) vs 38 (CI 36–40), estimated mean difference 4 (CI 0.4–7). There was no difference in the EQ5D-5L and EQ5D-VAS between the groups at the 4 follow-up points (Table 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Least squares means for all time points by group for FJS, OHS, EQ5D-5L, and EQ5D-VAS, presenting 95% confidence interval for each group at different weeks following surgery.

Regarding destination of discharge, 40 (67%) patients were discharged to home in the DAA group, while this was the case for 33 (52%) patients in the DLA group.

Discussion

We aimed to compare functional outcome and PROMs after THA in patients with dFNF treated either with the DAA or the DLA. The most important finding in this study was that the 2 groups had similar mean values in TUG time at 6 weeks post-fracture, and there was no clinical difference between the groups. In contrast, the FJS demonstrated a clinically significant difference in favor of the DAA group in the early post-fracture period, up to 3 months.

We also found a minor difference in the OHS between the groups at 6 weeks post-fracture in favor of the DAA, but the effect size was less pronounced than for the FJS.

In the literature the MCID for FJS is found to be 8 points [14,26]. In our study the FJS difference is above the MCID at every timepoint, reflecting clinical significance. However, the MCID for OHS is set at 5 points [15], rendering our results not clinically significant as the greatest OHS difference in our study was 4 points. Although a difference between the DAA and DLA was detected for OHS at week 6, a correlation with EQ5D results could not be demonstrated. Although the EQ5D diverged between the 2 groups from 12 weeks, the difference did not reach statistical significance.

The TUG measures crude mobility, while the FJS focuses on awareness of the hip joint. Our results suggest that patients treated with the DLA may be more conscious of their hip joint than those with the DAA.

The reason for the discrepancy in TUG and PROMS could reflect a floor effect in TUG due to the initial difficulty of conducting the test in a post-fracture setting. Similar results were found in a study by Ugland et al., where they compared the DLA with the anterolateral approach (ALA) in a FNF population receiving a hemiprosthesis (HA) [27]. They could not demonstrate a difference in TUG at any time point post-fracture; however, they could demonstrate a high risk for a positive Trendelenburg test in the DLA group, similar to our findings (Table 3). Saxer et al. compared the DAA with the DLA in 190 patients with FNF receiving a HA [28]. They measured TUG at 3 weeks postoperatively. Corresponding to our results, they could not find a statistically significant difference in TUG between the groups, but they showed an advantage for DAA in a subgroup of patients with low pre-fracture functional independence.

Another study comparing the DLA with the ALA in patients with FNF receiving a THA found a clinically significant difference in TUG times at 3 months post-fracture in favor of ALA [29]. Further, they could also demonstrate a difference in OHS at 3 months post-fracture in favor of ALA, aligning with our results. Equivalent to our study, they also excluded patients with dementia.

In a study comparing DAA with ALA in patients with FNF receiving an HE, Bűcs et al. found a significantly better Harris Hip Score in the DAA group compared with the ALA group at 2 and 6 weeks post-fracture [30]. Another study by Langlois et al. compared the DAA with the posterior approach (PA) in a population of FNF patients treated with HA. They found better TUG times at 6 weeks postoperatively for the DAA than for the PA [31]. Further, the PA was associated with a higher dislocation rate compared with the DAA, 20% and 3%, respectively. This corresponds to our findings of a low dislocation rate in the DAA. The PA for FNF is associated with an increased dislocation rate in several high-quality studies, which renders it less suitable for the FNF population [32,33]. It appears that the DAA and the ALA could offer some advantages in the early post-fracture phase in the FNF population compared with the DLA and PA [27-33].

The relatively low 1-year mortality in our population of approximately 5% can be ascribed to the strict inclusion criteria, excluding patients with severe multimorbidity.

Limitations

One limitation is the fact that we have no pre-fracture status of our outcome measures, which would have been a valuable input in the RMMEM analysis. Another limitation is that our population is a selected group of patients with dFNF. We excluded one-third of the patients assessed for eligibility due to dementia, which are the patients at highest risk of dislocation. We also excluded patients with multimorbidity who were not expected to live beyond 6 months after inclusion. Our cohort is not entirely representative of the actual FNF population. Further, the lack of blinding is a potential source of bias, particularly for subjective outcome measures like the FJS and OHS. Another limitation is the number of missing values in both groups, although the RMMEM to some extent compensates for missing data. A noteworthy strength of this study is the randomized controlled design with careful stratification of certain prognostic factors, resulting in similar preoperative and demographic values between the groups.

Conclusion

We found no difference in functional outcome between the groups when TUG was used at different times postoperatively. There was a slight difference in favor of DAA in the OHS at 6 weeks post-fracture, but the difference did not reach clinical significance. Based on the FJS, the patients in the DAA group seemed to be less aware of their hip than those in the DLA group at the early time points after the fracture.

- Mjaaland K E, Kivle K, Svenningsen S, Nordsletten L. Do postoperative results differ in a randomized trial between a direct anterior and a direct lateral approach in THA? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019; 477(1): 145-55. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000439.

- Page B J, Parsons M S, Lee J H, Dennison J G, Hammonds K P, Brennan K L, et al. Surgical approach and dislocation risk after hemiarthroplasty in geriatric patients with femoral neck fracture with and without cognitive impairments: does cognitive impairment influence dislocation risk? J Orthop Trauma 2023; 37(9): 450-5. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000002614.

- Berstock J R, Blom A W, Beswick A D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of complications following the posterior and lateral surgical approaches to total hip arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015; 97(1): 11-16. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184904008.

- Post Z D, Orozco F, Diaz-Ledezma C, Hozack W J, Ong A. Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014; 22(9): 595-603. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-09-595.

- Flevas D A, Tsantes A G, Mavrogenis A F. Direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty revisited. JBJS Rev 2020; 8(4): e0144. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00144.

- Van Dooren B, Peters R M, van Steenbergen L N, Post R A J, Ettema H B, Bolder S B T, et al. No clinically relevant difference in patient-reported outcomes between the direct superior approach and the posterolateral or anterior approach for primary total hip arthroplasty: analysis of 37,976 primary hip arthroplasties in the Dutch Arthroplasty Registry. Acta Orthop 2023; 94: 543-9. doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.23729.

- Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Pour A E, Hozack W J. Prospective randomized study of two surgical approaches for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(5): 671-9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.002.

- Ilchmann T, Gersbach S, Zwicky L, Clauss M. Standard transgluteal versus minimal invasive anterior approach in hip arthroplasty: a prospective, consecutive cohort study. Orthop Rev 2013; 5(4): e31. doi: 10.4081/or.2013.e31.

- Gjertsen J-E, Kristensen T B. Annual Report. Norwegian Hip Fractures Register; 2023. Bergen: Health Bergen HF.

- Che Y J, Qian Z, Chen Q, Chang R, Xie X, Hao Y F. Effects of rehabilitation therapy based on exercise prescription on motor function and complications after hip fracture surgery in elderly patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023; 24(1): 817. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06806-y.

- Hoseth J M, Husby O S, Lian Ø B, Myklebust T, Aae T F. Less inflammatory response in the direct anterior than in the direct lateral approach in patients with femoral neck fractures receiving a total hip arthroplasty: exploratory results from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop 2024; 95: 440-5. doi: 10.2340/17453674.2024.41242.

- Kristensen M T, Henriksen S, Stie S B, Bandholm T. Relative and absolute intertester reliability of the timed up and go test to quantify functional mobility in patients with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59(3): 565-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03293.x.

- Gautschi O P, Stienen M N, Corniola M V, Joswig H, Schaller K, Hildebrandt G, et al. Assessment of the minimum clinically important difference in the Timed Up and Go test after surgery for lumbar degenerative disc disease. Neurosurgery 2017; 80(3): 380-5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001320.

- Robinson P G, MacDonald D J, Macpherson G J, Patton J T, Clement N D. Changes and thresholds in the Forgotten Joint Score after total hip arthroplasty: minimal clinically important difference, minimal important and detectable changes, and patient-acceptable symptom state. Bone Joint J 2021; 103-b(12): 1759-65. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B12.BJJ-2021-0384.R1.

- Beard D J, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray D W, Carr A J, et al. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68(1): 73-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.009.

- Technoloy. CRUatNUoSa 2019. Available from: https://www.klinforsk.no/info/WebCRF

- Nairn L, Gyemi L, Gouveia K, Ekhtiari S, Khanna V. The learning curve for the direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Int Orthop 2021; 45(8): 1971-82. doi: 10.1007/s00264-021-04986-7.

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39(2): 142-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x.

- Rix A, Lawrence D, Raper E, Calthorpe S, Holland A E, Kimmel L A. Measurement of mobility and physical function in patients hospitalized with hip fracture: a systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. Phys Ther 2022; 103(1). doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzac142.

- Kristensen M T. Factors influencing performances and indicating risk of falls using the true Timed Up and Go test time of patients with hip fracture upon acute hospital discharge. Physiother Res Int 2020; 25(3): e1841. doi: 10.1002/pri.1841.

- Singh V, Bieganowski T, Huang S, Karia R, Davidovitch R I, Schwarzkopf R. The Forgotten Joint Score patient-acceptable symptom state following primary total hip arthroplasty. Bone Jt Open 2022; 3(4): 307-13. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.34.BJO-2022-0010.R1.

- Freigang V, Weber J, Mueller K, Pfeifer C, Worlicek M, Alt V, et al. Evaluation of joint awareness after acetabular fracture: validation of the Forgotten Joint Score according to the COSMIN checklist protocol. World J Orthop 2021; 12(2): 69-81. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i2.69.

- Anakwe R E, Middleton S D, Jenkins P J, Butler A P, Aitken S A, Keating J F, et al. Total hip replacement in patients with hip fracture: a matched cohort study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73(3): 738-42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182569ee4

- Beckmann M, Bruun-Olsen V, Pripp A H, Bergland A, Smith T, Heiberg K E. Recovery and prediction of physical function 1 year following hip fracture. Physiother Res Int 2022; 27(3): e1947. doi: 10.1002/pri.1947.

- Parsons N, Griffin X L, Achten J, Costa M L. Outcome assessment after hip fracture: is EQ-5D the answer? Bone Joint Res 2014; 3(3): 69-75. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.33.2000250.

- Longo U G, De Salvatore S, Piergentili I, Indiveri A, Di Naro C, Santamaria G, et al. Total hip arthroplasty: minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state for the Forgotten Joint Score 12. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(5). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052267.

- Ugland T O, Haugeberg G, Svenningsen S, Ugland S H, Berg Ø H, Pripp A H, et al. High risk of positive Trendelenburg test after using the direct lateral approach to the hip compared with the anterolateral approach: a single-centre, randomized trial in patients with femoral neck fracture. Bone Joint J 2019; 101-b(7): 793-9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B7.BJJ-2019-0035.R1.

- Saxer F, Studer P, Jakob M, Suhm N, Rosenthal R, Dell-Kuster S, et al. Minimally invasive anterior muscle-sparing versus a transgluteal approach for hemiarthroplasty in femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomised controlled trial including 190 elderly patients. BMC Geriatr 2018; 18(1): 222. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0898-9.

- Innocenti M, Cozzi Lepri A, Civinini A, Mondanelli N, Matassi F, Stimolo D, et al. Functional outcomes of anterior-based muscle sparing approach compared to direct lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty following acute femoral neck fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2023; 14: 21514593231170844. doi: 10.1177/21514593231170844.

- Bűcs G, Dandé Á, Patczai B, Sebestyén A, Almási R, Nöt L G, et al. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures with minimally invasive anterior approach in elderly. Injury 2021; 52(Suppl 1): S37-s43. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.02.053.

- Langlois J, Delambre J, Klouche S, Faivre B, Hardy P. Direct anterior Hueter approach is a safe and effective approach to perform a bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture: outcome in 82 patients. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(3): 358-62. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.1002987.

- Svenoy S, Westberg M, Figved W, Valland H, Brun O C, Wangen H, et al. Posterior versus lateral approach for hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: early complications in a prospective cohort of 583 patients. Injury 2017; 48(7): 1565-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.03.024.

- Skoldenberg O, Ekman A, Salemyr M, Boden H. Reduced dislocation rate after hip arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures when changing from posterolateral to anterolateral approach. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(5): 583-7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.519170.