Risk factors for revision surgery due to dislocation within 1 year after 111,711 primary total hip arthroplasties from 2005 to 2019: a study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register

Peder S THOEN 1–3, Stein Håkon Låstad LYGRE 4,5, Lars NORDSLETTEN 1,3, Ove FURNES 4,6, Hein STIGUM 7, Geir HALLAN 4,6,8, and Stephan M RÖHRL 1

1 Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo; 2 Department of Surgery, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg; 3 Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo; 4 Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen; 5 Department of Occupational Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen; 6 Department of Clinical Medicine (K1), University of Bergen, Bergen; 7 Department of Community Medicine and Global Health (Department of Health and Society), University of Oslo; 8 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Coastal Hospital at Hagevik, Norway

Background and purpose — Dislocation of a hip prosthesis is the 3rd most frequent cause (after loosening and infection) for hip revision in Norway. Recently there has been a shift in surgical practice including preferred head size, surgical approach, articulation, and fixation. We explored factors associated with the risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year and analyzed the impact of changes in surgical practice.

Patients and methods — 111,711 cases of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register were included (2005–2019) after primary THA with either 28 mm, 32 mm, or 36 mm femoral heads, or dual-mobility articulations. A flexible parametric survival model was used to calculate hazard ratios for risk factors. Kaplan–Meier survival rates were calculated.

Results — There was an increased risk of revision due to dislocation with 28 mm femoral heads (HR 2.6, 95% CI 2.0–3.3) compared with 32 mm heads. Furthermore, there was a reduced risk of cemented fixation (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.8) and reverse hybrid (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.8) compared with uncemented. Also, both anterolateral (HR 0.5, CI 0.4–0.7) and lateral (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.7) approaches were associated with a reduced risk compared with the posterior approach. The time-period 2010–2014 had the lowest risk of revision due to dislocation. The trend during the study period was towards using larger head sizes, a posterior approach, and uncemented fixation for primary THA.

Interpretation — Patients with 28 mm head size, a posterior approach, or uncemented fixation had an increased risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA. The shift from lateral to posterior approach and more uncemented fixation was a plausible explanation for the increased risk of revision due to dislocation observed in the most recent time-period. The increased risk of revision due to dislocation was not fully compensated for by increasing femoral head size from 28 to 32 mm.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2022; 93: 593–601. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2022.3474.

Copyright: © 2022 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Submitted: 2021-12-05. Accepted: 2022-06-11. Published: 2022-06-24.

Correspondence: peder.svenkerud.thoen@siv.no

PST is the first author with a main role in study planning, analysing/interpretating data, and writing the manuscript. SHLL is the second author and has conducted statistical analysis and presented data by producing figures and tables. HS has been important in planning statistical analysis and evaluating statistical methodology. OF, GH, LN, and SMR have contributed significantly towards study planning, finalizing protocol, data analysis/interpretation, and writing the final manuscript. All authors have contributed to study planning and finalizing the manuscript.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), including statisticians, secretaries, and IT analysts for entering and preparing data for analysis. They would also like to thank all Norwegian orthopedic surgeons for meticulously reporting THAs to NAR. Lastly, they wish to show appreciation towards all patients who have consented and thereby contributed to this register study.

Acta thanks Lars Lykke Hermansen and Ola Rolfson for help with peer review of this study.

The incidence of dislocation after primary THA ranges from 1.7% to 3.5% (1,2). Approximately 50% of patients who sustain 1 or more dislocations after primary THA end up with revision surgery (3). In 2019, 20% of all revisions in Norway were due to dislocation, according to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) (4). Factors associated with dislocation include patient (age/sex/comorbidities), surgical technique (component positioning/approach) and choice of prosthesis design (head size/dual-mobility/articulation/fixation) (5-9).

During the past 2 decades, arthroplasty surgeons in Norway have changed surgical practice. Uncemented fixation has increased, 32 mm femoral heads are now the standard choice, and both dual-mobility articulations and the use of highly cross-linked polyethylene liners were implemented during the mid-2000s, whereas hip resurfacing was abandoned. The posterior approach is now the most common choice and surpassed the lateral approach in 2015, while the direct anterior (Smith–Petersen) and anterolateral (Watson–Jones) approaches are used in about 20% of patients (4). Currently, we are not aware of the effect of the above-mentioned changes on the revision rates for dislocation.

This study reports factors associated with the risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA. A secondary aim was to report the impact of changes in surgical technique and prosthesis fixation on the risk of revision due to dislocation in 3 time-periods.

Patients and methods

Study population

This is a register-study based on the prospectively collected data from NAR, which is a national population-based register. NAR records THAs in Norway (population 5.2 million) and permits surveillance of contemporary implants and surgical techniques (10). The NAR completeness of reporting range for the years 2008–2018 was 96.7–97.5% for primary THA and 88.3–93.1% for revision surgery when compared with the compulsory Norwegian Patient Registry, and this has remained unchanged since the 1990s (4,11).

We included THAs performed from January 1, 2005 until December 31, 2019 and followed these for 1 year after index surgery. Inclusion criteria were primary THAs with either 28 mm, 32 mm or 36 mm femoral heads, or dual-mobility articulation performed within the inclusion period (2005–2019). Patients operated on with a hip resurfacing prosthesis (metal-on-metal, MoM) or big head MoM (> 36 mm) stemmed prosthesis were excluded. Patients with 22 mm heads were excluded as this head size is no longer relevant in primary THA (not including those in combination with dual-mobility articulation), and 40 mm heads (n = 31) were excluded due to small sample size. 111,711 THAs were included in the study. Each THA was treated as an independent observation, regardless of whether it originated from the same patient (i.e., bilateral THA).

Variables and outcomes

The endpoint in the analyses was revision surgery due to dislocation. Only THAs that underwent revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA surgery were included. Revision surgery due to dislocation superseded any other causes of revision if multiple reasons were registered. The patients were censored if they had revision due to other reasons, were dead, or emigrated. Risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year ensured equal follow-up time for all THAs performed within the inclusion period, and a large proportion of revisions due to dislocation occur in the first year (12).

Statistics

We used STATA SE Version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS Version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analyses. The inclusion period of 15 years was divided into 3 time-periods (2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019) to detect differences over time. The following factors were evaluated for a possible impact on the risk of being revised due to dislocation: head size, duration of surgery, prior operations, time-period of operation, ASA classification, age, surgical approach, diagnosis, fixation, and sex. We opted for using a flexible parametric survival model for the analysis (13). Under standard conditions these models estimate the same as Cox models. However, the flexible models handle deviations for proportional hazards in an easier way and with more opportunities for predictions. We calculated hazard ratios (HR) to evaluate risks for revision due to dislocation for each factor. Reference groups for the HR calculation were based on the group with the highest frequency, most common current practice in Norway, or most recent time-period for all categories (4). In the flexible parametric survival model, time-to-failure event (revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA) was recorded. The proportional hazard assumption was evaluated for all factors both graphically and with numerical p-value to assess differences in hazard ratio during the entire 1-year follow-up period (Supplementary data).

We calculated cumulative survival rates with revision due to dislocation within 1 year using Kaplan–Meier analysis. We also explored cumulative survival using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis stratified by approach for each of the 3 time-periods and separately for the entire inclusion period.

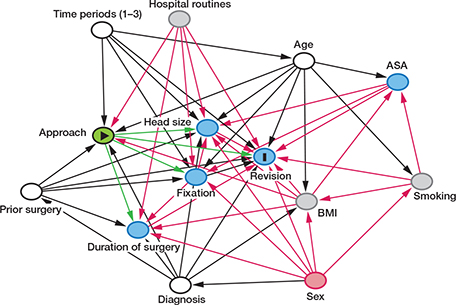

To better identify variables to adjust for in the flexible parametric survival model we developed a directed acyclic graph (DAG). The HR for each exposure was adjusted according to this model. Using the program DAGitty (www.dagitty.net) we determined which factors to adjust for given each specific exposure. The causal inferences and how they influenced each other were represented in a DAG. For each measured factor we created a separate DAG. The DAG (Figure 1) showing which factors were adjusted for in the flexible parametric survival model given each specific exposure are listed at the bottom of Table 2..

Figure 1. Directed acyclic graph (DAG) showing approach as exposure (E, yellow) and revision due to dislocation as outcome (O, dark blue). Other associated factors are listed with arrows depicting causality towards E and O. Smoking, hospital routines, and BMI are listed as unobserved factors (grey). Age, diagnosis, prior operations, and time periods are confounding factors (white) and should be adjusted for. Sex is an ancestor of E and O (red) and should not be adjusted for (sex does not influence the exposure directly). Head size, fixation, duration of surgery, and ASA are mediators (blue) and should not be adjusted for since this potentially could introduce bias. For each measured factor we created a separate DAG similar to the one depicted for approach (above) in order to determine which factors to adjust for in flexible parametric survival model.

The study is reported in accordance with the RECORD guidelines.

Ethics and potential conflicts of interest

Registration of data in NAR and the present register study is based on informed consent from patients and according to the Norwegian Data Protection Regulations (reference number 03/00058-20/CGN) and EU regulations. There is no conflict of interest declared.

Results

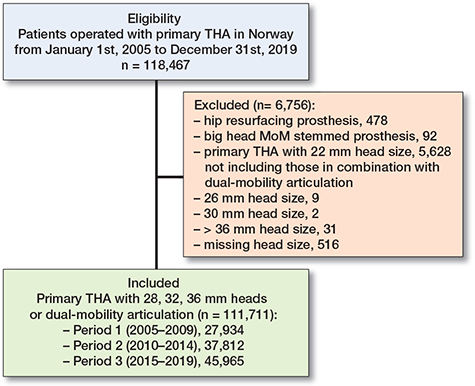

Between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2019, there were 118,467 primary THAs recorded in NAR. 111,711 (94%) of these THAs were included in this study according to the inclusion criteria (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Flowchart showing distribution of eligible and included patients from January 1, 2005 until December 31, 2019. Included patients were divided into 3 time-periods based on time of operation to evaluate differences over time. MoM = metal-on-metal

| Factor | Period 1 2005–2009 n = 27,934 | Period 2 2010–2014 n = 37,812 | Period 3 2015–2019 n = 45,965 | Total n = 111,711 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 68.7 (11.5) | 68.3 (11.3) | 68.3 (11.3) | 68.4 (11.3) |

| Females | 18,776 (67) | 24,591 (65) | 29,440 (64) | 72,807 (65) |

| Males | 9,158 (33) | 13,221 (35) | 16,525 (36) | 38,904 (35) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 21,635 (78) | 29,868 (79) | 36,632 (80) | 88,135 (79) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 560 (2.0) | 624 (1.7) | 539 (1.2) | 1,723 (1.5) |

| Sequelae after | ||||

| femoral neck fracture | 1,978 (7.1) | 1,746 (4.6) | 1,567 (3.4) | 5,291 (4.7) |

| dysplasia | 2,080 (7.4) | 2,972 (7.9) | 3,249 (7.1) | 8,301 (7.4) |

| with high dislocation | 98 (0.4) | 93 (0.2) | 77 (0.2) | 268 (0.2) |

| Perthes disease | 38 (0.1) | 260 (0.7) | 393 (0.9) | 691 (0.6) |

| epiphysiolysis | 0 (0.0) | 78 (0.2) | 131 (0.3) | 209 (0.2) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 95 (0.3) | 145 (0.4) | 107 (0.2) | 347 (0.3) |

| Femoral neck fracture | 510 (1.8) | 1,088 (2.9) | 2,226 (4.8) | 3,824 (3.4) |

| Other | 1,690 (6.0) | 2,069 (5.5) | 2,668 (5.8) | 6,427 (5.8) |

| Missing | 65 (0.2) | 138 (0.4) | 72 (0.2) | 275 (0.2) |

| Head size | ||||

| 28 mm | 23,913 (86) | 17,987 (48) | 3792 (8.2) | 45,692 (41) |

| 32 mm | 3,019 (11) | 16,700 (44) | 36,351 (79) | 56,070 (50) |

| 36 mm | 684 (2.4) | 2,314 (6.1) | 4,466 (9.7) | 7,464 (6.7) |

| Dual-mobility | 318 (1.1) | 811 (2.1) | 1,356 (3.0) | 2,485 (2.2) |

| Fixation | ||||

| Cemented | 16,767 (60) | 11,929 (32) | 12,444 (27) | 41,140 (37) |

| Hybrid | 467 (1.7) | 693 (1.8) | 3,876 (8.4) | 5,036 (4.5) |

| Reverse hybrid | 5,255 (19) | 14,551 (39) | 11,942 (26) | 31,748 (28) |

| Uncemented | 5,207 (19) | 10,058 (27) | 17,451 (38) | 32,716 (29) |

| Missing | 238 (0.9) | 581 (1.5) | 252 (0.5) | 1,071 (1.0) |

| Approach | ||||

| Direct anterior (S–P) a | 412 (1.5) | 2,165 (5.7) | 3,461 (7.5) | 6,038 (5.4) |

| Anterolateral (W–J) a | 1,523 (5.5) | 4,282 (11) | 6,139 (13) | 11,944 (11) |

| Direct lateral | 17,395 (62) | 17,908 (47) | 5,250 (11) | 40,553 (36) |

| Posterior | 8,114 (29) | 11,729 (31) | 29,210 (64) | 49,053 (44) |

| Other | 30 (0.1) | 130 (0.3) | 77 (0.2) | 237 (0.2) |

| Missing | 459 (1.6) | 1,598 (4.2) | 1,824 (4.0) | 3,881 (3.5) |

| Duration of surgery | ||||

| 0–60 minutes | 1,867 (6.7) | 4,932 (13.0) | 7,842 (17) | 14,641 (13) |

| 60–90 minutes | 11,695 (42) | 15,704 (42) | 20,413 (44) | 47,812 (43) |

| 90–120 minutes | 9,059 (32) | 10,756 (28) | 11,577 (25) | 31,392 (28) |

| > 120 minutes b | 4,903 (18) | 5,557 (15) | 5,352 (12) | 15,812 (14) |

| Missing | 410 (1.5) | 863 (2.3) | 781 (1.7) | 2,054 (1.8) |

| ASA classification: | ||||

| 1–2 | 21,868 (78) | 30,031 (79) | 36,003 (78) | 87,902 (79) |

| ≥ 3 | 5,092 (18) | 7,390 (20) | 9,601 (21) | 22,083 (20) |

| Missing | 974 (3.5) | 391 (1.0) | 361 (0.8) | 1,726 (1.5) |

| Prior operations | ||||

| Yes | 2,755 (9.9) | 2,790 (7.4) | 2,991 (6.5) | 8,536 (7.6) |

| No | 25,161 (90) | 35,012 (93) | 42,962 (94) | 103,135 (92) |

| Missing | 18 (0.1) | 10 (0.0) | 12 (0.0) | 40 (0.0) |

| Revisions due to dislocation | ||||

| within 1 year | 170 (0.6) | 157(0.4) | 300 (0.7) | 627 (0.5) |

| a S–P = Smith-Petersen; W–J =Watson-Jones. b Reported values > 600 minutes for the duration of surgery category are set as “missing.” |

||||

Risk factors for revision due to dislocation

There was an increased risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA with 28 mm femoral heads (HR 2.6, 95% CI 2.0–3.3) compared with 32 mm heads. The risk of revision due to dislocation was reduced for cemented (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.8) and reverse hybrid (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.8) fixations compared with uncemented. Both anterolateral (HR 0.5, CI 0.4–0.7) and lateral (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.7) approaches were associated with a reduced risk compared with the posterior approach. However, the direct anterior approach (HR 0.8, CI 0.6–1.2) was not associated with a reduced risk compared with the posterior approach.

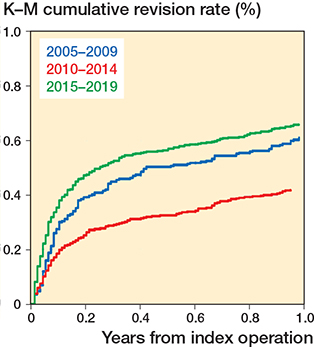

Cumulative survival rates

Kaplan–Meier curves stratified for time-period showed the highest cumulative survival rate for Time-period 2 (2010–2014), and similar rates for Time-period 1 (2005–2009) and Time-period 3 (2015–2019) (Figure 3 and Table 2). Adjusting for head size removed the difference between Time-periods 1 and 2 (not shown). When the Kaplan–Meier curves were stratified by approach for the 3 time-periods, the direct anterior and anterolateral approaches had the lowest cumulative survival rates (free of revision for dislocation) in Time-period 1, and anterolateral the highest survival rate in Time-period 3 (not shown). There was no apparent difference between the lateral and posterior approach in Time-period 1, but a difference was observed in Time-period 3 (posterior approach had lowest survival). In Time-period 3 the posterior approach had a lower cumulative survival rate than in Time-period 1.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the 3 time-periods, 1–3 (2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019) showing cumulative revision for dislocation within 1 year from primary THA.

| Number of primary THAs | Revisions due to dislocation ≤ 1 year, n (%) | 1–year survival (CI) | Flexible parametric survival model | ||||

| Unadjusted HR (CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (CI) | p-value | ||||

| Age a | |||||||

| < 60 | 22,946 | 113 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.4–99.6) | 0.81 (0.65–1.02) | 0.07 | 0.81 (0.65–1.02) | 0.09 |

| 60–70 | 35,222 | 165 (0.5) | 99.6 (99.5–99.6) | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) | 0.01 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 0.03 |

| 70–80 | 37,371 | 226 (0.6) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| > 80 | 16,172 | 123 (0.8) | 99.3 (99.1–99.4) | 1.27 (1.02–1.59) | 0.03 | 1.29 (1.03–1.60) | 0.04 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 38,904 | 276 (0.7) | 99.3 (99.2–99.4) | 1.48 (1.27–1.73) | < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 72,807 | 351 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.5–99.6) | 1 (reference) | |||

| Diagnosis c | |||||||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 88,135 | 414 (0.5) | 99.6 (99.5–99.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Other | 23,576 | 213 (0.9) | 99.1 (99.0–99.2) | 1.94 (1.65–2.29) | < 0.001 | 1.93 (1.63–2.27) | < 0.001 |

| Head size d | |||||||

| 28 mm | 45,692 | 284 (0.6) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 1.25 (1.06–1.47) | 0.009 | 2.59 (2.03–3.31) | < 0.001 |

| 32 mm | 56,070 | 279 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.5–99.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| 36 mm | 7,464 | 44 (0.6) | 99.4 (99.2–99.6) | 1.19 (0.86–1.63) | 0.3 | 0.74 (0.53–1.05) | 0.09 |

| Dual-mobility | 2,485 | 20 (0.8) | 99.2 (98.8–99.5) | 1.68 (1.07–2.64) | 0.03 | 0.70 (0.40–1.25) | 0.2 |

| Fixation e | |||||||

| Cemented | 41,140 | 224 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.4–99.5) | 0.75 (0.63–0.91) | 0.002 | 0.61 (0.49–0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Hybrid | 5,036 | 37 (0.7) | 99.3 (99.0–99.5) | 1.02 (0.72–1.45) | 0.9 | 0.77 (0.54–1.10) | 0.1 |

| Reverse hybrid | 31,748 | 116 (0.4) | 99.7 (99.6–99.7) | 0.51 (0.40–0.63) | < 0.001 | 0.62 (0.49–0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Uncemented | 32,716 | 236 (0.7) | 99.3 (99.2–99.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Approach f | |||||||

| Direct anterior (S–P) | 6,038 | 30 (0.5) | 99.6 (99.3–99.7) | 0.68 (0.47–0.99) | 0.046 | 0.80 (0.55–1.16) | 0.2 |

| Anterolateral (W–J) | 11,944 | 38 (0.4) | 99.7 (99.6–99.8) | 0.44 (0.31–0.61) | < 0.001 | 0.49 (0.35–0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Direct lateral | 40,553 | 182 (0.5) | 99.6 (99.5–99.6) | 0.62 (0.52–0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.48–0.72) | < 0.001 |

| Posterior | 49,053 | 356 (0.7) | 99.3 (99.2–99.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 | ||

| Duration of surgery g | |||||||

| 0–60 minutes | 14,641 | 70 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.4–99.6) | 1.04 (0.80–1.36) | 0.8 | 0.85 (0.64–1.12) | 0.2 |

| 60–90 minutes | 47,812 | 219 (0.5) | 99.6 (99.5–99.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| 90–120 minutes | 31,392 | 189 (0.6) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 1.32 (1.09–1.60) | 0.005 | 1.37 (1.12–1.68) | 0.002 |

| > 120 minutes | 15,812 | 131 (0.8) | 99.2 (99.1–99.3) | 1.82 (1.47–2.26) | < 0.001 | 1.79 (1.42–2.26) | < 0.001 |

| ASA classification h | |||||||

| 1–2 | 87,902 | 423 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.5–99.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 22,083 | 193 (0.9) | 99.1 (99.0–99.3) | 1.85 (1.56–2.20) | < 0.001 | 1.74 (1.46–2.08) | < 0.001 |

| Prior operations i | |||||||

| Yes | 8,536 | 97 (1.1) | 98.9 (98.6–99.1) | 2.25 (1.81–2.79) | < 0.001 | 1.57 (1.22–2.02) | 0.001 |

| No | 103,135 | 530 (0.5) | 99.5 (99.5–99.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Time periods (1–3) j | |||||||

| 2005–2009 | 27,934 | 170 (0.6) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) | 0.4 | ||

| 2010–2014 | 37,812 | 157 (0.4) | 99.6 (99.5–99.7) | 0.64 (0.52–0.77) | < 0.001 | ||

| 2015–2019 | 45,965 | 300 (0.7) | 99.4 (99.3–99.4) | 1 (reference) | |||

| a Adjustments for Time periods. b No adjustment. c Adjustments for Sex. d Adjustment for ASA, Age, Approach, Diagnosis, Fixation, Prior operations, Sex, Time periods. e Adjustments for Age, Approach, Diagnosis, Prior operations, Sex, Time periods. f Adjustments for Age, Diagnosis, Prior operations, Time periods. g Adjustments for Approach, Diagnosis, Fixation, Prior operations, Sex. h Adjustments for Age. i Adjustments for Diagnosis. j No adjustment. |

|||||||

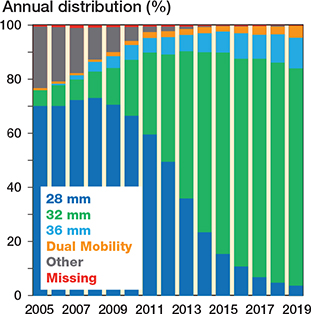

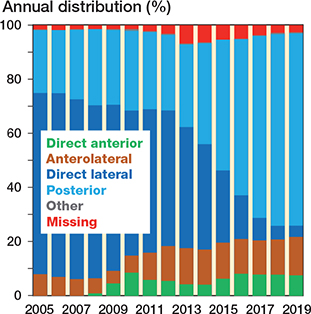

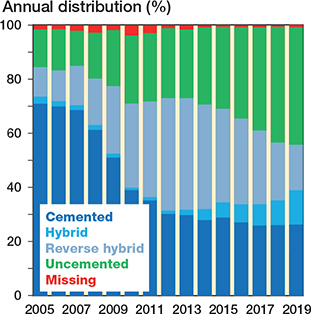

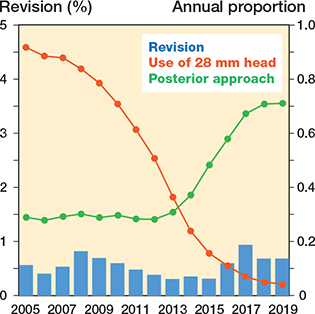

Trends

The trends over time regarding femoral head size, surgical approach, and fixation are represented in bar charts (Figures 4–7). The trend during the study period was towards using larger head sizes, a posterior approach, and uncemented fixation. The relationships between annual early revision rate (%) due to dislocation (within 1 year) and both posterior approach and head size are illustrated in Figure 7. Generally, annual revision rate due to dislocation was low (< 1%); however, there was a trend towards an increasing revision risk in the most recent time-period (2015–2019), when most of the THAs were performed using larger head sizes and posterior approach (HR 0.6, CI 0.5–0.8, for 2010–2014 compared with 2015–2019). There was no difference between the 1st and last time-period (Table 2).

Figure 4. Bar chart showing different femoral head sizes and dual-mobility articulations for all primary THAs performed in Norway from January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2019 (based on eligible patients, n = 118,467). “Other” category contains hip resurfacing prosthesis, big head metal-on-metal stemmed prosthesis, 26 mm, 30 mm, and > 36 mm head sizes.

Figure 5. Bar chart showing surgical approach for all primary THAs performed in Norway from January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2019 (based on eligible patients, n = 118,467). “Other” category contains trochanteric osteotomy.

Figure 6. Bar chart showing different fixation combinations for all primary THAs performed in Norway from January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2019 (based on eligible patients, n = 118,467).

Figure 7. Relationship between annual rate (%) of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA (blue bars) and use of 28 mm heads and posterior approach depicted in the graph as their annual proportion.

Discussion

The main factors associated with an increased risk of revision due to dislocation were 28 mm head size, posterior approach, and uncemented fixation.

The risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after THA was lower in the 2nd time-period compared with the 1st time-period and were at a level in the last time-period similar to that of the 1st time-period.

The shift from lateral to posterior approach and more uncemented fixation was a plausible explanation for the slightly increased risk of revision due to dislocation observed in the most recent time-period.

Head size

28 mm femoral heads were associated with an increased risk of due to dislocation compared with 32 mm and 36 mm heads, and dual-mobility articulations. Interestingly, for this analysis the unadjusted model showed a different trend. Dual-mobility articulations appeared to have an increased risk, but when adjusting (ASA class, age, approach, diagnosis, fixation, prior operations, sex, and time-period) there was a trend towards a reduced risk (similar finding with 36 mm head sizes). An explanation for this discrepancy is likely selection bias. Patients at high risk of dislocation most likely have been selected for dual-mobility articulations or 36 mm head sizes. Another important detail is that the HR for 28 mm head size was 1.3 in the unadjusted model and 2.6 in the adjusted model. Not adjusting for approach resulted in a lower risk because the majority of the 28 mm femoral heads were used with a lateral approach, which had a reduced risk of dislocation compared with a posterior approach. This has also been found by others (5). A study from 2018 found a reduced risk of revision for 32 mm compared with 28 mm heads, but there was no added benefit in going from 32 mm to 36 mm heads (14).

Currently, the use of 36 mm heads (n = 4,466, 2015–2019) and dual-mobility articulations (n = 1,356, 2015–2019) is quite limited in primary cases in Norway. Commonly, orthopedic surgeons in Norway reserve 36 mm head sizes and dual-mobility articulations for patients thought to be at increased risk of dislocation. We found that the dislocation risk with 36 mm heads and DM articulations was similar to that of 32 mm heads (n = 36,351, 2015–2019), and this finding indicates that the revision risk for patients at high risk of dislocation is successfully reduced with these measures. Using dual-mobility articulations in THA following hip fracture has shown lower risk of revision compared with conventional THA in a combined Nordic register study (15). In a recent Danish register study by Hermansen et al., 32 mm heads had a higher risk of dislocation compared with 36 mm heads, and dual-mobility articulations a lower risk than 36 mm heads (2). Interestingly, our risk estimates showed a similar, but not statistically significant trend. This difference may be related to patient selection and/or power as the relative number of patients receiving 36 mm heads is substantially higher in Denmark, and 36 mm heads are used in a more unselected group of patients (2).

Approach

The posterior approach was associated with an increased risk of revision due to dislocation compared with the lateral and anterolateral approaches. This has also been documented in other studies (2,5,8,16,17). However, this in isolation does not justify abandoning this approach due to considerations such as lower overall complication rate (18), and infrequently occurring complications such as Trendelenburg gait, which is more common with a lateral approach (19). One reason we did not find a difference in risk of revision due to dislocation between the direct anterior and the posterior approach may have been a learning curve effect (Figure 5). To the contrary, the learning curve effect for the anterolateral approach was likely not present in our study because this approach was introduced prior to our inclusion period (2005–2019). In the NAR article by Mjaaland et al. from 2017 (17), the 2 anterior approaches (anterolateral, direct anterior) were combined and compared with the lateral approach (inclusion period 2008–2013). They found no difference in risk of revision due to dislocation between the anterior approaches as a combined group compared with the lateral approach. The learning curve effect for the direct anterior approach may have been masked as a result of combining the two anterior approaches.

Fixation

There was an increased risk of revision due to dislocation for uncemented THA, which is consistent with the literature (20). Some claim that precise positioning of uncemented components is more challenging than cemented components, and that this increases the risk of dislocation (20).

Age, sex, diagnosis, ASA class, and duration of surgery

The factors high age, male sex, diagnosis other than OA, ASA classification ≥ 3, and long operation time were associated with an increased risk of revision due to dislocation, and this has also been shown by other authors (2,7–9,16,21,22).

Prior operations

A prior operation on the hip implicated a higher revision risk due to dislocation. However, this patient group with a prior operation is heterogeneous and estimates may be uncertain.

Time-periods

THAs performed in Time-period 1 (2005–2009) and Time-period 3 (2015–2019) had an increased risk of revision due to dislocation compared with THAs in Time-period 2 (2010–2014). There was no difference between Time-period 1 and Time-period 3 (Table 2). We did no adjustments for time-period as an exposure in the flexible parametric survival model (Table 2) because there were no observed factors that exerted an influence on this exposure. The higher risk of revision due to dislocation in Time-period 3 coincides with an increased use of the posterior approach and more use of uncemented implants in recent years. A Swedish register study including 156,979 THAs from 1999 to 2014 found that in the earliest time-period (1999–2006) there was an increased risk of revision due to dislocation for the posterior approach compared with the lateral approach. However, no difference was found in the latest time-period (2007–2014) (23).

Adjusting for head size in the flexible parametric model removed the difference observed between Time-periods 1 and 2. This has a logical connotation since there were substantially more 28 mm head sizes used in Time-period 1 compared with the other two time-periods (Figures 4 and 7). Adjusting for approach in the 3 time-periods did not fully compensate for the differences due to different effects of approach in the 3 time-periods.

The direct anterior and anterolateral approaches had the lowest survival rates in Time-period 1. On the other hand, the anterolateral approach had the highest survival rate in Time-period 3 (direct anterior approach 3rd highest). This discrepancy between time-periods is likely due to a learning curve effect (24). In a NAR study from 2017, comparing approaches and implant survival, the direct anterior and anterolateral approaches were not included prior to 2008 due to a proposed initial learning curve effect and few patients. Also, there were no differences in survival between these 2 anterior approaches and the lateral or posterior approaches (17). In our study, there was no observed difference between the lateral and posterior approaches in Time-period 1, but there was a difference in Time-period 3 when the posterior approach had a lower survival rate than the lateral. In addition, the posterior approach had a lower survival rate in Time-period 3 than in Time-period 1. This can be explained by a learning curve effect as many surgeons have swapped from lateral to posterior approach in recent times. The hospitals in Norway using the posterior approach during Time-period 1 were high-volume centers that had been using the posterior approach for a long time. Currently, the posterior approach is the most commonly used approach in Norway (Figures 5 and 7).

Strengths and limitations

The study setting (NAR) and trends reflect clinical practice in Norway and this leads to a high external validity for THA practice in Norway, and presumably internationally. The following aspects add to the external validity of the study: high number of included patients, high completeness of reporting in NAR (few eligible patients are missed), multicenter enrolment, and multiple surgeons involved. Data reported to NAR has been validated and found valid and reliable (25). Completeness of data is poorer for revision surgery (1.2% missing) compared with primary operations (0.2% missing). However, specific causes for revision surgery (including revision due to dislocation) have currently not been validated (25). While there is a theoretical dependency between THAs in the same patient in arthroplasty register studies (i.e., bilateral THAs), no impact has been shown on the analysis and ignoring this possible dependency does not necessarily have an impact on the results (26,27).

Another strength of this study was creating a directed acyclic graph (DAG) prior to data analysis to evaluate which factors to adjust for in the flexible parametric survival model (Figure 1). DAGs are illustrative graphs depicting causal inference pathways and are based on existing literature and clinical experience. It is valuable to complete a thorough a priori evaluation of possible causal pathways in a dataset to determine which factors to adjust for in a model, and thereby limit bias and avoid Table II fallacy—adjusting for all known factors without causal pathway consideration (28).

Possible confounding factors that we were not able to control for were factors such as smoking, BMI, and hospital routines (i.e., patient position routines, surgeon experience). In addition, social factors (i.e., income, social deprivation, and ethnicity) and other comorbidities such as previous spinal surgery (hip–spine syndrome) are not reported in NAR. Register studies may uncover associations between studied variables and revision causes but cannot claim causality (29).

The decision to undergo revision surgery due to dislocation is multi-faceted and based on shared decision-making between the patient and surgeon. There is no absolute consensus among orthopedic surgeons regarding when to advocate revision surgery. Some patients suffer from dislocation; however, they have not been reported in this study because not all undergo surgery. Revision surgery due to dislocation is an indirect measure of hip dislocation, and the actual number of dislocations is likely substantially larger than the number of revisions (30). In NAR, only patients who have undergone revision surgery are registered whereas at present closed reductions of dislocation are not. Thus, our study is not on the risk of dislocation, but on the risk of revision surgery due to dislocation and a subgroup of patients revised due to dislocation within the 1st year after primary THA. In general, the rate of revision due to dislocation is low (< 1%), and the difference between the 3 observed time-periods is small. Also, some patients may have more than one reason for revision.

Conclusions

We found an increased risk of revision due to dislocation within 1 year after primary THA when using 28 mm head size compared with 32 or 36 mm head sizes, or with dual-mobility articulation. Also, there was an increased risk both when using a posterior approach compared with lateral and anterolateral approaches, and when using uncemented fixation compared with cemented and reverse hybrid fixations. The shift from lateral to posterior approach and more use of uncemented THA may be a plausible explanation for the slightly increased risk of revision due to dislocation observed in the most recent time-period on a national level.

- Khatod M, Barber T, Paxton E, Namba R, Fithian D. An analysis of the risk of hip dislocation with a contemporary total joint registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 447: 19-23.

- Hermansen L L, Viberg B, Hansen L, Overgaard S. “True” cumulative incidence of and risk factors for hip dislocation within 2 years after primary total hip arthroplasty due to osteoarthritis: a nationwide population-based study from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021; 103(4): 295-302.

- Hedlundh U, Ahnfelt L, Hybbinette C H, Wallinder L, Weckström J, Fredin H. Dislocations and the femoral head size in primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996(333): 226-33.

- NAR. Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR). Annual Report 2020. Available from: https://helse-bergen.no/nrl.

- Berry D J, von Knoch M, Schleck C D, Harmsen W S. Effect of femoral head diameter and operative approach on risk of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(11): 2456-63.

- Furnes O, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements: a review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987–99. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83(4): 579-86.

- Hailer N P, Weiss R J, Stark A, Kärrholm J. The risk of revision due to dislocation after total hip arthroplasty depends on surgical approach, femoral head size, sex, and primary diagnosis. An analysis of 78,098 operations in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(5): 442-8.

- Zijlstra W P, De Hartog B, Van Steenbergen L N, Scheurs B W, Nelissen R. Effect of femoral head size and surgical approach on risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2017; 88(4): 395-401.

- Kunutsor S K, Barrett M C, Beswick A D, Judge A, Blom A W, Wylde V, et al. Risk factors for dislocation after primary total hip replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 125 studies involving approximately five million hip replacements. Lancet Rheumatol 2019; 1(2): e111-e21.

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(4): 337-53.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(1): 49-56.

- Shen T S, Gu A, Bovonratwet P, Ondeck N T, Sculco P K, Su E P. Etiology and complications of early aseptic revision total hip arthroplasty within 90 days. J Arthroplasty 2021; 36(5): 1734-9.

- Crowther M J, Lambert P C. A general framework for parametric survival analysis. Stat Med 2014; 33(30): 5280-97.

- Tsikandylakis G, Kärrholm J, Hailer N P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä K T, Hallan G, et al. No increase in survival for 36-mm versus 32-mm femoral heads in metal-on-polyethylene THA: a registry study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018; 476(12): 2367-78.

- Jobory A, Kärrholm J, Overgaard S, Becic Pedersen A, Hallan G, Gjertsen J E, et al. reduced revision risk for dual-mobility cup in total hip replacement due to hip fracture: a matched-pair analysis of 9,040 cases from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019; 101(14): 1278-85.

- Panula V J, Ekman E M, Venäläinen M S, Laaksonen I, Klén R, Haapakoski J J, et al. Posterior approach, fracture diagnosis, and American Society of Anesthesiology class III–IV are associated with increased risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of 33,337 operations from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Scand J Surg 2020:1457496920930617.

- Mjaaland K E, Svenningsen S, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Nordsletten L. Implant survival after minimally invasive anterior or anterolateral vs. conventional posterior or direct lateral approach: an analysis of 21,860 total hip arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (2008 to 2013). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; 99(10): 840-7.

- Aggarwal V K, Elbuluk A, Dundon J, Herrero C, Hernandez C, Vigdorchik J M, et al. Surgical approach significantly affects the complication rates associated with total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2019; 101-b(6): 646-51.

- Amlie E, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Baste V, Nordsletten L, Hovik O, et al. Worse patient-reported outcome after lateral approach than after anterior and posterolateral approach in primary hip arthroplasty: a cross-sectional questionnaire study of 1,476 patients 1-3 years after surgery. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(5): 463-9.

- Clement N D, Biant L C, Breusch S J. Total hip arthroplasty: to cement or not to cement the acetabular socket? A critical review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132(3): 411-27.

- Hedlundh U, Ahnfelt L, Hybbinette C H, Weckstrom J, Fredin H. Surgical experience related to dislocations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78(2): 206-9.

- Rowan F E, Benjamin B, Pietrak J R, Haddad F S. Prevention of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018; 33(5): 1316-24.

- Skoogh O, Tsikandylakis G, Mohaddes M, Nemes S, Odin D, Grant P, et al. Contemporary posterior surgical approach in total hip replacement: still more reoperations due to dislocation compared with direct lateral approach? An observational study of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register including 156,979 hips. Acta Orthop 2019; 90(5): 411-16.

- Brun O-CL, Månsson L, Nordsletten L. The direct anterior minimal invasive approach in total hip replacement: a prospective departmental study on the learning curve. Hip Int 2018; 28(2): 156-60.

- Arthursson A J , Furnes O, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Söreide J A. Validation of data in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register and the Norwegian Patient Register: 5,134 primary total hip arthroplasties and revisions operated at a single hospital between 1987 and 2003. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(6): 823-8.

- Lie S A, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Stat Med 2004; 23(20): 3227-40.

- Ranstam J, Kärrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Mäkelä K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, et al. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data, I: Introduction and background. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(3): 253-7.

- Westreich D, Greenland S. The table 2 fallacy: presenting and interpreting confounder and modifier coefficients. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177(4): 292-8.

- Inacio M C, Paxton E W, Dillon M T. Understanding orthopaedic registry studies: a comparison with clinical studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98(1): e3.

- Hermansen L L, Viberg B, Overgaard S. Development of a diagnostic algorithm identifying cases of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty-based on 31,762 patients from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2021; 92(2): 137-42.

Supplementary data

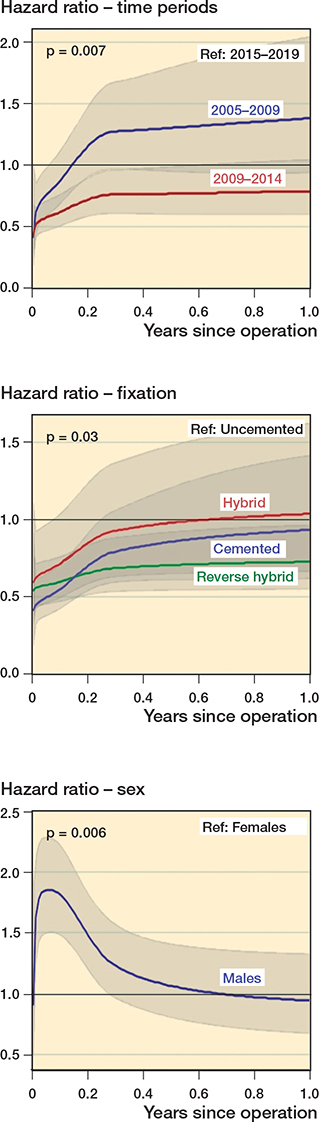

Test of proportional hazard assumption

All 10 factors evaluated were tested regarding the proportional hazard assumption. The 3 factors time-periods, fixation, and sex did not meet the proportional hazard assumption (p-values < 0.05 as given above). Graphic representation of the fluctuation of the hazard ratio for each of the 3 factors during the 1-year follow-up period is shown to the right. As an example, the hazard ratio for males was much higher in reference to females during the beginning (initial 2 months) of the 1-year follow-up period.

Proportional hazard assumption

All factors met the proportional hazard assumption except for time-period (p = 0.007), fixation (p = 0.03), and sex (p = 0.006). During the 1st year after primary THA, the risk for revision due to dislocation for the 1st time-period (2005–2009) compared with the last (2015–2019) was the same (HR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–1.1) (Table 2). However, for the initial 2 months the risk was lower (HR < 1) for the 1st time-period compared with the last. For the cemented, hybrid, and reverse hybrid fixations there was a lower risk of revision in the initial 3 months before leveling out compared with uncemented fixation. Males showed an initial spike in risk of revision due to dislocation during the initial 2 months, and there was a higher risk for males (HR < 1) compared with females in the first 6 months after primary THA. After the first 6 months the risk of revision due to dislocation for males compared with females was similar (HR~1). The time-varying hazard ratios for time-period, fixation, and sex are illustrated to the right.

For the 3 factors that did not meet the proportional hazard assumption (time-period, fixation, sex) the hazard ratios were not constant throughout the entire follow-up period (1 year follow-up). The greatest variation in hazard ratios for these factors was seen in the initial 3 months of follow-up as shown to the right.