The use of antibiotic-loaded bone cement and systemic antibiotic prophylactic use in 2,971,357 primary total knee arthroplasties from 2010 to 2020: an international register-based observational study among countries in Africa, Europe, North America, and Oceania

Tesfaye H LETA 1-4, Anne Marie FENSTAD 1, Stein Håkon L LYGRE 1,5, Stein Atle LIE 1,6, Martin LINDBERG-LARSEN 7,8, Alma B PEDERSEN 7,9, Annette W-DAHL 10,11, Ola ROLFSON 10,12, Erik BÜLOW 12,13, James A ASHFORTH 14, Liza N VAN STEENBERGEN 15, Rob G H H NELISSEN 15,16, Dylan HARRIES 17, Richard DE STEIGER 18, Olav LUTRO 19, Emmi HAKULINEN 20, Keijo MÄKELÄ 21,22, Jinny WILLIS 23, Michael WYATT 23, Chris FRAMPTON 23, Alexander GRIMBERG 24, Arnd STEINBRÜCK 24, Yinan WU 24, Cristiana ARMAROLI 25, Marco MOLINARI 26, Roberto PICUS 27, Kyle MULLEN 28, Richard ILLGEN 28,29, Ioan C STOICA 30-32, Andreea E VOROVENCI 30,33, Dan DRAGOMIRESCU 30,33, Håvard DALE 1,34, Christian BRAND 35,36, Bernhard CHRISTEN 35,37, Joanne SHAPIRO 38,39, J Mark WILKINSON 38,40, Richard ARMSTRONG 38,39, Kate WOOSTER 38,39, Geir HALLAN 1,34, Jan-Erik GJERTSEN 1,34, Richard N CHANG 41, Heather A PRENTICE 41, Elizabeth W PAXTON 41, and Ove FURNES 1,34

1 The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Haukeland University Hospital, Norway; 2 Faculty of Health Science, VID Specialized University, Norway; 3 Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, USA; 4 Department of Medical Device Surveillance & Assessment, Kaiser Permanente, USA; 5 Department of Occupational Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Norway; 6 Institutes of Dentistry, University of Bergen, Norway; 7 The Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register, Denmark; 8 Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark; 9 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital and Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Denmark; 10 The Swedish Arthroplasty Register, Sweden; 11 Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Division of Orthopedics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; 12 Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; 13 Centre of Registers Västra Götaland, Gothenburg, Sweden; 14 JointCare Registry, South Africa; 15 The Dutch Arthroplasty Register, the Netherlands; 16 Department of Orthopedics, Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands; 17 South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Australia; 18 The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry, Australia; 19 Department of Medicine, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway; 20 The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland; 21 The Finnish Arthroplasty Register, Finland; 22 Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland; 23 The New Zealand Joint Registry, New Zealand; 24 The Germany Arthroplasty Registry, Germany; 25 Arthroplasty Registry of the Autonomous Province of Trento (PATN), Clinical Epidemiology Service, Provincial Agency for Health Services of Trento (APSS), Italy; 26 Orthopedics and Traumatology Operative Unit, Cavalese Hospital, Provincial Agency for Health Services of Trento (APSS), Italy; 27 Arthroplasty Register of Autonomous Province of Bolzano (PABZ), Observatory of Health, Health Department AP of Bolzano, Italy; 28 American Joint Replacement Registry, USA; 29 University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, USA; 30 Romanian Arthroplasty Registry, Romania; 31 University of Medicine and Pharmacy – Carol Davila – Bucharest – UMFCD Bucharest, Romania; 32 Foisor Orthopedic Hospital, Romania; 33 Economic Cybernetics and Statistics Doctoral School, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Romania; 34 Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Bergen, Norway; 35 Swiss National Hip & Knee Joint Registry, Switzerland; 36 Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, SwissRDL, University of Bern; Switzerland; 37 Articon, Bern, Switzerland; 38 The National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland, The Isle of Man and Guernsey, UK; 39 NEC Software Solutions, Hemel Hempstead, UK; 40 Department of Oncology and Metabolism, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK; 41 Medical Device Surveillance & Assessment, Kaiser Permanente, USA

Background and purpose — Antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALBC) and systemic antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) have been used to reduce periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) rates. We investigated the use of ALBC and SAP in primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Patients and methods — This observational study is based on 2,971,357 primary TKAs reported in 2010–2020 to national/regional joint arthroplasty registries in Australia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Romania, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA. Aggregate-level data on trends and types of bone cement, antibiotic agents, and doses and duration of SAP used was extracted from participating registries.

Results — ALBC was used in 77% of the TKAs with variation ranging from 100% in Norway to 31% in the USA. Palacos R+G was the most common (62%) ALBC type used. The primary antibiotic used in ALBC was gentamicin (94%). Use of ALBC in combination with SAP was common practice (77%). Cefazolin was the most common (32%) SAP agent. The doses and duration of SAP used varied from one single preoperative dosage as standard practice in Bolzano, Italy (98%) to 1-day 4 doses in Norway (83% of the 40,709 TKAs reported to the Norwegian arthroplasty register).

Conclusion — The proportion of ALBC usage in primary TKA varies internationally, with gentamicin being the most common antibiotic. ALBC in combination with SAP was common practice, with cefazolin the most common SAP agent. The type of ALBC and type, dose, and duration of SAP varied among participating countries.

Citation: Acta Orthopaedica 2022; 94: 416–425. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/17453674.2023.17737.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Submitted: 2023-03-27. Accepted: 2023-06-02. Published: 2023-08-09.

Correspondence: tesfaye.hordofa.leta@helse-bergen.no

THL is a principal investigator of this study and drafted the manuscript. THL together with OF initiated the concept of this study. AMF, EWP, OF, HAP, SAL, SHLL, RNC, and THL contributed to the design of this study. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and content of the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published.

The authors are very grateful to all participating registries for their willingness and ability to participate in this study. Their thanks also go to all the orthopedic surgeons in the respective countries of participating registries for reporting their surgical cases to their registries. The authors additionally thank Dr Maria Adalgisa Gentilini for preparing (contributing to the acquisition and analysis) of the PATN-Italy data for the current study.

Handling co-editors: Bart Swierstra and Jonas Ranstam

Acta thanks Marina Torre for help with peer review of this manuscript.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication following joint arthroplasty leading to longer hospital stay, increased risk of readmission, poor patient outcomes and increased cost burden [1,2]. It is a frequent cause of revision after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and its incidence has increased over the last 2 decades [3,4].

In an attempt to reduce the risk of PJI, antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALBC) has been used since it was introduced by Bucholz and Engelbrecht in 1970 [1,5,6]. Debate persists regarding the use of ALBC, its efficacy in reducing revision due to PJI, and whether the effect varies with cement type (brand) and viscosity [7,8].

Similarly, the use of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) is acknowledged as an important part of mitigating PJI [9-11]. However, there is a lack of consensus in practice guidelines on the type of systemic antibiotic, dose (single dose or multiple doses) and duration (0–24, 24–48, or > 48 hours) of SAP internationally [10-12].

We aimed to investigate the use of ALBC and SAP use in primary TKA internationally. Specifically, we investigated the trends in use in the period between 2010 and 2020. The type (brand), viscosity of bone cement, and antibiotics in the cement were investigated for ALBC, and the type of antibiotic agent, dose, and duration for SAP.

Patients and methods

Participating registries

This is an international register-based observational descriptive study reported according to STROBE guidelines [13]. Primary cemented or hybrid TKAs for osteoarthritis (OA) reported to 16 national and regional arthroplasty registries in 14 countries across 4 continents between 2010 and 2020 were included (Table 1).

| Abbreviation | Register | Website |

| AJRR | American Joint Replacement Registry | https://www.aaos.org/registries |

| AOANJRR | Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry | https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/ |

| DKR | Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry | Dansk Knæalloplastikregister - Sundhed.dk |

| EPRD | German Arthroplasty Registry | https://www.eprd.de/ |

| FAR | Finnish Arthroplasty Register | www.thl.fi/far |

| JointCare | JointCare Registry (South Africa) | https://www.joint-care.co.za |

| KP | Kaiser Permanente Total Joint Replacement Registry (USA) | https://national-implantregistries.kaiserpermanente.org/ |

| LROI | Dutch Arthroplasty Register | www.lroi-report.nl |

| NAR | Norwegian Arthroplasty Register | https://helse-bergen.no/nrl |

| NJR | National Joint Registry (UK ) | https://www.njrcentre.org.uk/ |

| NZJR | New Zealand Joint Registry | https://www.nzoa.org.nz/nzoa-joint-registry |

| PABZ | Bolzano provincial register of knee prostheses (Italy) | www.provinz.bz.it/health-lifestyle/healthmonitoring/provincial-arthroplasty-register.asp |

| PATN | Trento provincial register of knee prostheses (Italy) | https://riap.iss.it/riap/it/il-progetto/chi-partecipa/provincia-autonoma-di-trento/ |

| RAR | Romanian Arthroplasty Register | http://www.rne.ro/ |

| SAR | The Swedish Arthroplasty Register | https://sar.registercentrum.se/ |

| SIRIS | Swiss National Hip & Knee Joint Registry | https://www.siris-implant.ch/ |

Brief history of participating registries

We invited all registry members of the International Society of Arthroplasty Registries (ISAR) to participate in this study and 16 regional/national arthroplasty registries were willing and able to participate. The majority of registries have high coverage and completeness (≥ 95%) of reporting primary TKAs and almost all publish annual reports on their websites providing extensive information on demographics, surgical techniques, and quality measures (Table 2).

| Registry | Established | Reported primary TKA with OA (2010–2020) | Cover-age a (%) | Completeness b | Publish annual report | |

| (%) | Year | |||||

| SAR | 1975 | 136,009 | 100 | 96–98 | 2010–2020 | Yes |

| FAR | 1980 | 94,803 | 100 | 98 | 2003–2020 | Yes |

| NAR c | 1987 | 47,584 | 100 | 97 | 2008–2020 | Yes |

| DKR | 1997 | 78,948 | 100 | 97 | 2020 | Yes |

| NZJR | 1998 | 77,305 | 100 | > 95 | 2022 | Yes |

| AOANJRR | 1999 | 527,566 | 100 | 99 | 2022 | Yes |

| KP | 2001 | 145,078 | 100 | > 90 | 2021 | Yes |

| RAR | 2001 | 33,105 | 99 | 98 | 2021 | Biannual |

| NJR | 2002 | 900,715 | 94 | > 95 | 2022 | Yes |

| LROI | 2007 | 241,306 | 100 | 95–99 | 2021 | Yes |

| AJRR d | 2009 | 952,162 | na | na | na | Yes |

| EPRD e | 2010 | 269,968 | na | na | na | Yes |

| PABZ | 2010 | 5,901 | 100 | 100 | 2011–2020 | Every 2–3 years |

| JointCare f | 2012 | 1,308 | 12 | 16 | 2016–2020 | No |

| PATN | 2012 | 115,803 | 100 | > 98 | 2020 | Yes |

| SIRIS | 2016 | 3,167 | 100 | 95 | 2016–2020 | Every 2–3 years |

| na = not available. | ||||||

| a Coverage refers to the proportion (%) of hospitals/departments contributing to registration in the national/regional register out of the total number of hospitals/departments performing knee procedures in the country/region. | ||||||

| b Completeness refers to the proportion (%) of knee operations registered in the register out of the total number performed in the country/region. | ||||||

| c NAR established with registration of hip arthroplasty in 1987, but started registration of knee and other joint arthroplasties in 1994. | ||||||

| d AJRR does not have data on coverage or completeness due to the lack of centralized healthcare and market structure. NB: Data reported from AJRR (USA) does not include that of KP (USA) data. | ||||||

| e Registry was started in 2010 and enrolment started (November) 2012. Since 2019 national completeness is > 70 %. | ||||||

| f JointCare established as an organization in 2012, but the registry started in 2015. There is no mandatory reporting of arthroplasties in South Africa. Coverage and completeness are best estimates. JointCare comprises a network of surgeons in private practice and coverage is restricted to primary surgeries. The JointCare captures revisions only when reported by a patient in follow-up correspondence. The operative data pertaining to the revision surgery itself is not captured. | ||||||

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

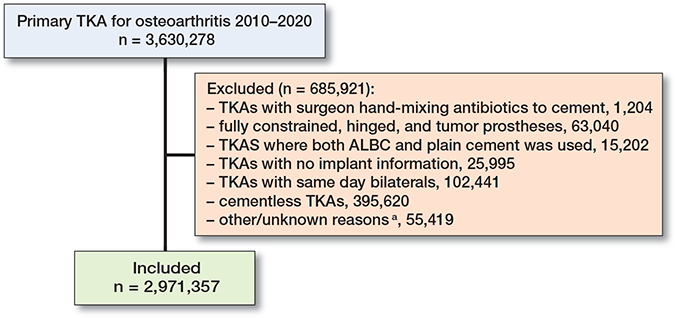

To ensure a homogeneous study population, we included only cemented (both fully and hybrid) TKAs in patients with OA as the underlying diagnosis. Tumor prostheses (segmental), hinged, fully constrained prostheses, as well as same-day bilateral primary TKA procedures were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. a Excluded TKAs with insufficient data to determine whether inclusion criteria are met.

Data extraction

We used a distributed health data network that does not require centralized data storage of individual patient-level data [14]. The NAR was the coordinating center, and, in collaboration with KP, created and sent a data-sharing template to each participating registry for reporting of aggregate information for specifically defined data elements. Each participating registry identified the eligible study sample from their dataset and reported information on patient characteristics (age, sex, BMI, and ASA class), surgical and implant characteristics, ALBC attributes, and SAP using the data-sharing template provided, which was then sent back to the NAR to compile.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions, were used. Demographic and surgical data on sex, age, ASA classification, BMI, type of fixation, patella usage, type of bone cement brands, year of procedure, cement viscosity and type of antibiotics in the cement, and the choice of SAP agent, the dose (single dose vs. multiple doses) and the duration (0–24, 24–48, > 48 hours) of SAP were described.

Ethics, data sharing, funding, and disclosures

NAR was the initiator and coordinating center for this study. Thus, ethical approval of the study was obtained primarily from the Regional Committee for Research Ethics in Western Norway (REK Vest) (registration number 2021/319783/REK Vest, dated November 24, 2021). In addition, ethical approval was obtained through the ethical approval process of each registry. During this study, the corresponding author (THL) received a postdoctoral grant from the Western Norway Regional Health Authority. No external funding was received in support of this work. Thus, each participating registry used its own resource. All authors declare no conflicts of interest. Completed disclosure forms for this article following the ICMJE template are available on the article page, doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.17737

Results

We included 2,971,357 cemented or hybrid primary TKAs (Figure 1). 77% (n = 2,293,446) of TKAs were performed with ALBC (Table 3). There was wide variation in ALBC usage among participating countries ranging from 100% use in NAR (Norway) to 31% in AJRR (USA) (Table 3). Most of the TKAs with ALBC were performed on female patients, aged 65–74 years, and were fully cemented. The majority of participating registries reported information on ASA class (11 of 16 registries) and BMI (12 of 16 registries), and they reported that most of the TKAs with ALBC were performed on pre-obese or obese class I patients and on those with ASA class II (Table 4, see Appendix). Detailed demographic and surgical-related characteristics are presented in Tables 5–7 (see Supplementary data).

Trends in ALBC usage

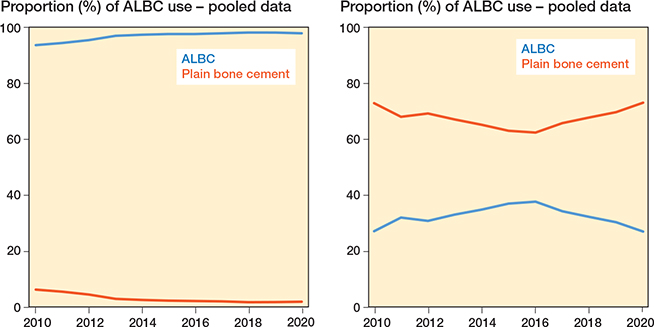

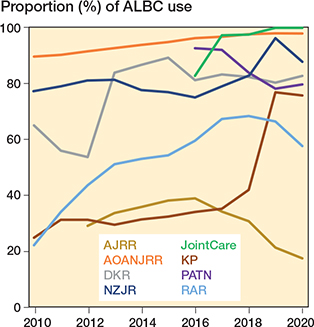

ALBC usage in primary TKA increased slightly over time internationally with pooled data from 14 of the 16 registries with ALBC use in > 50% of primary TKAs (Figure 2 left panel), but a declining trend was observed since 2016 with pooled data from registries with ALBC use in < 50% of primary TKAs (Table 3) (Figure 2 right panel). Country-wise, we also observed an increased proportion of ALBC use in primary TKA in most countries over time, particularly in DKR (Denmark), NZJR (New Zealand), RAR (Romania), and KP (USA) except for the year 2020, while a decline was observed in PATN (Italy) and AJRR (USA) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Trends in ALBC vs. plain bone cement used from 2010–2020. Left panel: pooled data from 14 of 16 participating registries with > 50% ALBC use in primary TKAs (2010–2020), see

Table 3. Right panel: pooled data from 2 of 16 participating registries with < 50% ALBC use in primary TKAs (2010–2020)

Figure 3. Trends in ALBC usage in primary TKA among 8 of 16 registries that reported ≤ 90% usage of ALBC in primary TKA for at least 1 year in the period 2010–2020.

Type of ALBC used

15 of the16 registries, excepting the AJRR (n = 241,866), provided detailed information on the type of ALBC used in TKAs. Various types of bone cement were used in the different countries. Palacos R+G (Heraeus Medical, Wehrheim, Germany) was the most common (62%) ALBC type reported followed by Refobacin Bone Cement R (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) (18%), Simplex with Tobramycin (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) (5%), CMW 2 G (DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA) (4%), Palacos MV+G (Heraeus Medical) (3%), and SmartSet GHV (DePuy) (3%). The majority of ALBC used was high viscosity (92%) and contained gentamicin (94%) or tobramycin (5%) (Table 8, see Appendix).

SAP usage

9 of 16 registries reported information on SAP use, representing 18% (530,045 of 2,971,357) of the total number of TKAs included in this study. The other registries reported that SAP use is mandatory in their respective country, but they did not record data on SAP use. 98% (517,890 of 530,045) of primary TKAs recorded in these 9 registries used SAP although there was a slight variation among reporting countries with 100% usage in NAR (Norway) to 87% in KP (USA). 2% (9,320 of 530,045) of TKA procedures were reported with plain cement and no SAP (Table 9).

| Registry | TKAs | SAP and ALBC | No SAP but ALBC | SAP and plain cement | No SAP and plain cement |

| KPa | 123,418 | 43,226 (35) | 8,237 (6.7) | 63,824 (52) | 8,131 (6.6) |

| SAR | 123,129 | 123,082 (100) | 6 (0.0) | 41(0.0) | |

| FAR | 83,469 | 83,281 (100) | 114 (0.1) | 74 (0.1) | |

| NZJR | 73,744 | 57,794 (78) | 2,379 (3.2) | 12,568 (17) | 1,003 (1.4) |

| DKR | 49,377 | 37,422 (76) | 20 (0.0) | 11,915 (24) | 20 (0.0) |

| NAR | 40,709 | 40,709 (100) | |||

| RAR | 30,816 | 17,499 (57) | 319 (1.0) | 12,833 (42) | 165 (0.5) |

| PABZ | 4,544 | 4,429 (98) | 111 (2.4) | 4 (0.1) | |

| JointCare | 839 | 734 (88) | 95 (11) | 9 (1.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Total | 530,045 | 408,170 (77) | 11,281 (2.1) | 101,268 (19) | 9,320 (1.8) |

| a KP does not prospectively capture the specific information on SAP that was needed for the study. Instead, KP retrospectively retrieved the information from its integrated electronic health record specifically for this study. | |||||

The use of ALBC in combination with SAP was a common practice in all countries recording SAP data. Of all reported primary TKA procedures performed in these countries, 77% used ALBC in combination with SAP, but the proportion varied from 100% in NAR (Norway) to 35% in the KP (USA) (Table 9).

Type, dose, and duration of SAP used

Over 50 different single SAP agents were reported. Cefazolin was the most common (32%) SAP agent used in primary TKA procedures followed by cefuroxime (27%), cloxacillin (22%), cefalotin (5%), clindamycin (4%), and vancomycin (3%) (Table 10, see Appendix). Country-wise, cefazolin was the most commonly used SAP in NZJR (New Zealand) (84%) and KP (USA) (77%), whereas cefuroxime was common in DKR (Denmark) (61%) and PABZ (Italy) (40%), cloxacillin in SAR (Sweden) (91%) and cefalotin in NAR (Norway) (70%). 5 of the 9 registries recording information on SAP use included detailed information on the dose and duration of SAP used (Table 11).

| Factor | DKR | KP | NAR | PABZ | SAR |

| Primary TKAs | 49,377 | 123,418 | 40,709 | 4,544 | 123,129 |

| TKAs with no SAP | 40 (0.1) | 16,368 (13) | 0 | 111 (2.4) | 6 (0.0) |

| Duration/dose | |||||

| 1 day 1 dose a | 3,858 (7.8) | 30,971 (25) | 1,831 (4.3) | 4,433 (98) | 788 (0.6) |

| 1 day 2 doses | 60,877 (50) | 1,412 (3.5) | 3,681 (3.0) | ||

| 1 day 3 doses | 7,098 (5.8) | 2,060 (5.1) | 97,251(79) | ||

| 1 day 4 doses | 2,065 (1.7) | 33,597 (83) | 17,874 (15) | ||

| 1 day > 1 dose | 29,961 (62) | ||||

| 2 days | 5,386 (4.4) | 959 (0.8) | |||

| 2 days or more | 544 (1.1) | ||||

| 3 days | 223 (0.2) | 354 (0.3) | |||

| Others b | 416 (0.3) | 391 (0.3) | |||

| Unknown | 14,974 (30) | 14 (0.0) | 1,809 (4.4) | 1,825 (1.6) | |

| a Preoperatively | |||||

| b Includes 1-day ≥ 5 doses; SAP administered over ≥ 4 days. | |||||

Discussion

ALBC

ALBC use is standard practice in the Scandinavian countries [1] but in other European countries and North America, the use of ALBC in primary joint arthroplasty is still variable [1,15].

In the present study, we observed that the trend for ALBC use in primary TKA is increasing over a 10-year span, with the exception of AJRR (USA). The proportion and type of ALBC used varies among countries, e.g., the AJRR (USA) (31%), had the lowest use of ALBC compared with NAR (Norway), which reported 100% use. Similar to the present study, 1 earlier study on primary TKA also reported lower utilization rates (27%) of ALBC in the USA in the period 2006–2016 [15]. The potential explanations for such variation in practice could be the lack of international consensus and the absence of high-quality evidence supporting prophylactic use of ALBC in primary TKA [7,8].

Furthermore, we observed a variation in viscosity and type of antibiotic in the ALBC used in primary TKA among countries. This could be attributed to lack of clear evidence on the impact on revision rates of bone cement brand, level of viscosity, and dose and type of antibiotics in cement. A previous study from the NAR (Norway) on hip arthroplasty has reported that the low viscosity CMW3 (DePuy) as well as the high viscosity CMW1 (DePuy) [16] were associated with higher failure rates in hip replacement. In contrast, a study on knee arthroplasty from KP (USA) reported a lower risk for all causes of revision with the use of Simplex medium-viscosity cement compared with Palacos high-viscosity cement, although no difference was observed in revision for aseptic loosening [17].

In our study, over 90% of bone cements reported contained gentamicin, although no large randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the prophylactic effect of gentamicin-loaded bone cement is available. Zhang et al. [18] in their meta-analysis found that ALBC containing gentamicin reduced deep infection rates, but no difference was found between cefuroximeloaded cement and bone cement without antibiotics. Further, a large RCT (n = 2,948) from Spain reported that the use of ALBC with erythromycin and colistin-loaded Simplex cement in TKA did not reduce the incidence of infection [19].

SAP

9 of 16 participating registries reported the use of ALBC in combination with SAP as common practice, representing 13% of total TKAs included in our study. However, the type of antibiotic agent used, duration, and doses varied among countries. A possible explanation could be attributed to lack of consensus guidelines and/or a disparate range of recommendations for SAP use in total joint arthroplasties [20]. Further, the observed variation in choice of SAP could also be attributed to regional differences in the most prevalent pathogens, including risk of Clostridium difficile infection and resistance patterns and thereby different SAP is recommended [21]. In our study, the first-generation cephalosporin cefazolin was the most common (32%) SAP agent used in primary TKA followed by the second-generation cephalosporin cefuroxime (27%). In line with our findings, a recent international survey study on guidelines for SAP use reported that 10 of 17 (59%) guidelines from arthroplasty societies suggested first-generation cephalosporin as the SAP agent of choice [20].

In our study, we observed a variation regarding the dose/duration of SAP used among participating countries ranging from 1-day 1 dose (preoperative) as standard practice in Bolzano, Italy to 1-day 4 doses in Norway. In 2017, however, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection and recommended a single dose of perioperative antibiotic prophylactic without subsequent postoperative dosing [22] and this recommendation was based on first- and second-generation cephalosporins [22]. An earlier register-based study on hip arthroplasty from Norway reported that patients who received a 1-day 1, 2, or 3 doses SAP had a 3–7 times higher rate of revision due to infection than those with 1-day 4 doses SAP [23]. Thus, a multiple-dose (4 times in a single day) regime is currently standard practice in Norway. Conversely, a recent cohort study from the Dutch Arthroplasty Register found a similar risk of revision for infection following primary hip and knee arthroplasty with single- versus multiple-dose of SAP [12]. Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis was also unable to demonstrate the efficacy of postoperative SAP in reducing the rate of PJI [9].

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it is the first large international multi-register-based observational study describing current practice in the use of ALBC and SAP in primary TKA incorporating 16 national/regional registries over 4 continents. Collaborations among national/regional registries provide added opportunities to increase/improve generalizability of the findings and to examine variation in clinical practices and outcomes between countries [24]. Due to privacy, security, and data ownership regulation, many registries cannot share even de-identified patient-level data, although pooled analysis of individual patient data is an ideal approach [25]. However, our study managed challenges in data sharing among multiple registries with a decentralized data warehouse where each participating register shared aggregate-level data, leading to an unprecedented collaboration among 16 arthroplasty registries located in 14 different countries.

Our study has some limitations. Conclusions regarding international trends in ALBC and SAP use are limited, as the data obtained is restricted to registries that are members of ISAR. These registries may not be representative of global trends given geographical regions’ over-representation of registries from Europe and no/under-representation of registries from North America, Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Nevertheless, we believe that the data from these participating registries offers a relevant description of ALBC and/or SAP utilization trends globally. Second, the data presented herein relies on accurate coding of implants’ information and is subject to reporting error. The majority of participating registries reported high completeness (> 95%) for primary joint arthroplasty, which shows that they undergo a rigorous process of internal auditing to ensure the accuracy of the collected data. Third, there may be variation in how data regarding bone cements is recorded; registries use either barcode notes, scanning of implants’ product numbers, or just text from the surgeons. Standardization of the collection of cement information from the adhesive labels with product numbers should be recommended for all registries. Fourth, only 9 of 16 participated registries recorded information on the use of SAP and type of antibiotic, and of these, only 5 recorded further information on dosage and duration of SAP. Lack of guidelines for SAP for total joint arthroplasty or consistency in their advice among arthroplasty societies was also reported [20]. Thus, recording data on the use, type of antibiotic, dosage, and duration of SAP used is recommended. We think that by doing this, registries can easily determine whether guidelines/recommendations (if existing) are actually being followed.

Conclusion

The proportion of ALBC usage in primary TKA is increasing, but varies internationally over time, with gentamicin being the most commonly included antibiotic. Use of ALBC in combination with SAP was common practice in those registries that collected these data with the 1st generation cephalosporin cefazolin being the most common SAP agent. The type of ALBC and type and dose/duration of SAP used also varies internationally and needs national/regional consensus in practice guidelines based on high-quality evidence. As this is a descriptive study, caution needs to be taken when generalizing the findings beyond the participating countries.

Perspective

We believe that the present study contributes important knowledge on the debate concerning antibiotic use and could be a basis for future international studies, such as RCTs, to answer the question regarding the effectiveness of ALBC or different SAP treatments. Thus, further clinical studies to investigate and compare the efficacy of routine use of ALBC and SAP in primary TKA in preventing PJI are recommended.

Supplementary data

Tables 5–7 are available on the article page, doi: 10.2340/17453674.2023.17737

- Randelli P, Evola F R, Cabitza P, Polli L, Denti M, Vaienti L. Prophylactic use of antibiotic-loaded bone cement in primary total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010; 18: 181-6. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0921-y.

- Shepard J, Ward W, Milstone A, Carlson T, Frederick J, Hadhazy E, et al. Financial impact of surgical site infections on hospitals: the hospital management perspective. JAMA Surg 2013; 148: 907-14. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2246.

- Dyrhovden G S, Lygre S H L, Badawy M, Gothesen O, Furnes O. Have the causes of revision for total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasties changed during the past two decades? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475: 1874-86. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5316-7.

- Bozzo A, Ekhtiari S, Madden K, Bhandari M, Ghert M, Khanna V, et al. Incidence and predictors of prosthetic joint infection following primary total knee arthroplasty: a 15-year population-based cohort study. J Arthroplasty 2022; 37: 367-72.e361. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.10.006.

- Buchholz H, Elson R, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkamper H, Rottger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1981; 63: 342-53. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B3.7021561.

- Buchholz H W, Engelbrecht H. [Depot effects of various antibiotics mixed with Palacos resins]. Chirurg 1970; 41: 511-15.

- Ekhtiari S, Wood T, Mundi R, Axelrod D, Khanna V, Adili A, et al. Antibiotic cement in arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cureus 2020; 12: e7893. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7893.

- Saidahmed A, Sarraj M, Ekhtiari S, Mundi R, Tushinski D, Wood T J, et al. Local antibiotics in primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021; 31: 669-81. doi: 10.1007/s00590-020-02809-w.

- Thornley P, Evaniew N, Riediger M, Winemaker M, Bhandari M, Ghert M. Postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ Open 2015; 3: E338-43. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150012.

- Morris A M, Gollish J. Arthroplasty and postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis. CMAJ 2016; 188: 243-4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150429.

- de Beer J, Petruccelli D, Rotstein C, Weening B, Royston K, Winemaker M. Antibiotic prophylaxis for total joint replacement surgery: results of a survey of Canadian orthopedic surgeons. Can J Surg 2009; 52: E229-34.

- Veltman E S, Lenguerrand E, Moojen D J F, Whitehouse M R, Nelissen R G, Blom A W, et al. Similar risk of complete revision for infection with single-dose versus multiple-dose antibiotic prophylaxis in primary arthroplasty of the hip and knee: results of an observational cohort study in the Dutch Arthroplasty Register in 242,179 patients. Acta Orthop 2020; 91: 794-800. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1794096.

- Von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, Pocock S J, Gøtzsche P C, Vandenbroucke J P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X.

- Cafri G, Banerjee S, Sedrakyan A, Paxton L, Furnes O, Graves S, et al. Meta-analysis of survival curve data using distributed health data networks: application to hip arthroplasty studies of the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries. Res Synth Methods 2015; 6: 347-56. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1159.

- Chan J J, Robinson J, Poeran J, Huang H-H, Moucha C S, Chen D D. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement in primary total knee arthroplasty: utilization patterns and impact on complications using a national database. J Arthroplasty 2019; 34: S188-S194.e181. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.03.006.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L, Engesaeter L, Vollset S. The type of cement and failure of total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 832-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b6.12776.

- Wyatt R W B, Chang R N, Royse K E, Paxton E W, Namba R S, Prentice H A. The association between cement viscosity and revision risk after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2021; 36(6):1987-94. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.01.052.

- Zhang J, Zhang X Y, Jiang F L, Wu Y P, Yang B B, Liu Z Y, et al. Antibiotic-impregnated bone cement for preventing infection in patients receiving primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2019; 98. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018068.

- Hinarejos P, Guirro P, Leal J, Montserrat F, Pelfort X, Sorli M, et al. The use of erythromycin and colistin-loaded cement in total knee arthroplasty does not reduce the incidence of infection: a prospective randomized study in 3000 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95: 769-74. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00901. PMID: 23636182.

- Parsons T, French J, Oshima T, Figueroa F, Neri T, Klasan A, et al. International survey of practice for prophylactic systemic antibiotic therapy in hip and knee arthroplasty. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022; 11: 1669. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111669.

- Babu S, Al-Obaidi B, Jardine A, Jonas S, Al-Hadithy N, Satish V. A comparative study of 5 different antibiotic prophylaxis regimes in 4500 total knee replacements. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020; 11: 108-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.12.003.

- Berrios-Torres S I, Umscheid C A, Bratzler D W, Leas B, Stone E C, Kelz R R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 784-91. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904.

- Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Havelin L I. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0–14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74: 644-51. doi: 10.1080/00016470310018135.

- Havelin L I, Fenstad A M, Salomonsson R, Mehnert F, Furnes O, Overgaard S, et al. The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association: a unique collaboration between 3 national hip arthroplasty registries with 280,201 THRs. Acta Orthop 2009; 80: 393-401. doi: 10.3109/17453670903039544.

- Sedrakyan A, Paxton E, Graves S, Love R, Marinac-Dabic D. National and international postmarket research and surveillance implementation: achievements of the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries initiative. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96: 1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00739.

Appendix

| Variable | AJRR | AOANJRR | DKR | EPRD | FAR | JointCare | KP | LROI | NAR |

| TKA with ALBC | 241,866 | 393,897 | 37,442 | 139,673 | 83,395 | 829 | 51,463 | 195,155 | 40,709 |

| Female sexa | 145,418 (60) | 226,436 (58) | 23,259 (62) | 92,275 (66) | 54,187 (65) | 551 (67) | 31,270 (61) | 125,841 (65) | 25,242 (62) |

| Age groupb | |||||||||

| < 55 | 21,259 (8.8) | 23,406 (5.9) | 2565 (6.8) | 10,013 (7.2) | 5,318 (6.4) | 67 (8.1) | 3,323 (6.5) | 12,502 (6.4) | 5,599 (14) |

| 55–64 | 70,351 (29) | 100,317 (26) | 7,940 (21) | 33,797 (24) | 20,946 (25) | 249 (30) | 15,160 (30) | 48,770 (25) | 8,038 (20 |

| 65–74 | 96,199 (40) | 160,880 (41) | 15,235 (41) | 46,879 (34) | 31,885 (38) | 327 (39) | 21,323 (41) | 79,073 (41) | 15,194 (37) |

| ≥ 75 | 54,057 (22) | 109,294 (28) | 11,702 (31) | 48,984 (35) | 25,246 (30) | 186 (22) | 11,658 (23) | 54,649 (28) | 11,878 (29) |

| ASA class | na | na | na | ||||||

| I | 15,606 (4.0) | 2,056 (1.5) | 3,370 (4.0) | 655 (1.3) | 28,422 (15) | 3,737 (9.2) | |||

| II | 162,375 (41) | 7,898 (5.6) | 25,392 (30) | 30,790 (60) | 131,168 (67) | 27,457 (67) | |||

| III | 121,261 (31) | 4,493 (3.2) | 19,704 (24) | 18,677 (36) | 34,310 (18) | 8,539 (21) | |||

| IV–V | 3,493 (1.0) | 75 (0.1) | 473 (0.6) | 305 (0.6) | 449 (0.2) | 71 (0.2) | |||

| Missing | 91,162 (23) | 125,208 (90) | 34456 (41) | 1,036 (2.0) | 806 (0.4) | 905 (2.2) | |||

| BMI categoryc | na | ||||||||

| Underweight | 270 (0.3) | 441 (0.2) | 105 (0.3) | 175 (0.1) | 48 (0.1) | 4 (0.5) | 77 (0.1) | 195 (0.1) | |

| Normal | 8,871 (9.8) | 24,479 (10) | 6,374 (17) | 12,610 (9.0) | 6,317 (7.6) | 95 (12) | 5,736 (11.1) | 22,222 (11.4) | |

| Pre-obese | 24,250 (27) | 72,070 (31) | 12,691 (34) | 31,072 (22) | 17,444 (21) | 219 (26) | 16,039 (31) | 57,431 (29) | |

| Obese class 1 | 26,212 (29) | 71,974 (31) | 8,309 (22) | 26,413 (19) | 14,740 (18) | 253(31) | 16,319 (32) | 40,270 (21) | |

| Obese class 2 | 18,603 (21) | 40,592 (17) | 3,532 (9.4) | 12,885 (9.2) | 6,312 (7.6) | 150 (18) | 9,742 (18.9) | 15,388 (7.9) | |

| Obese class 3 | 12,107 (13) | 25,550 (11) | 1,577 (4.2) | 7,216 (5.2) | 1,650 (2.0) | 108 (13) | 3,517 (6.8) | 5,494 (2.8) | |

| Missing | 151,553 (63) | 158,791 (40) | 4,853 (13) | 49,302 (35) | 36,884 (44) | 33 (0.1) | 54,155 (28) | ||

| Variable | NJR | NZJR | PABZ | PATN | RAR | SAR | SIRIS | Total | |

| TKA with ALBC | 810,644 | 60,173 | 4,540 | 970 | 17,818 | 123,088 | 91,784 | 2,293,446 | |

| Female sex | 463,557 (57) | 31,032 (52) | 2,925 (64.4) | 561 (58) | 13,822 (78) | 70,452 (57) | 55,210 (60) | 1,361,082 (59) | |

| Age group b | |||||||||

| < 55 | 46,596 (5.7) | 4,365 (7.3) | 120 (2.6) | 42 (4.3) | 809 (4.5) | 6,287 (5.1) | 6,055 (6.6) | 148,326 (6.5) | |

| 55–64 | 181,159 (22) | 17,054 (28) | 659 (15) | 178 (18) | 5,211 (29) | 28,738 (23) | 21,925 (24) | 560,492 (24) | |

| 65–74 | 325,568 (40) | 24,098 (40) | 1,934 (43) | 413 (43) | 8,836 (50) | 49,937 (41) | 34,089 (37) | 911,870 (40) | |

| ≥ 75 | 257,321 (32) | 14,656 (24) | 1,827 (40) | 337 (35) | 2,313 (17) | 38,123 (31) | 29,649 (32) | 906,910 (40) | |

| ASA class | na | ||||||||

| I | 68,137 (8.4) | 6,151 (10) | 397 (8.7) | 8 (0.8) | 20,918 (17) | 6,312 (6.9) | 155,769 (6.8) | ||

| II | 595,982 (74) | 38,104 (63) | 2,285 (50) | 180 (19) | 80,930 (66) | 43,391 (47) | 1,145,952 (50) | ||

| III | 144,145 (18) | 15,101 (25) | 288 (6.3) | 27 (2.8) | 20,832 (16.9) | 19,611 (21.4) | 406,988 (18) | ||

| IV–V | 2,380(0.3) | 102 (0.3) | 2 (0.0) | 235 (0.2) | 264 (0.3) | 7,953 (0.3) | |||

| Missing | 611 (1.0) | 1,568 (35) | 755 (78) | 173 (0.1) | 22,206 (24) | 278,886 (12) | |||

| BMI category c | na | na | na | ||||||

| Underweight | 950(0.1) | 67 (0.1) | 181 (0.1) | 298 (0.3) | 2,811 (0.1) | ||||

| Normal | 58,700 (7.2) | 4,343 (7.2) | 22,203 (18.0) | 13,150 (14.3) | 185,100 (8.1) | ||||

| Pre-obese | 207,996 (26) | 13,628 (23) | 53,221 (43.2) | 24,457 (26.6) | 530,518 (23) | ||||

| Obese class 1 | 201,963 (25) | 12,639 (21) | 34,747 (28.2) | 15,778 (17.2) | 469,617 (21) | ||||

| Obese class 2 | 104,287 (13) | 7,100 (12) | 10,440 (8.5) | 6,596 (7.2) | 235,627 (10) | ||||

| Obese class 3 | 44,072 (5.4) | 4,051 (6.7) | 2,113 (1.7) | 2,946 (3.2) | 110,401 (4.8) | ||||

| Missing | 192,676 (24) | 18,345 (31) | 183 (0.1) | 28,559 (31.1) | 684,628 (30) | ||||

| Missing cases: a AJRR (n = 333); LROI (n = 228). b LROI (n = 161); SAR (n = 3); SIRIS (n = 490). c BMI categories are based on WHO classification: underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–< 25), pre-obese (25–< 30), obese class 1 (30–< 35), obese class 2 (35–< 40), and obese class 3 (≥ 40.00). na = not available. | |||||||||

| Type/name of ALBC | Company | Viscosity | Antibiotics used | Used in TKA n (% of N)a |

| Palacos R + G | Heraeus | High | Gentamicin | 1,265,765 (62) |

| Refobacin Bonecemet R | Zimmer Biomet | High | Gentamicin | 362,845 (18) |

| Simplex with Tobramycin | » | Medium/high | Tobramycin | 101,001 (5.0) |

| CMW 2 G | » | Medium | Gentamicin | 90,927 (4.4) |

| Palacos MV+G | » | Medium | Gentamicin | 55,624 (2.7) |

| SmartSet GHV | » | High | Gentamicin | 58,331 (2.8) |

| CMW 1 G | DePuy | High | Gentamicin | 24,703 (1.2) |

| Copal G+ V or C+V | » | High | Gentamicin and vancomycin or Clindamycin and vancomycin | 10,116 (0.5) |

| Simplex HV | » | High | Gentamicin | 33,463 (1.6) |

| Cemex with Gentamicin | Alere | High | Gentamicin | 8,028 (0.4) |

| Palamed G | » | Medium | Gentamicin | 7,980 (0.4) |

| Refobacin Bonecemet R-3 | » | High | Gentamicin | 7,133 (0.4) |

| SmartSet GMV | » | Medium | Gentamicin | 5,015 (0.2) |

| Simplex EC | Styrker | Medium/high | Erythromycin and colistin | 4,419 (0.2) |

| Palacos (other than R + G) | » | Low/medium/high | Vancomycin and gentamicin | 4,477 (0.2) |

| Aminofix 1 | Lépine | Medium | Gentamicin | 2,796 (0.1) |

| Gentafix 1 | Teknimed | High | Gentamicin | 1,997 (0.1) |

| Hi-Fatigue G Bone Cement | Zimmer | High | Gentamicin | 1,073 (0.1) |

| Subiton G | Subiton | High | Gentamicin | 736 (0.0) |

| Versabond | Smith & Nephew | Medium | Gentamicin | 498 (0.0) |

| Smartset GMV Endurance | » | Medium | Gentamicin | 376 (0.0) |

| CMW 3 G | » | Low | Gentamicin | 352 (0.0) |

| Orthocem 1G | » | Standard/high | Gentamicin | 356 (0.0) |

| Synicem 1G | MedicalExpo | Standard | Gentamicin | 331 (0.0) |

| Rally HV | » | High | Gentamicin | 293 (0.0) |

| Refobacin Revision (Refobacin Revision-3) | » | High | Gentamicin and clindamycin | 274 (0.0) |

| Palacos LV+G | » | Low | Gentamicin | 164 (0.0) |

| Aminofix 3 | » | Low | Gentamicin | 103 (0.0) |

| Gentafix 3 | » | Low | Gentamicin | 94 (0.0) |

| Amplifix 1 | Amplitude | Medium | Gentamicin | 89 (0.0) |

| Genta C~ment 1 Bone Cement | Biomedical | High | Gentamicin | 85 (0.0) |

| Subiton Quirurgico G | » | Low | Gentamicin | 42 (0.0) |

| Biogent I | » | Standard | Gentamicin | 31 (0.0) |

| VancoGenx | » | High | Vancomycin and gentamicin | 19 (0.0) |

| MectaCem III | Medacta | Low/standard | Gentamicin | 14 (0.0) |

| Cemex Gent LV | » | Low | Gentamicin | 1 (0.0) |

| BonOs R Genta | Osartis | High | Gentamicin | 1 (0.0) |

| Other (not specified)b | 1,216 (0.1) | |||

| Unknownc | 2,360 (0.1) | |||

| a FAR and KP reported a greater number of ALBC than the number of TKAs included. This was because patients may have had more than 1 type of cement, as explained by the KP. Thus, the total denominator of ALBC (n = 2,022,371) was greater than the number of TKA with ALBC included (n = 2,020,823) (see Table 2). | ||||

| b Procedure using a mixture of different types of cement or others. Difficult to differentiate antibiotics used because it is mixed-use and will contain cement with different antibiotics. Most of the antibiotics used are gentamicin (though a small number are mixed with erythromycin, tobramycin and/or vancomycin) but insufficient information in most procedures. | ||||

| c TKA with ALBC, but missing information on name of ALBC, antibiotic loaded, and /or company/manufacturer | ||||

| Generic name | ATC code | Registry reporting SAP | Used in TKA n (% of 517,890) a |

| Cefazolin | J01DB04 | JointCare, KP, NAR, NZJR, PABZ, RAR | 165,915 (32) |

| Cefuroxime | J01DC02 | DKR, FAR, JointCare, KP, NAR, NZJR, PABZ, RAR, SAR | 139,306 (27) |

| Cloxacillin | J01CF02 | FAR, NAR, SAR | 114,240 (22) |

| Cefalotin | J01DB03 | FAR, NAR | 23,404 (4.5) |

| Clindamycin | J01FF01 | FAR, JointCare, KP, NAR, NZJR, RAR, SAR | 18,716 (3.6) |

| Vancomycin | J01XA01 | DKR, FAR, JointCare, KP, NAR, NZJR, PABZ, RAR, SAR | 13,963 (2.7) |

| Cefpirome | J01DE02 | FAR, RAR | 8,652 (1.7) |

| Gentamicin | J01GB03 | JointCare, KP, NAR, NZJR, RAR | 8,620 (1.7) |

| Ceftriaxone | J01DD04 | FAR, JointCare, KP, NZJR, PABZ, RAR | 6,106 (1.2) |

| Cefotaxime | J01DD01 | NAR, PABZ, RAR, SAR | 2,475 (0.5) |

| Dicloxacillin | J01CF01 | DKR, NAR | 1,396 (0.3) |

| Cefoperazone | J01DD12 | RAR | 1,337 (0.3) |

| Cefalosporine | J01D | RAR | 1,086 (0.2) |

| Ceftazidime | FJ01DD02 | FAR, KP, PABZ, RAR | 1,056 (0.2) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | AJ01CR02 | JointCare, RAR | 273 (0.1) |

| Oxacillin | J01CF04 | RAR | 751 (0.1) |

| Ciprofloxacin | J01MA02 | FAR, JointCare, KP, NAR, RAR, SAR | 336 (0.1) |

| Teicoplanin | J01XA02 | JointCare, PABZ, RAR | 271 (0.1) |

| Polymyxin | J01XB02 | KP | 104 (0.0) |

| Tobramycin | J01GB01 | KP | 84 (0.0) |

| Levofloxacin | J01MA12 | JointCare, KP, PABZ, RAR | 63 (0.0) |

| Piperacillin | J01CA12 | KP, RAR | 58 (0.0) |

| Cefamandole | J01DC03 | NZJR, PABZ | 54 (0.0) |

| Cefadroxil | J01DB05 | RAR | 34 (0.0) |

| Aztreonam | J01DF01 | KP | 33 (0.0) |

| Cefalexin | J01DB01 | NAR, RAR | 25 (0.0) |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | J01CR01 | RAR, | 22 (0.0) |

| Metronidazole | J01XD01 | KP, NAR | 16 (0.0) |

| Azithromycin | J01FA10 | KP | 13 (0.0) |

| Amoxicillin | J01CA04 | NZJR, RAR | 12 (0.0) |

| Ampicillin | J01CA01 | KP, NAR, PABZ, RAR | 10 (0.0) |

| Amikacin | J01GB06 | RAR | 10 (0.0) |

| Combination of 2 or more SAP used | |||

| Cefuroxime and vancomycin | FAR | 47 (0.0) | |

| Clindamycin and other (unspecified) | FAR | 19 (0.0) | |

| Cefuroxime and other (unspecified) | FAR | 18 (0.0) | |

| Cefuroxime and clindamycin | FAR | 14 (0.0) | |

| Vancomycin and other (unspecified) | FAR | 3 (0.0) | |

| Clindamycin and vancomycin | FAR | 2 (0.0) | |

| Others (n < 10)b | 78 (0.0) | ||

| Unknownc | 9,268 (1.8) | ||

| ATC = Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. | |||

| a 4% (20,627) of TKAs reported by the 9 registries did not use SAP. Besides, some registries reported use of 2 or more types of SAP per procedure. These could explain the reason why the number of SAP agents used presented here differs from the total number of TKAs from the 9 registries presented in Table 9. | |||

| b Penicillin G (J01CE01) (n = 3), cefepime (J01DE01) (n = 7), cefotetan (J01DC05) (n = 3), cefoxitin (J01DC01) (n = 7), piperacillin/tazobactam (J01CG02) (n = 7), flucloxacillin (J01CF05) (n = 8), meronem (J01DH02) (n = 4), ertapenem (J01DH03) (n = 6), imipenem/cilastatin (J01DH51) (n = 2), imipenem (J01DH56) (n = 2), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (J01EE01) (n = 9), erythromycin (J01FA01) (n = 3), clarithromycin (J01FA09) (n = 1), norfloxacin (J01MA06) (n = 1), moxifloxacin (J01MA14) (n = 1), doxycycline (J01AA02) (n = 8), linezolid (J01XX08) (n = 5), daptomycin (J01XX09) (n = 1). | |||

| c Others, but not specified or reported as unknown. | |||