A matched comparison of cementless unicompartmental and total knee replacement outcomes based on the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man

Hasan R MOHAMMAD 1,2, Andrew JUDGE 1,2, and David W MURRAY 1

1 Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences University of Oxford, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford; 2 Musculoskeletal Research Unit, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Southmead Hospital, Westbury-on-Trym, UK

Background and purpose — The main treatments for severe medial compartment knee arthritis are unicompartmental (UKR) and total knee replacement (TKR). UKRs have higher revision rates, particularly for aseptic loosening, therefore the cementless version was introduced. We compared the outcomes of matched cementless UKRs and TKRs.

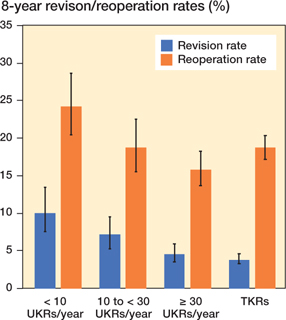

Patients and methods — The National Joint Registry was linked to the English Hospital Episode Statistics and Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) databases. 10,552 cementless UKRs and 10,552 TKRs were propensity matched and regression analysis used to compare revision/reoperation risks. 6-month PROMs were compared. UKR results were stratified by surgeon caseload into low- (< 10 UKRs/year), medium- (10 to < 30 UKRs/year), and high-volume (≥ 30 UKRs/year).

Results — 8-year cementless UKR revision survival for the 3 respective caseloads were 90% (95% CI 87–93), 93% (CI 91–95), and 96% (CI 94–97). 8-year reoperation survivals were 76% (CI 71–80), 81% (CI 78–85), and 84% (CI 82–86) respectively. For TKR the 8-year implant survivals for revision and reoperation were 96% (CI 95–97) and 81% (CI 80–83). The HRs for the 3 caseload groups compared with TKR for revision were 2.0 (CI 1.3–2.9), 2.0 (CI 1.6–2.7), and 1.0 (CI 0.8–1.3) and for reoperation were 1.2 (CI 1.0–1.4), 0.9 (CI 0.8–1.0), and 0.6 (CI 0.5–0.7). 6-month Oxford Knee Score (OKS) (39 vs. 37) and EQ-5D (0.80 vs. 0.77) were higher (p < 0.001) for the cementless UKR.

Interpretation — Cementless UKRs have higher revision and reoperation rates than TKR for low-volume UKR surgeons, similar reoperation but higher revision rates for mid-volume surgeons, and lower reoperation and similar revision rates for high-volume surgeons. Cementless UKR also had better PROMs.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2022; 93: 478–487. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2022.2743.

Copyright: © 2022 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Submitted: 2022-01-30. Accepted: 2022-04-06. Published: 2022-05-24.

Correspondence: hasanmohammad@doctors.org.uk

HRM, AJ, and DWM designed the study. HRM and DWM analyzed the data with statistical support from AJ. HRM, AJ, and DWM helped with data interpretation. HRM wrote the initial manuscript draft which was then revised appropriately by all authors.

The authors would like to thank the patients and staff of all the hospitals in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Isle of Man who have contributed data to the National Joint Registry. They are grateful to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), the NJR Research Sub-committee, and staff at the NJR Centre for facilitating this work. The authors have conformed to the NJR’s standard protocol for data access and publication. The views expressed represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Joint Registry Steering Committee or the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), who do not vouch for how the information is presented.

The main treatment options for severe medial compartment knee arthritis are total (TKR) and unicompartmental (UKR) knee replacements. UKR has advantages over TKR, including reduced mortality and improved functional outcomes (1-3). However, the registries show several times higher revision rates (4-6).

Analyses comparing UKR and TKR using registries generally combine all implants and surgeons, whatever their caseload. This approach is suitable for TKR, given that commonly used TKR implants have similar revision rates and surgeon caseload has little influence (7). However, the situation is different for UKR where the results differ considerably. The commonest number of UKR done per surgeon per year is 1 or 2 and these surgeons have revision rates of about 4% per year (7). In contrast, surgeons with higher caseloads have much lower UKR revision rates. Therefore, to compare UKR with TKR, it may be best to focus on a single well performing UKR and subdivide surgeons according to their UKR caseload. The National Joint Registry (NJR) collects data every time a joint replacement is inserted so a revision is generally considered to occur when a new implant is added. Patients need more information and need to know the rate of all reoperations, including those which do not meet the revision definition. These non-revsion reoperations have a spectrum of severity extending from amputation or internal fixation to arthroscopy or manipulation under anesthetic (8).

The most commonly used UKR is the mobile-bearing Oxford (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA). Given that leading causes for UKR revision include aseptic loosening and pain (9), a cementless version was introduced (10). The results of the cementless Oxford UKR have not been compared with TKR. This study compares clinical outcomes of matched cementless Oxford UKRs and TKRs and subdivides UKR according to surgeon caseload.

Methods

Databases

NJR records were linked to the Hospital Episodes Statistics Admitted Patient Records (HES-APC) and Patient Reported Outcome Measures (HES-PROMs) database. The NJR is the world’s largest arthroplasty register (5). HES-APC is a database of all admission episodes for patients admitted to National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England and contains information including comorbidities, medical complications, and reoperations (11). The HES-PROMs database was created from approximately 2009 onwards. All NHS-funded knee replacements have preoperative and 6-month postoperative PROMs recorded (12). These include the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) (13) and quality of life EuroQol 5 Domain index (EQ-5D) (14). The time intervals used by the program were a compromise between surgery proximity and sufficient follow-up whilst accounting for the postoperative recovery period. Research indicates most improvement in PROMs after joint replacement occurs in the first 6 months, with only minor improvement between 6 months and 1 year (15). Long-term studies of TKR and UKR have shown that PROMs remain relatively constant after this, at least up to the 10-year point (16,17).

Cohorts

An a priori decision was made to analyze 2 cohorts as part of this study given the limited numbers of knee replacements in the PROMs database relative to the NJR and HES-APC databases. When the NJR cohort was merged with the HES-APC dataset this was used to create Cohort 1 to compare implant-related outcomes (revision, reoperation, complications). The merged NJR HES-APC unmatched dataset was also merged with the HES-PROMs dataset to create Cohort 2 to compare PROMs.

Outcome measures

Outcomes of interest were: 1) revision rate, 2) indications for revision surgery, 3) reoperation rate, 4) 3-month medical complication rate, and 5) 6-month Oxford Knee Score and EQ-5D score. UKRs were compared from 3 surgeon caseloads: low (< 10 UKRs/year), medium (10 to < 30 UKRs/year), and high (≥ 30 UKRs/year) with TKRs. For subgroup analyses, 8-year revision/reoperation rates are presented, given the limited numbers in the UKR group at 10 years.

Data linkage

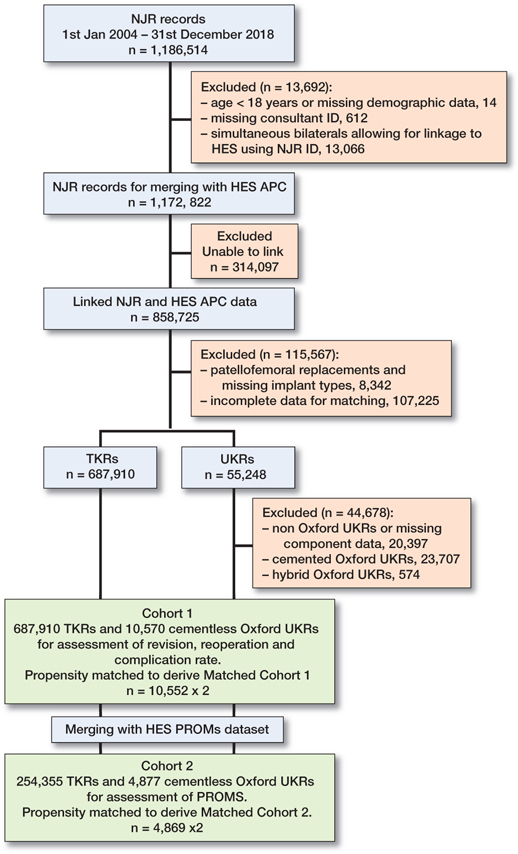

Datasets were linked using pseudo-anonymised identification numbers. 858,725 NJR records were linked to the HES-APC and after data cleaning (Figure 1) there were 10,570 cementless UKRs and 687,910 TKRs. This was used to derive Cohort 1. The same cohort was merged with HES-PROMs and Cohort 2 derived (Figure 1). Cases were excluded if either no preoperative anxiety score was available or there was not both a preoperative and postoperative OKS.

Figure 1. Data flowchart of dataset cleaning and merging.

Statistics

There were statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between cementless Oxford UKR and TKR groups in both Cohorts 1 and 2 (Tables 1 and 5, see Supplementary data). We a priori matched groups for known confounders using propensity scores.

Logistic regression was used to generate propensity scores, representing the probability that a patient received a cementless UKR. All covariates in Table 1 (see Supplementary data) were used and caseload calculated as previously described (7,18). BMI was not used for matching given the significant proportion of missing data as mentioned previously (19-22). We did not use an imputation model for missing BMI data as this does not contribute bias if the reasons for the missing data are unrelated to clinical outcomes. There is no evidence to suggest that BMI is missing from patients with different clinical outcomes as this information is collected at the time of primary surgery on the NJR data collection forms. Cohort 2 was also matched on preoperative anxiety and preoperative OKS to allow fair comparison of PROMs (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

The algorithm used greedy matching at a 1:1 ratio on the logit of the propensity score with a 0.02-SD calliper width (23). Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were examined both before and after matching to assess for any covariate imbalance (SMDs ≥ 10%) (24). After matching, 10,552 cementless UKRs and 10,552 TKRs were included for analysis for Matched Cohort 1 and 4,869 cementless UKRs and 4,869 TKRs for Matched Cohort 2.

Cumulative survival was determined using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Separate calculations were made for the 2 ‘implant survival’ endpoints—revision surgery (any implant component removed, exchanged, or added) and reoperation surgery (any additional surgery including revision). Implant and patient survival rates were compared using Cox regression models. The hazard ratios (HR) represent the risk of the event occurring in the cementless UKR group compared with the TKR group. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. If the proportional hazards assumption was violated, we analyzed survival hazards in sections, with breaks being placed at the points of divergence from proportionality. To account for clustering within the matched cohort, a cluster robust variance estimator was used in regression models. The cluster identifier was the matched sets. A multi-level frailty model sensitivity analysis was performed to control for patient clustering within surgeons, but this did not influence the results. Adjusted models were tested including covariates with residual imbalance after matching (SMD ≥ 10%). As a sensitivity analysis we included available BMI data as a covariate in the Cox regression models but this did not influence any of the results presented.

Medical complications were defined as a stroke, myocardial infarction, chest infection, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (DVT/PE), urinary tract infection (UTI), acute renal failure, or blood transfusion. The frequency of revisions for specific indications and 3-month medical complications between the TKR and cementless UKR groups was compared by the chi-square test except when frequencies were 5 or below, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used.

The mean OKS is presented as an overall score between 0 and 48 (13) and proportion attaining excellent (≥ 41), good (34–41), fair (27–33), and poor (< 27) results (25). EQ-5D comprises five questions concerning mobility, selfcare, activities of daily living, pain, and anxiety/depression and is presented as an overall index from 1 (perfect health) to –0.594 (worst possible state) (14,26).

Given PROMs scores were not normally distributed, appropriate nonparametric tests were used. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare pre- and postoperative scores and the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare TKR and cementless UKR scores.

All analyses were performed using Stata (Version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Ethical approval was obtained from the South Central Oxford-B Research Ethics Committee (Reference:19/SC/0292) and dataset linkage approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (Reference:19/CAG/0054). Financial support has been received from Zimmer Biomet but this played no role in the design, conduct, or writing of the study.

Results

Between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2018, 1,186,514 knee replacements were performed. 858,725 records were linked to the HES-APC records. After removing patellofemoral replacements, missing implant types, and non-Oxford UKRs there were 10,570 cementless Oxford UKRs and 687,910 TKRs for matching (Figure 1, Cohort 1).

This unmatched cohort was matched to form Matched Cohort 1. The same unmatched cohort was also merged with the HES-PROMs dataset and was matched to form Matched Cohort 2 (Figure 1).

Matched Cohort 1 results

There were differences in baseline characteristics between UKR and TKR groups (Table 1, see Supplementary data). The matched study group consisted of 10,552 cementless UKRs and 10,552 TKRs and was well balanced except for minor differences in surgery year (Table 1, see Supplementary data). The mean follow-up for both groups was 3.3 years (SD 2.2).

Revision endpoint

In the cementless UKR and TKR groups there were 327 revisions and 210 revisions respectively. Overall, the rates of implant survival for cementless UKR and TKR at 10 years were 92% (CI 89–94) and 95% (CI 93–96), with HR of 1.5 (CI 1.3–1.8).

Subgroup analyses of UKR caseloads low (n = 1,736), medium (n = 4,456), and high (n = 4,360) had 8-year implant survivals of 90% (CI 87–93), 93% (CI 91–95), and 96% (CI 94–97) respectively. At 8 years TKR survival was 96% (CI 95–97) (Figure 2). The respective HRs for the different UKR caseload groups compared with their matched TKRs were 2.0 (CI 1.3–2.9), 2.0 (CI 1.6–2.7), and 1.0 (CI 0.8–1.3) (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the TKR groups (p = 0.2).

Figure 2. 8-year cumulative revision and reoperation rates of cementless Oxford UKRs and TKRs across different UKR caseloads.

The rates of revision for osteoarthritis progression, dislocation/subluxation, component dissociation, malalignment, periprosthetic fracture, and other were statistically significantly higher following cementless UKR, but the rates of revision for infection and stiffness were statistically significantly lower (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Reoperation endpoint

In the UKR group and TKR group there were 1,022 and 1,195 reoperations respectively.

The 10-year reoperation survival was 77% (CI 73–81) for cementless UKR and 78% (CI 76–81) for TKR. The HR for reoperation was 0.8 (CI 0.7–0.9) and varied with time. From 0 to 5 years cementless UKR was superior, with an HR of 0.8 (CI 0.7–0.9). From 5 to 10 years there were no significant differences between groups with an HR of 1.1 (CI 0.8–1.6).

Subgroup analyses of UKR caseloads low (n = 1,736), medium (n = 4,456), and high (n = 4,360) had 8-year reoperation survivals of 76% (CI 71–80), 81% (CI 78–85), and 84% (CI 82–86) respectively (Figure 2). At 8 years, TKR survival was 81% (CI 80–83). The respective HRs for the different caseload groups compared with their matched TKR were 1.2 (CI 1.0–1.4), 0.9 (CI 0.8–1.0), and 0.6 (CI 0.5–0.7) (Table 2). No differences were found between the reoperation survival in the TKR groups (p = 0.4).

3-month medical complications

The risk of medical complications was significantly lower following cementless UKR (2.6% vs. 4.3%, p < 0.001, Table 4). The rates of chest infection (0.9% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.006), deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (0.3% vs. 0.6%, p = 0.001), urinary tract infection (0.7% vs. 1.0%, p = 0.03), acute kidney injury (0.9% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.006), and blood transfusion (0.03% vs. 0.6%, p < 0.001) were lower for UKR.

| 3-month complications (HES records) | Cementless | ||

| TKR n = 10,552 | UKR n = 10,552 | p-value a | |

| Medical complications | 456 (4.3) | 279 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 6 (0.06) | 6 (0.06) | 1.0 |

| Chest infection | 131 (1.2) | 90 (0.9) | 0.006 |

| Myocardial infarction | 14 (0.13) | 6 (0.06) | 0.1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | 62 (0.6) | 29 (0.3) | 0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 104 (1.0) | 75 (0.7) | 0.03 |

| Acute renal failure | 137 (1.3) | 95 (0.9) | 0.006 |

| Blood transfusion | 65 (0.6) | 3 (0.03) | < 0.001 |

| a Rates were compared between groups using the chi-square test except when frequencies were below 5, in which case Fisher’s exact test was utilized. | |||

Matched Cohort 2 results

There were significant differences in baseline characteristics between UKR and TKR groups (Table 5, see Supplementary data). The matched study group consisted of 4,869 cementless UKRs and 4,869 TKRs and was well balanced except from minor differences in surgery year (Table 5, Supplementary data). The numbers of cementless UKRs in caseload groups low, medium, and high were 685, 2,005, and 2,179 respectively.

OKS comparison

The mean preoperative OKS for the TKR and cementless UKR groups were 21 (SD 7.8) and 21 (SD 7.6) (p = 0.3). Both groups showed a statistically significant improvement in their 6-month postoperative scores (p < 0.001) to 37 (SD 9.2) and 39 (SD 8.8) respectively. The cementless UKR group had a statistically significantly higher (p < 0.001) 6-month postoperative score by 2.1 points. The TKR group gained 16 points (SD 9.8) postoperatively whereas the UKR group gained 18 points (SD 9.6), with the difference being statistically significant (p < 0.001). The UKR group had a greater proportion of postoperative excellent scores (52% vs 39%, p < 0.001) and a lower proportion of postoperative poor scores (10% vs. 14%, p < 0.001) compared with TKR (Table 6).

| OKS categorization | TKR (n = 4,869) | UKR (n = 4,869) | p-value a |

| Preoperative | |||

| Poor | 3,656 (75) | 3,648 (75) | 0.9 |

| Fair | 906 (19) | 941 (19) | 0.5 |

| Good | 284 (5) | 260 (5) | 0.3 |

| Excellent | 23 (1) | 20 (1) | 0.7 |

| Postoperative | |||

| Poor | 681 (14) | 501 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Fair | 728 (15) | 517 (11) | < 0.001 |

| Good | 1,552 (32) | 1,315 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Excellent | 1,908 (39) | 2,536 (52) | < 0.001 |

| a Rates were compared between groups using the chi-square test. | |||

Subgroup analysis of OKS in the UKR caseload groups low, medium, and high showed 6-month scores of 38 (SD 9.2), 39 (SD 9.1), and 40 (SD 8.2) respectively. All scores were higher than for TKR (p < 0.001).

EQ-5D comparison

The mean preoperative EQ-5D index for the TKR and UKR groups was 0.47 (SD 0.30) and 0.48 (SD 0.29) respectively with no significant differences (p = 0.1). Both groups showed an improvement in their 6-month scores (p < 0.001) to 0.77 (SD 0.24) and 0.80 (SD 0.23) respectively. The 6-month EQ-5D for the cementless UKR was higher than TKR (p < 0.001). The TKR group gained 0.31 (SD 0.32) points postoperatively whereas the UKR group gained 0.30 (SD 0.32) (p < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis of EQ-5D in the UKR caseload groups low, medium, and high showed 6-month scores of 0.78 (SD 0.24), 0.79 (SD 0.24), and 0.82 (SD 0.22) respectively. The EQ-5D for the UKR in all caseload groups was higher than that of TKR, however in the low caseload group the difference was not significant (p = 0.06) whereas in the medium and high caseload groups it was (p < 0.001.

Discussion

This is the first study that has compared the long-term outcomes of matched cementless UKRs and TKRs. UKRs had higher revision rates (HR 1.5) but lower reoperation rates (HR 0.83). UKR results were influenced by surgeon caseload: high-volume UKR surgeons had similar UKR revision rates to TKR (HR 1.0) but much lower reoperation rates (HR 0.6). Medium-volume UKR surgeons had higher UKR revision rates than TKR (HR 2.0) but similar reoperation rates (HR 0.9). Low-volume UKR surgeons had higher UKR revision (HR 2.0) and reoperation (HR 1.2) rates than TKR.

The 10-year revision survival of the matched cementless Oxford UKR cohort was 92%. This achieves a 10A ODEP (Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel) rating (27). Unmatched registry data shows that UKR revision rates are several times higher than TKR (4-6). However, in this matched study the overall revision rate of the cementless UKR is only 1.5 times (HR) higher and may partially be explained by a lower threshold for revision for UKR (28). UKR revisions were commonly arthritis progression and dislocation/dissociation/instability, which can easily be treated with bearing replacement, lateral UKR, or simple conversion to primary TKR with good results. In contrast the commonest reasons for TKR revision were infection, which occurred more frequently than after UKR, and loosening. These revisions tend to be complex, requiring revision knee replacement components and possibly 2 stages. Patients are concerned about having further surgery and not whether it is defined as a revision. Therefore, they would probably favor a cementless UKR over a TKR as the reoperation rate is lower (HR 0.83) despite the revision rate being higher.

Previous studies that have shown UKR revision rate is influenced by surgeon caseload (7,18), but this is the first study to compare the difference UKR caseload results against matched TKRs. As part of the matching, we ensured surgeons implanting the UKR did the same number of knee replacements annually as those implanting the matched TKR. We found that the high-volume UKR surgeons had a UKR revision rate similar to TKR and lower reoperation rate. These surgeons should be encouraged to continue doing UKR. In contrast, low-volume UKR surgeons had higher revision and reoperation rates with UKR than TKR. These surgeons should consider either stopping doing UKR or perhaps changing their indications to do more. The indications for the cementless Oxford UKR are satisfied in up to 50% of knee replacements (29), so providing they are doing at least 2 knee replacements per month they should be able to increase their UKR so as to be doing at least 10 per year. The middle UKR caseload group seem to achieve acceptable results, as their UKR reoperation rate is similar to that of TKR even though the revision rate is higher. This mid-caseload group should also ensure they are adhering to the recommended indications. It is perhaps counterintuitive that doing a higher proportion of knee replacements as UKR decreases the revision rate. The reason for this is probably that surgeons with very narrow indications tend to use UKR for early arthritis, when they do not want to do a TKR, and in this situation the revision rate is high. In contrast, if the recommended indications are adhered to and the device is used in severe arthritis, as an alternative to TKR, the revision rate is low (30).

The 6-month postoperative OKS of cementless Oxford UKR was statistically significantly higher than TKR in all caseload groups, with the largest difference, of 3 points, being in the high caseload group. The average difference was 2 points, which is similar to the TOPKAT randomized control trial (31). Although the magnitude of the difference is below the suggested MCID (13), the skewed nature of the OKS with the ceiling effect does not mean that the difference is unimportant. Furthermore, the UKR had 13% more excellent OKS results and 4% less poor results than TKR. This study has also shown that the cementless Oxford UKR offers better 6-month quality of life with EQ-5D. This is close to the lower limit of MCID for the EQ-5D index (32). Our study has shown rates of postoperative medical complications were about 60% higher following TKR than cementless UKR, which is similar to Liddle (1).

Our study strengths include that it is an unselected registry sample recruited over an extended period. By data linkage various clinical outcomes were assessed. Propensity matching allowed comparison of similar population cohorts. However, it is retrospective and based on observational data. Matching can reduce the generalizability of findings, but we were able to match almost all the cementless Oxford UKRs to TKRs. Given missing BMI data, we did not match on BMI. The PROMs dataset provides only postoperative scores at 6 months. However, most improvement in PROMs after joint replacement occurs in the first 6 months and is thereafter generally static (15-17,33). Finally, we could only match using database variables, meaning there could be unaccounted variables, which could lead to residual confounding.

In conclusion, the cementless Oxford UKR had lower rates of medical complications and better functional outcomes than TKR. It also showed that the revision and reoperation rate depended on the surgeon’s UKR caseload: With low-volume UKR surgeons the revision and reoperation rates are higher for UKR than TKR. For mid-volume UKR surgeons the reoperation rate is similar but the revision rate higher. For high-volume surgeons the reoperation rates are lower for the UKR and there is no differences in revision rates. Surgeons keen to do UKR should reflect on their indications for UKR so as to ensure they are in the mid- or ideally the high-volume group.

- Liddle A D, Judge A, Pandit H, Murray D W. Adverse outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee replacement in 101 330 matched patients: a study of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet 2014; 384: 1437-45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60419-0.

- Liddle A, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray D. Patient-reported outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study of 14 076 matched patients from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Bone Joint J 2015; 97: 793-801. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B6.35155.

- Burn E, Liddle A D, Hamilton T W, Judge A, Pandit H G, Murray D W, et al. Cost-effectiveness of unicompartmental compared with total knee replacement: a population-based study using data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. BMJ Open 2018; 8(4): e020977. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020977.

- Australian Orthopaedic Association. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, knee & shoulder arthroplasty; 2019.

- National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry 15th Annual Report. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Isle of Man; 2018.

- New Zealand Joint Registry. Twenty year report January 1999 to December 2018. New Zealand Joint Registry; 2019.

- Liddle A D, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray D W. Effect of surgical caseload on revision rate following total and unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Surg Am 2016; 98: 1-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00487.

- Goodfellow J, O’Connor J, Murray D. A critique of revision rate as an outcome measure: re-interpretation of knee joint registry data. Bone Joint J 2010; 92: 1628-31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25193.

- Mohammad H R, Strickland L, Hamilton T W, Murray D W. Long-term outcomes of over 8,000 medial Oxford Phase 3 Unicompartmental Knees: a systematic review. Acta Orthop 2018; 89: 101-7. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1367577.

- Mohammad H R, Kennedy J A, Mellon S J, Judge A, Dodd C A, Murray D W. Ten-year clinical and radiographic results of 1000 cementless Oxford unicompartmental knee replacements. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020; 28(5): 1479-87. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05544-w.

- NHS Digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity 2019–20. NHS Digital. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/2019-20 (Accessed October 4, 2020).

- NHS Digital. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). NHS Digital; 2020. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/patient-reported-outcome-measures-proms (Accessed October 4, 2020).

- Murray D, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard D, Carr A, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. Bone Joint J 2007; 89: 1010-14. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19424.

- Group T E. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199-208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9.

- Browne J P, Bastaki H, Dawson J. What is the optimal time point to assess patient-reported recovery after hip and knee replacement? A systematic review and analysis of routinely reported outcome data from the English patient-reported outcome measures programme. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 128. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-128.

- Williams D, Blakey C, Hadfield S, Murray D, Price A, Field R. Long-term trends in the Oxford knee score following total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95: 45-51. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.28573.

- Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill H, Barker K, Dodd C, Murray D. Minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: results of 1000 cases. Bone Joint J 2011; 93: 198-204. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B2.25767.

- Mohammad H R, Matharu G S, Judge A, Murray D W. The effect of surgeon caseload on the relative revision rate of cemented and cementless unicompartmental knee replacements: an analysis from the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2020; 102(8): 644-53. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01060.

- Matharu G S, Judge A, Murray D W, Pandit H G. Trabecular metal acetabular components reduce the risk of revision following primary total hip arthroplasty: a propensity score matched study from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Arthroplasty 2017; 33(2): 447-52. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.036.

- Matharu G S, Judge A, Murray D W, Pandit H G. Outcomes after metal-on-metal hip revision surgery depend on the reason for failure: a propensity score-matched study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018; 476: 245-58. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000029.

- Mohammad H R, Matharu G S, Judge A, Murray D W. A matched comparison of revision rates of cemented Oxford Unicompartmental Knee Replacements with Single and Twin Peg femoral components, based on data from the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Acta Orthop 2020; 91(4): 420-5. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1748288.

- Mohammad H R, Matharu G S, Judge A, Murray D W. Comparison of the 10-year outcomes of cemented and cementless unicompartmental knee replacements: data from the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Acta Orthop 2020; 91: 76-81. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2019.1680924.

- Austin P C. Some methods of propensity–score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulations. Biom J 2009; 51: 171-84. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810488.

- Austin P C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity–score matched samples. Stat Med 2009; 28: 3083-107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697.

- Kalairajah Y, Azurza K, Hulme C, Molloy S, Drabu K J. Health outcome measures in the evaluation of total hip arthroplasties: a comparison between the Harris hip score and the Oxford hip score. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20: 1037-41. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.017.

- Devlin N J, Parkin D, Browne J. Patient–reported outcome measures in the NHS: new methods for analysing and reporting EQ–5D data. Health Econ 2010; 19: 886-905. doi: 10.1002/hec.1608.

- ODEP. Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel. https://www.odep.org.uk/; 2022 (Accessed November 14, 2021).

- Goodfellow J, O’Connor J, Murray D. A critique of revision rate as an outcome measure: re-interpretation of knee joint registry data. Bone Joint J 2010; 92: 1628-31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25193.

- Willis-Owen C A, Brust K, Alsop H, Miraldo M, Cobb J. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty in the UK National Health Service: an analysis of candidacy, outcome and cost efficacy. Knee 2009; 16: 473-8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.04.006.

- Kennedy J A, Palan J, Mellon S J, Esler C, Dodd C A, Pandit H G, et al. Most unicompartmental knee replacement revisions could be avoided: a radiographic evaluation of revised Oxford knees in the National Joint Registry. Knee Surg, Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc 2020; 28(12): 3926-34. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-05861-5.

- Beard D J, Davies L J, Cook J A, MacLennan G, Price A, Kent S, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of total versus partial knee replacement in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis (TOPKAT): 5-year outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 746-56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31281-4.

- Coretti S, Ruggeri M, McNamee P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: a critical review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2014; 14: 221-33. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.894462.

- Breeman S, Campbell M, Dakin H, Fiddian N, Fitzpatrick R, Grant A, et al. Five-year results of a randomised controlled trial comparing mobile and fixed bearings in total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95: 486-92. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B4.29454.

Supplementary data

| Covariate | Unmatched cohort | SMD | Matched cohort | SMD | ||

| TKR n = 687,910 | UKR n = 10,570 | TKR n = 10,552 | UKR n = 10,552 | |||

| Admission type | ||||||

| Elective | 686,359 (100) | 10,562 (100) | 0.04 | 10,546 (100) | 10,544 (100) | 0.02 |

| Emergency | 1,145 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | ||

| Other | 406 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 397,580 (58) | 4,824 (46) | 0.25 | 4,781 (45) | 4,821 (46) | 0.008 |

| Male | 290,330(42) | 5,746 (54) | 5,771 (55) | 5,731 (54) | ||

| Age at surgery, mean (SD) | 70.2 (9.3) | 65.2 (9.5) | 0.53 | 65.5 (9.3) | 65.2 (9.5 | 0.03 |

| BMI, mean (SD) a | 31.0 (5.5) | 30.7 (5.3) | 0.07 | 31.3 (5.4) | 30.7 (5.3) | 0.1 |

| n | 450,147 | 9,081 | 8,429 | 9,065 | ||

| Primary diagnosis | ||||||

| Primary OA | 660,579 (96) | 10,407 (98) | 0.15 | 10,393 (98) | 10,389 (98) | 0.01 |

| Primary OA and other | 8,032 (1) | 52 (1) | 58 (1) | 52 (1) | ||

| Other | 19,299 (3) | 111 (1) | 101 (1) | 111 (1) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| None | 479,655 (70) | 7,322 (69) | 0.04 | 7,264 (69) | 7,308 (69) | 0.02 |

| Mild | 146,567 (21) | 2,201 (21) | 2,248 (21) | 2,198 (21) | ||

| Moderate | 41,999 (6) | 754 (7) | 722 (7) | 753 (7) | ||

| Severe | 19,689 (3) | 293 (3) | 318 (3) | 293 (3) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 647,039 (94) | 10,166 (96) | 0.12 | 10,150 (96) | 10,148 (96) | 0.02 |

| Black (Caribbean) | 4,786 (1) | 42 (0) | 37 (0) | 42 (0) | ||

| Black (African) | 2,935 (0) | 23 (0) | 23 (0) | 23 (0) | ||

| Black (other) | 1,217 (0) | 11 (0) | 6 (0) | 11 (0) | ||

| Indian | 16,623 (3) | 145 (2) | 147 (2) | 145 (2) | ||

| Pakistani | 6,132 (1) | 46 (1) | 48 (1) | 46 (1) | ||

| Bangladeshi | 492 (0) | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 2 (0) | ||

| Chinese | 516 (0) | 3 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 (0) | ||

| Other | 8,170 (1) | 132 (1) | 137 (1) | 132 (1) | ||

| Rural/urban classification | ||||||

| Urban | 520,413 (76) | 7,148 (68) | 0.13 | 7,206 (68) | 7,140 (68) | 0.01 |

| Town/fringe | 80,040 (11) | 1,400 (13) | 1,377 (13) | 1,397 (13) | ||

| Village/hamlet | 87,457 (13) | 2,022 (19) | 1,969 (19) | 2,015 (19) | ||

| Indices of multiple deprivation (quintiles) | ||||||

| 1 | 107,839 (16) | 852 (8) | 0.33 | 857 (8) | 852 (8) | 0.02 |

| 2 | 129,418 (19) | 1,518 (14) | 1,522 (14) | 1,518 (14) | ||

| 3 | 151,737 (22) | 2,304 (22) | 2,329 (22) | 2,301 (22) | ||

| 4 | 156,380 (22) | 2,570 (24) | 2,607 (25) | 2,568 (24) | ||

| 5 | 142,536 (21) | 3,326 (32) | 3,237 (31) | 3,313 (32) | ||

| Surgeon caseload of primary knee surgery practice (cases/year) | ||||||

| mean (SD) | 76.6 (47.4) | 95.3 (45.8) | 0.40 | 94.7 (54.5) | 95.1 (45.7) | 0.009 |

| Primary complexity | ||||||

| Normal | 684,951 (100) | 10,570 (100) | 0.09 | 10,552 (100) | 10,552 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Complex | 2,959 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| ASA grade | ||||||

| 1 | 63,179 (9) | 1,744 (17) | 0.28 | 1,628 (16) | 1,729 (16) | 0.03 |

| 2 | 497,045 (72) | 7,619 (72) | 7,730 (73) | 7,616 (72) | ||

| 3 or above | 127,686 (19) | 1,207 (11) | 1,194 (11) | 1,207 (12) | ||

| VTE—chemical prophylaxis | ||||||

| LMWH (± other) | 486,575 (71) | 8,158 (77) | 0.29 | 8,134 (77) | 8,143 (77) | 0.02 |

| Aspirin only | 47,054 (7) | 553 (5) | 537 (5) | 550 (5) | ||

| Other | 118,183 (17) | 1,785 (17) | 1,819 (17) | 1,785 (17) | ||

| None | 36,098 (5) | 74 (1) | 62 (1) | 74 (1) | ||

| VTE—mechanical prophylaxis | ||||||

| Any | 635,845 (92) | 10,417 (99) | 0.30 | 10,411 (99) | 10,399 (99) | 0.01 |

| None | 52,065 (8) | 153 (1) | 141 (1) | 153 (1) | ||

| Year of surgery | ||||||

| 2004 | 11,303 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.01 | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| 2005 | 16,637 (2) | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2006 | 22,196 (3) | 15 (0) | 6 (0) | 15 (0) | ||

| 2007 | 32,943 (5) | 15 (0) | 28 (0) | 15 (0) | ||

| 2008 | 39,206 (6) | 25 (0) | 66 (0) | 25 (0) | ||

| 2009 | 43,393 (6) | 107 (1) | 112 (1) | 107 (1) | ||

| 2010 | 48,984 (7) | 202 (2) | 187 (2) | 202 (2) | ||

| 2011 | 52,247 (8) | 320 (3) | 274 (3) | 320 (3) | ||

| 2012 | 54,113 (8) | 468 (5) | 408 (4) | 468 (5) | ||

| 2013 | 55,217 (8) | 590 (6) | 611 (6) | 590 (6) | ||

| 2014 | 60,156 (9) | 936 (9) | 885 (8) | 936 (9) | ||

| 2015 | 61,173 (9) | 1,300 (12) | 1,234 (12) | 1,300 (12) | ||

| 2016 | 64,241 (9) | 1,927 (18) | 1,753 (17) | 1,927 (18) | ||

| 2017 | 66,040 (10) | 2,321 (22) | 2,267 (21) | 2,318 (22) | ||

| 2018 | 60,061 (9) | 2,344 (22) | 2,711 (26) | 2,329 (22) | ||

| Bone graft | ||||||

| None | 679,574 (99) | 10,520 (100) | 0.08 | 10,493 (99) | 10,552 (99) | 0.01 |

| Bone graft used | 8,336 (1) | 50 (0) | 59 (1) | 50 (1) | ||

| a All factors were used for matching except BMI. | ||||||

| Revision indication | TKR n (%) | Years to TKR revision mean (SD) | Cementless UKR n (%) | Years to UKR revision mean (SD) | p-value a |

| Aseptic loosening | 44 (0.4) | 2.7 (1.7) | 32 (0.3) | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.2 |

| OA progression | 16 (0.2) | 2.9 (2.6) | 86 (0.8) | 3.8 (2.3) | < 0.001 |

| Pain | 33 (0.3) | 2.2 (1.6) | 40 (0.4) | 2.4(1.7) | 0.4 |

| Other | 26 (0.3) | 1.5 (1.2) | 43 (0.4) | 2.1 (1.9) | 0.04 |

| Dislocation subluxation revision | 4 (0) | 1.2 (0.7) | 45 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Instability | 29 (0.3) | 1.9 (1.4) | 39 (0.4) | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.2 |

| Component dissociation | 0 (0) | N/A | 18 (0.2) | 1.5 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Malalignment | 13 (0.1) | 2.6 (0.9) | 29 (0.3) | 1.7 (1.3) | 0.01 |

| Infection | 56 (0.5) | 1.6 (1.7) | 28 (0.3) | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.002 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 3 (0) | 0.5 (0.3) | 31 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Lysis | 9 (0.1) | 2.8 (1.4) | 6(0.1) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.6 |

| Wear | 4 (0) | 1.9 (2.0) | 8 (0.1) | 3.0 (2.4) | 0.4 |

| Stiffness | 22 (0.2) | 1.9 (1.2) | 5 (0.1) | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.002 |

| Implant fracture | 2 (0) | 3.2 (2.3) | 1 (0) | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Incorrect sizing | 0 (0) | N/A | 0 (0) | N/A | No revisions |

| a Comparisons between the frequency of revision indications were conducted using the chi-square test unless the frequencies were below 5 in which Fisher’s exact test was utilized. | |||||

| The mean time to each revision indication was calculated from the differences in time from the primary operation and revision surgery for the revised cases for each revision indication specified. | |||||

| Covariate | Unmatched cohort | SMD | Matched cohort | SMD | ||

| TKR n = 254,355 | UKR n = 4,877 | TKR n = 4,869 | UKR n = 4,869 | |||

| Admission type | ||||||

| Elective | 254,178 (100) | 4,873 (100) | 0.01 | 4,868 (100) | 4,865 (100) | 0.03 |

| Emergency | 163 (0) | 4 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (0) | ||

| Other | 14 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 145,049 (57) | 2,201 (45) | 0.24 | 2,175 (45) | 2,199 (45) | 0.01 |

| Male | 109,306 (43) | 2,676 (55) | 2,694 (55) | 2,670 (55) | ||

| Age at surgery, mean (SD) | 70.2 (8.8) | 66.0 (9.0) | 0.47 | 66.1 (8.6) | 66.0 (9.0) | 0.007 |

| BMI, mean (SD) a | 30.9 (5.4) | 30.4 (5.0) | 0.10 | 30.8 (5.1) | 30.4 (5.0) | 0.09 |

| n | 192,787 | 4,225 | 3,946 | 4,217 | ||

| Primary diagnosis: | ||||||

| Primary OA | 246,026 (97) | 4,799 (98) | 0.11 | 4,783 (98) | 4,791 (98) | 0.01 |

| Primary OA and other | 2,645 (1) | 21 (1) | 25 (1) | 21 (1) | ||

| Other | 5,684 (2) | 57 (1) | 61 (1) | 57 (1) | ||

| Preoperative Oxford Knee Score | ||||||

| mean (SD) | 18.9 (7.7) | 21.3 (7.7) | 0.32 | 21.2 (7.8) | 21.3 (7.6) | 0.02 |

| Preoperative anxiety/depression status | ||||||

| Not anxious/depressed | 160,604 (63) | 3,293 (67) | 0.10 | 3,292 (67) | 3,286 (67) | 0.006 |

| Moderately | 83,970 (33) | 1,451 (30) | 1,440 (30) | 1,450 (30) | ||

| Extremely | 9,781 (4) | 133 (3) | 137 (3) | 133 (3) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| None | 177,003 (70) | 3,390 (69) | 0.03 | 3,428 (70) | 3,382 (69) | 0.02 |

| Mild | 54,018 (21) | 1,004 (21) | 970 (20) | 1,004 (21) | ||

| Moderate | 16,160 (6) | 340 (7) | 340 (7) | 340 (7) | ||

| Severe | 7,174 (3) | 143 (3) | 131 (3) | 143 (3) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 243,425 (96) | 4,754 (98) | 0.12 | 4,760 (98) | 4,746 (98) | |

| Black (Caribbean) | 1,291 (0) | 16 (0) | 18 (0) | 16 (0) | 0.03 | |

| Black (African) | 849 (0) | 6 (0) | 4 (0) | 6 (0) | ||

| Black (other) | 379 (0) | 7 (0) | 5 (0) | 7 (0) | ||

| Indian | 4,499 (2) | 47 (1) | 44 (1) | 47 (1) | ||

| Pakistani | 1,280 (1) | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | ||

| Bangladeshi | 113 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Chinese | 175 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 2,344 (1) | 39 (1) | 30 (1) | 39 (1) | ||

| Rural/urban classification | ||||||

| Urban | 187,601 (74) | 3,176 (65) | 0.21 | 3,131 (64) | 3,172 (65) | 0.03 |

| Town/fringe | 31,579 (12) | 679 (14) | 718 (15) | 677 (14) | ||

| Village/hamlet | 35,175 (14) | 1,022 (21) | 1,020 (21) | 1,020 (21) | ||

| Indices of multiple deprivation (quintiles) | ||||||

| 1 | 34,627 (14) | 308 (6) | 0.35 | 315 (7) | 308 (6) | 0.02 |

| 2 | 45,285 (18) | 632 (13) | 650 (13) | 632 (13) | ||

| 3 | 56,721 (22) | 1,073 (22) | 1,041 (21) | 1,073 (22) | ||

| 4 | 60,782 (24) | 1,206 (25) | 1,221 (25) | 1,206 (25) | ||

| 5 | 56,940 (22) | 1,658 (34) | 1,642 (34) | 1,650 (34) | ||

| Surgeon caseload of primary knee surgery practice (cases/year) | ||||||

| mean (SD) | 80.5 (48.2) | 98.4 (45.7) | 0.38 | 98.6 (56.9) | 98.3 (45.6) | 0.006 |

| Primary complexity | ||||||

| Normal | 254,328 (100) | 4,877 (100) | 0.02 | 4,869 (100) | 4,869 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Complex | 27 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| ASA grade | ||||||

| 1 | 22,257 (9) | 826 (17) | 0.28 | 846 (17) | 819 (17) | 0.03 |

| 2 | 190,181 (75) | 3,531 (72) | 3,538 (73) | 3,530 (72) | ||

| 3 or above | 41,917 (16) | 520 (11) | 485 (10) | 520 (11) | ||

| VTE—chemical prophylaxis | ||||||

| LMWH (± other) | 179,562 (71) | 3,709 (76) | 0.18 | 3,672 (75) | 3,703 (76) | 0.02 |

| Aspirin only | 12,338 (5) | 227 (5) | 241 (5) | 226 (5) | ||

| Other | 55,739 (22) | 907 (18) | 924 (19) | 906 (18) | ||

| None | 6,716 (2) | 34 (1) | 32 (1) | 34 (1) | ||

| VTE—mechanical prophylaxis | ||||||

| Any | 242,433 (95) | 4,820 (99) | 0.21 | 4,812 (99) | 4,812 (99) | < 0.001 |

| None | 11,922 (5) | 57 (1) | 57 (1) | 57 (1) | ||

| Year of surgery | ||||||

| 2008 | 6 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.75 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| 2009 | 14,106 (5) | 34 (1) | 42 (1) | 34 (1) | ||

| 2010 | 22,414 (9) | 81 (2) | 97 (2) | 81 (2) | ||

| 2011 | 24,678 (9) | 120 (2) | 157 (3) | 120 (3) | ||

| 2012 | 24,922 (10) | 213 (4) | 209 (4) | 213 (4) | ||

| 2013 | 27,176 (11) | 318 (7) | 297 (6) | 318 (6) | ||

| 2014 | 29,682 (12) | 517 (11) | 442 (9) | 517 (11) | ||

| 2015 | 29,154 (11) | 654 (13) | 664 (14) | 652 (13) | ||

| 2016 | 29,896 (12) | 940 (19) | 872 (18) | 938 (19) | ||

| 2017 | 27,687 (11) | 1,029 (21) | 968 (20) | 1,029 (21) | ||

| 2018 | 24,724 (10) | 971 (20) | 1,121 (23) | 967 (20) | ||

| Bone graft | ||||||

| None | 251,103 (99) | 4,851 (99) | 0.08 | 4,844 (99) | 4,843 (99) | 0.003 |

| Bone graft used | 3,252 (1) | 26 (1) | 25 (1) | 26 (1) | ||

| a All factors were used for matching except BMI. | ||||||